Suddenly the nation is talking about black equality.

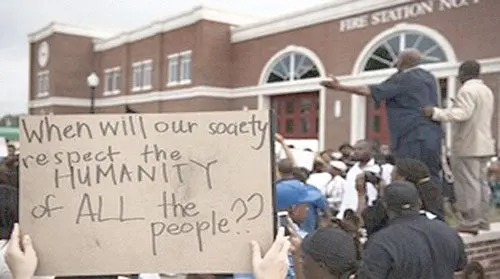

It took Molotov cocktails in Ferguson, Mo., to forcefully penetrate our slumbering racial consciousness. Ferguson has become a metaphor for race relations in the 21st century; a signifier for the convergence of poverty, segregation, police brutality and federal and civic neglect. Most importantly, the Ferguson crisis has forced the nation to re-examine the idea of Black equality.

Make no mistake: Notions of Black equality travel through both historical and contemporary terrain that Americans are loath to discuss. Black equality is more specific, and ironically more universal, than the generic advocacy of “racial equality.”

Anti-Black racism in America is essential to understanding the roots of the Ferguson tragedy. From this perspective, Michael Brown is simply the latest victim in a much larger racial drama.

Black enslavement created this nation and in the process reinvented global capitalism. Our national heritage includes deep and enduring patterns of institutional racism that haunt us all even as some deny its very existence. Contrary to popular opinion, the civil rights movement did not save America’s soul. It merely ushered us into a new, uneasy phase of national race relations, where transcendent Black achievement co-exists alongside staggering Black disadvantage.

Black equality is always the unspoken elephant in the room in discussions of race and democracy. This is not to ignore the issues of class on obvious display during this upheaval, since the Black poverty rate, which stands at 28 percent, should be a national crisis. Almost 40 percent of Black children live below the poverty line. To be #PBB (Poor, Black and Broke) is part of the urban Black experience and is quickly becoming a suburban and rural phenomenon as well.

The search for Black equality in the age of Obama has been obscured, even hampered, by the fetishization of the transcendent achievement of Black elites, exemplified by the president’s own iconography. Not to blame President Obama or suggest that Black excellence be ignored—it can’t and it shouldn’t. But so long as we remain idly obsessed with the purchasing power and bling of rappers, movie stars and celebrities, we ignore our collective responsibility to the Black poor and working class who make up the bulk of Black America.

The measuring stick for American democracy now, as always, is how far a nation based in racial slavery, subjugation and caste has come on the issue of Black equality. Ending racial segregation, unemployment, poverty and mass incarceration in the Black community is a universal struggle. If they are defeated here, poverty and inequality can be eradicated nationally. Conversely, so long as they thrive in the Black community, the rest of society will continue to be plagued by massive inequality, too.

Black equality in reality would mean that African American success and failure would be closely aligned with that of White counterparts. This would lift millions out of poverty, transform public education, employ countless numbers of the unemployed and release thousands from the criminal-justice system.

Perhaps most importantly, Black equality would end unequal treatment that African Americans receive from institutions and their representatives. Michael Brown’s death is the tip of the iceberg on this score. Access to health care, voting rights, good jobs and schools, local city services, and environmentally safe, clean neighborhoods are all impacted not just by racial bias but also by anti-Black racism.

Diversity, multiculturalism and racial equality are not enough, even as these terms all flow, ironically, from the Black freedom struggle that inspired so many other groups (including labor, farmworkers, Latinos and women) seeking justice.

Black equality holds the key not only to democracy’s future but also to our very humanity. It’s the enduring national yardstick and thermometer. We can judge the treatment of immigrants, gays and lesbians, poor people, the physically challenged, and the marginalized by the identity that has served as America’s literal and figurative bête noire.

Ferguson offered powerful glimpses of the faces whose successes, failures and achievements offer the best measure of Black equality.

People are hungry for the truth. America’s racial Pandora’s Box has been opened, and whether or not we are courageous enough to admit it, there are many more potential Fergusons awaiting us if we don’t get our own house in order. Like all moments of crisis, Ferguson offers the nation an important opportunity: to finally dedicate the full weight of our national political, economic and intellectual resources not just to advancing black equality but to actually achieving it.

-Peniel E. Joseph, a contributing editor at The Root, is founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and a professor of history at Tufts University. – The Root/ New America Media

Leave a Reply