DEARBORN — On his gravestone, Arab poet Al-Ma’arri wrote, “This is what my father gave me, and I did not give it to anybody.”

Even if you haven’t heard of the poet, you can learn about his life from the stone marking his death. He lived a rough life and did not have children.

University of Michigan-Dearborn political science professor Ron Stockton is aware of the history that can be retrieved from cemeteries. To demonstrate the complexity of the Muslim community, he and his students gathered hundreds of pictures of Muslims’ tombstones in Southeast Michigan. Forty of the photos are displayed in a gallery at the Henry Ford Centennial Library in Dearborn.

“I’m Ron Stockton and I like graveyards,” the professor said in a lecture on the exhibit on Tuesday.

The project kicked off after Stockton started “Graveyards 101”, a one credit hour class on cemeteries. He said the first time the class was offered, no Muslim students showed up. By the third and last time, there were five Muslims in the classroom.

“I said we should find every place in Southeast Michigan where Muslims are buried,” Stockton recalled telling his students. “They thought this was a wonderful idea.”

The political science professor and his students set off locating, visiting and photographing Muslim plots in Metro Detroit cemeteries.

“A gravestone is not about death; it’s about life,” Stockton said. “It is your last chance of telling people who you were, what was important to you and how you want to be remembered.”

The headstones reflect the diversity of Muslims in Southeast Michigan. The simple photos of tombs can be used as anthropological means to study the culture, nationality and history of Muslim individuals who lived and died in Metro Detroit.

Stockton said if you live in southeast Dearborn, you would think that all Muslims are Arab and mostly Lebanese Shi’a, but the tombs of Muslims in the area demonstrate a different reality.

The gallery shows that Muslims buried in Metro Detroit have come from all corners of the globe. Husein Chao Fong Pai was a Chinese American Muslim. Jubril Masha was born in Lagos, Nigeria. Ali Gacaferit came to the United States from Albania in Eastern Europe and died in 1988 at age 37.

“We counted people from 20 different countries, and each country, each culture, each religious sub-category has its own style of graveyard and gravestone,” Stockton said.

He added that the differences show that the tombs are Muslims’ graves not Islamic graves, in that religion is not the defining aspect of the tomb or the person buried in it.

“You find as much variety in the gravestones as much as you find in individuals,” he said. “In the gravestones, you find art, you find history, you find politics, you find joy, you find tragedy, you find poetry, you find religion. It’s just amazing to go to a graveyard and look at it systematically.”

Some of the graves featured in the exhibit are modest stone plaques with names and dates. Others are engraved with elaborate depictions of Islamic monuments, religious figures, logos of social clubs or portraits of the dead.

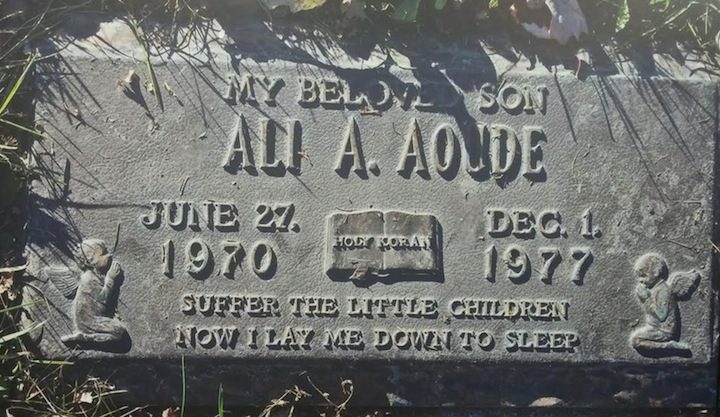

The tombstone of 7-year-old Ali, who died in 1977, features two kneeling angels, which typically appear on Christian monuments. “Suffer the little children,” reads a line from the Bible at the bottom of the stone. But in the center, there is an engraving of an open book that says “Holy Koran.”

Stockton explained that Muslim families in the United States have started borrowing tomb trends and burial traditions from their Christian neighbors.

Tombs also tell stories of Muslims’ service in the U.S. military. Some headstones show the deceased’s years of service or feature their portraits in military uniforms. Meriem Semtner’s headstone identify her as a “beloved wife, mother and daughter.” She lived from 1952 to 2000. But before introducing her as a family woman, the tomb highlights her service in the U.S. Navy right below her name.

Stockton said he is an academic who wrote a book about the Muslim community and lived among Muslims for decades.

“But then I realized there is no such a thing as the Muslim community,” he added. “It’s a mosaic of communities. There’s a whole bunch of Muslim communities and they’re very different. They come from different histories.”

The Black Sea peninsula of Crimea made international headlines last year after Russia annexed it from Ukraine. Several tombs of Muslim Tatars from the contested peninsula are featured in the exhibit.

Statements on the tombstones vary from messages to the deceased by his or her family to poetry verses to prayer requests from the dead to the living.

The gallery features many misspelled names on gravestones. Stockton suspected that the misspellings are the product of the poor English of the departed ones’ families.

Stockton said the graves emphasize the place of origin of dead Muslims because immigrants never get over the fact that they had to leave their homelands. He added that even immigrants who assimilate and identify with this country still feel a sense of loss.

“It’s called the silent sorrow of immigration,” he said.

Among the photos exhibited at the library is one of the of graves of Hussein Karoub, the first imam in Metro Detroit. He died in 1973. Karoub is identified on his headstone as the leader of Islam in North America.

Mike Karoub, the imam’s grandson, said he was surprised to see his grandfather featured in the exhibit.

“I was absolutely delighted to see the contributions of my family noticed,” he said.

Leave a Reply