|

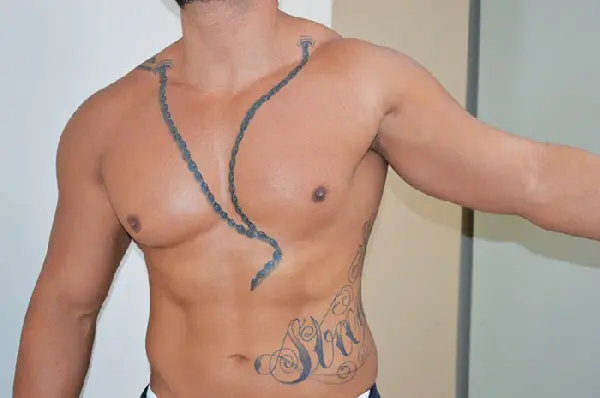

| Hussein’s rosary tattoo. |

DEARBORN — As she waited in anticipation for the announcement, Shadia Amen recalled her 15 years of hard work. A nurse’s aide at a Dearborn public school, she was about to find out if her dedication would result in an Impact Award, which were granted to 10 members of Dearborn’s non-teaching staff last month.

Amen was among the nominees, but she differed from the others in a key respect.

Days earlier, she’d debated whether she should wear long sleeves to the Green Tie dinner in order to hide the massive tattoos embezzled on her arms, shoulders and back. She didn’t want to offend those who would applaud if her name was called.

But when Amen showed up, her adorned skin gleamed proudly among the crowd.

“I got nothing to hide,” she said.

About half of her body is covered in tattoos. An angel glares at those who get a glimpse of her back, a candle-holding cedar tree adorns her forearm and red and blue stars and stripes embrace the notable calligraphic name of Allah.

The manifestation of a treasured culture and patriotism for the homeland through the radical art of tattooing marks the skin of countless Arab American youth. This blending of a bombastic western craft with a meticulous oriental design unveils a unique way in which new generation Arabs showcase their culturally diverse identities.

Although tattooing is largely condemned in Middle Eastern cultures and Islam, Amen said she sees her body as a canvas on which she can decoratively display memories and honor loved ones. It can also serve as daily reminders of lessons learned.

Her largest tattoo, a pink-haired woman portrayed as a fallen angel, looks over her shoulder and covers her entire back. To her, it represents a dark period in her life she chose to leave in the past.

“While they’re not the happiest moments in my life, they still happened,” she said. “They’re on my back because it’s behind me.”

She explained that the cedar tree with red roots on her forearm tells the story of countless who died for her country of Lebanon. The tree holds two candles, signifying the country’s resilience in times of war. Tiny figures stand behind the tree, representing the diverse community striving to coexist.

Even the three tiny green, yellow and black birds hold great meaning to Amen. A famous lyric— “Everything’s gonna be all right”— from Bob Marley’s song “Three Little Birds” also adorns her skin.

Amen said her mother saw the first of her 11 tattoos, on her lower back, when she was in her early 20s and bent over, giving her new-born son a bath.

|

| Shadia Amen. |

“You’re stupid,” Amen recalled her mother saying.

That was it.

The comment may come as a surprise to many who have experienced negative attitudes toward tattoos in Arab households. However, Amen said her parents have lived all or most of their lives in the United States and have grown accustomed to more liberal views.

When she visits her grandmother, however, Amen often wears sweaters and hoodies. Her clothes have to be concealing enough not to provoke her grandmother.

At her job working with children, Amen said she is sometimes met with reluctance, but overall enjoys acceptance from coworkers and the children’s parents.

The rift in Amen’s world, where one side welcomes the expression for flamboyant individuality, while the other respects modesty and conservatism, is a reality of many local young Arab Americans who feel caught in a “purgatory of values” – somewhere between still being respectable and “Americanized.”

Amen’s brother Bilal, director of operations at Hype Athletics, shares a similar story. Bilal Amen, who has more of his skin inked than his sister, sees his tattoos as significant pieces of his life encapsulated into art. But throughout the years, his tattoos have provided him with plenty of opportunities to strike up conversations with others about his culture and religion.

His first tattoos inscribed the names of family members on his left arm. His right arm features the sword of Imam Ali, a prominent historical Muslim figure. Elsewhere on his body, calligraphied verses from the Quran and supplications shroud Bilal’s body with the holy words of God.

One of his 17 tattoos, a large cedar tree of the Lebanese flag with roots that appear to be digging into his back, illustrates his country’s strength, especially after war. He decided to get that tattoo following the Lebanese-Israeli conflict in 2006.

At the end of fruitful dialogue about his tattoos, he said some who might have initially mistaken him for a “biker or gangster” come away with an entirely different perspective on what Arab and Muslim Americans could look like.

“You want to give people something to read when they look at your dead body?” he recalled his father sarcastically telling him.

“Why not, they’ll enjoy it,” he replied.

From young people at the athletic center to his neighbors at the mosque, Amen said he regularly spots a handful of fellow tattooed Arabs on any given day. He added that tattoos are becoming a norm in Arab American communities.

Another tattooed Arab, Hussein, who wished not to reveal his last name, said he fears he might be ostracized by his neighbors for the ink all over his body.

|

| Bilal Amen. |

Hussein’s passion for tattoos led to a torso covered in ink, but living in a community of traditional immigrants, he makes sure the ink does not show under a T-shirt.

Hussein said he made sure his tattoos could be easily covered when he got them. He considers them private reflections of himself and does not seek to exhibit them.

A massive rosary adorns his torso. The name of his son, Ali, rests on his right shoulder, as if reserving a permanent seat to for him to carry.

Hussein recalled his father saying he looked like a “thug” when he discovered the tattoos. He said he understands why tattoos are not for everybody, adding that the negative attributes about permanent ink stems from a tendency for some to choose what to get too hastily, leading to more tattoos and a cluttered “canvas.”

“It’s about you,” he said.

Hussein urged those who want to get inked to find the right artist for their style, one who practices safe and clean tattooing.

Happy, a Wyandotte-based tattoo artist who has been etching his artwork on Shadia and Bilal Amen for 12 years, said many local Arabs come to him to get tattoos – many times to escape neighbors’ gossip.

“There are a lot of closeted Shadias,” he said, adding that many women wearing hijabs harbor tattoos, unknown to their families and friends.

Over the buzzing of his tattoo gun, Happy said that a few decades ago, only those on the fringes of society were seen with tattoos. Today, he is confident in engraving ever-lasting cedar trees, Imam Ali swords and the peculiar lines and curves that form the name of Allah.

“They call it Americanized; I just call it living,” he chuckled.

Happy said Arab Americans often submit to pressure from others who encourage them to get religious tattoos or sometimes something completely different from the design they’ve wanted for months or years.

“Religious tattoos are a guide for some people to fall back on,” he said.

But the expression of one’s self through this art form, incorporating Eastern patterns and Arabic calligraphy, is an outlet for many to set themselves apart, while maintaining their heritage.

“It’s a personal thing,” Happy said. “You can create a personal image that’s strictly for you. You were not born like anybody else, so what better way of showing your uniqueness?”

Bashar Alaeddine, a photographer in Jordan, said he was intrigued with tattoos and the poetry of the Arabic language at a young age. Now, Alaeddine is working on a photo documentary project called “Arab Ink”, capturing images of symbols, patterns and artful writing that reveal testimonies from tattooed young Arab men and women in his country.

“Tattoos have emerged as a new medium, not only for the art of Arabic calligraphy, but for a new generation of Arab youth who are searching for a means of defining their identity,” Alaeddine said.

He said while Western media relegates the Middle East to a “religion-centric war zone”, the region’s youth share a unified voice of language and culture that extends beyond religion— one the press fails to recognize.

“Each photograph…reveals a more complex and diverse people and culture, with a singular means of expressing their identity through the Arabic language,” Alaeddine said.

Leave a Reply