|

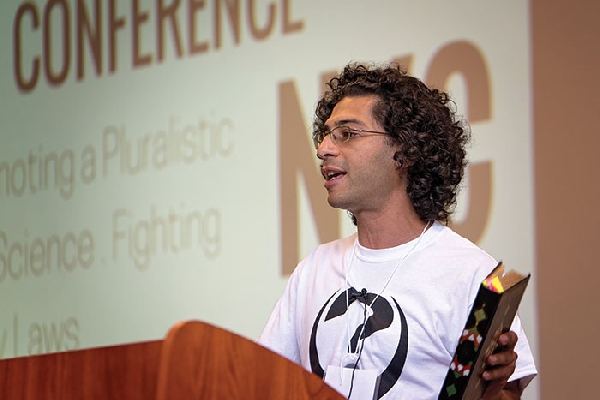

| Ibrahim Abdallah PHOTO: Alishba Zarmeen/Purple Canvas Photography Toronto |

NEW YORK — “Take your shoes off and come in, brother,” said a warm, reverent man as he gestured past the gates of the mosque on 33rd Street.

Cab drivers, pharmacists, teenagers and mothers, among others, had just risen from their last kneeling in prayer. On this Friday night, June 17, Ramadan permeated the avenues and alleyways of Astoria, New York, known as “Little Egypt.”

Inside, five Egyptian elders squeezed into the cramped office of Ahmed Jamil, director of the mosque.

“We don’t apologize for anything; we are proud here,” Jamil said, denouncing the slightest association with the ideology of the man who had shot up a gay nightclub in Miami on the first day of Ramadan.

Despite rampant bigotry endured by many Muslims nationwide, Jamil explained that in his town, the Egyptian, Chinese, Latino and White residents face similar struggles.

“You know the commissioner? I have his number on speed dial,” he said, boasting of the mosque’s relationship with the city.

This town’s Muslims have little to worry about.

A few train stops from Midtown, in the city of blaring lights, honking horns and skyscrapers, there are few places in the world where as many diverse ideas and thoughts are crammed.

On Saturday, June 18, New York City’s cops could be spotted from almost every direction, but a handful of officers, parked outside the Hotel Roosevelt, were there for more than casual policing.

While Little Egypt’s Muslims reveled in Ramadan’s spirit the previous night, Ali Rizvi, a Pakistani Canadian Muslim visiting New York to give a lecture about a book he authored, received a peculiar message on Facebook from an unknown account.

It was a map of Manhattan.

Rizvi gives talks around the country and this was not the first time he has received an anonymous message indicating his location.

His upcoming book is titled “The Atheist Muslim.”

Rizvi and the hotel did not want to leave anything to chance. New York’s finest were on guard, in case of any threat on the venue.

The hotel was packed with dozens of people who’d traveled from several states to hear Rizvi and other speakers in the middle of Manhattan. The self-proclaimed Muslim Atheist and other self-described free-thinking and ex-Muslims there had more to fear than Astoria’s devout Muslims.

At the hotel, Ibrahim Abdullah, an Egyptian American, held up a Quran to a crowd.

“This is Islam,” Abdullah said with a fiery passion.

He explained that if people were to follow the holy book as a guide to life, they are granted eternal delight in paradise after death. If one does not embrace the text’s instructions – eternal hellfire.

This notion has made many Muslims across the globe uncomfortable, as numerous adherents are beginning to question the infallible teachings of Islam or even shed their faith entirely.

About 23 percent of Americans say they have no religion, according to the Pew Research Center. Other organizations say there are far more.

Muslimish

Many Muslims call themselves progressives, skeptics or atheists.

Some call themselves Muslimish.

That is the name of the organization that hosted the conference in Manhattan. Abdullah, the group’s founder and New York organizer, said Muslimish exists to allow space for unabashed dialogue about Islam and its teachings.

The group has a dozen chapters nationwide, including in Michigan, Pennsylvania and New York.

Abdullah added that social and political reforms in the Middle East related to religion can occur only when the heavenly origins of the Quran are freely discussed.

Questioning the faith can lead to a severe punishment in many Islamic countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt, according to Abdullah. He said Islam’s focus on authenticity prohibits individuals from contemplating thoughts critical of the faith.

In the U.S., freedom of speech grants Abdullah the ability to initiate dialogue about all the verses of the Quran that, he says, “contradict science, logic and 21st century ethics.”

Detroit-based Muslimish members say the majority of secular Muslims remain underground, purposefully hidden in the murky depths of an iceberg of non-religious Arabs.

Many community members, including local officials, entrepreneurs and teachers, would never dare to say they are non-believers, Jaafar, a local businessman said.

Evoking a sheikh at a sermon, Jaafar (not his real name) recited Quranic verses, only to shatter that appearance with his explanations of the texts. While many Muslims hold that the Quran supports scientific facts, Jaafar said the book is riddled with ambiguity and contradictions.

He read an example from chapter 5, verse 33, a segment regarding the punishment of infidels. To Jaafar, the text can be interpreted as preaching violence and intolerance. He acknowledged that text is often interpreted to prescribe punishment for those who have historically persecuted Muslims.

Regardless, the ambiguity of the verse is the point for Jaafar.

“There’s a billion and a half Muslims in the world and there’s almost a billion versions of Islam,” he said. “People have so much personalized the understanding of the text. It varies from one person to another; and there are leaders with followers and there are groups within groups, within groups.”

He added that Arabic is a poetic language that utilizes emotion as an integral aspect of its structure. Therefore, the Quran presents its arguments emotionally, instead of rationally.

In some Middle Eastern countries, there have been a handful of well-publicized cases of individuals being exiled, jailed or executed for blogging or posting a Facebook status opposing Islam.

But even in the U.S., atheists are considered among the least trusted groups. A 2011 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that atheists are as untrustworthy as rapists.

“Here in America, a person who can be labeled as an apostate can have severe social consequences within the smaller Islamic communities,” Jaafar said.

He said Muslims generally advocate for freedom of expression, but often have an attitude opposing the right to offend the religious sentiments of others.

“We’re not fighting against Islam,” Jaafar said of Muslimish’s mission. “We’re not fighting against ideologies; we’re just fighting for the right of people to disagree with them.”

Yasser Gowayed, Muslimish president and a mechanical engineering professor in Alabama, said he is a Muslim, although his scientific background forces him to approach religious positions with the same “merciless” criteria as he would a lab experiment.

Gowayed said his progressivism is not a product of his faith, but a journey to becoming a more open-minded person.

He said he began questioning the undisputable nature of Islam when he started doing research and eventually applied scientific principles to religion.

He urged questioning Muslims to carry out in-depth researches about the sources of Hadith, the prophet’s sacred sayings, and to dig deep into Islam’s true teachings.

|

| Ali Rizbi By Alishba Zarmeen/Purple Canvas Photography Toronto |

The Atheist Muslim

Rizvi, the self-proclaimed Atheist Muslim, is also a physician and musician. His head-scratching moniker has garnered much attention, including from a popular Huffington Post article he wrote explaining his title. Rizvi tours North America and gives talks about his upcoming book.

Rizvi, the conference’s keynote speaker, stood defiantly in front of the event’s largest audience, ready to defend his claim: you can identify as a Muslim and be godless at the same time.

At its center, Rizvi said most adherents of various religions modify their beliefs based on their birthplace and upbringing.

Even if it appears “intellectually dishonest”, he said most people will throw out harmful or impractical doctrines. Rizvi added this prevalent “cherry-picking” is the cause of the ambiguous and subjective nature of religious teachings.

Why not cherry-pick your way to non-belief?, he asked.

Rizvi also made the case that just as Jews eventually extracted their Jewish culture from Judaism, Muslims can separate their Muslim identities from Islam.

Muslims live in all corners of the world, he said; they adopt religions, but maintain the culture of their regions.

However, Rizvi’s experience has been that many aspects of Islam’s culture are universal.

These practices have enriched his life.

For example, Eid is a holiday that has taught him the importance of family. As a songwriter, Rizvi draws from musical and poetic Noha recitations, Shi’a mourning rituals accompanied by light beating on the chest. He said that just as many musicians have attributed their musical education to growing up attending church, he acquired his musical influences from his Shi’a household.

“[It] helps illustrate the important contrast between a monolithic ideology and a richly diverse people,” Rizvi writes in the Huffington Post article. “Adding another dimension to a dynamic internal dialogue that so far seems narrowly limited to the voices of fundamentalists or progressive/liberal apologists. This is our community, too. Why shouldn’t we also be allowed to speak for it?”

Leave a Reply