|

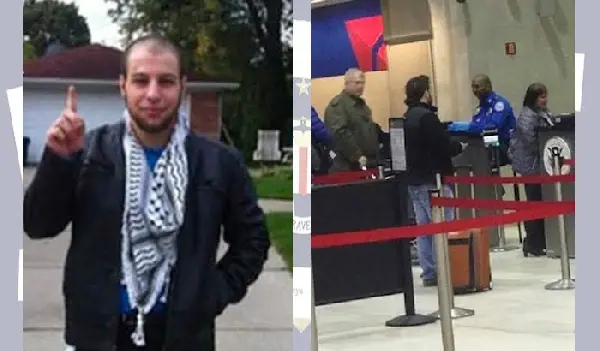

| Abu-Rayyan/ Hamdan before he was arrested at the airport |

DETROIT — Over the past two years, the FBI has arrested so many terror suspects that one would think extremists have a foothold on our shores. But a closer look at those cases reveals that the authorities were heavily involved in constructing the plots they pride themselves on foiling.

From New York, to Minnesota to Washington, we have read headlines about the arrest of young men who were detained while attempting to travel to the Middle East to join ISIS.

The national craze came to Southeast Michigan, home to the largest Arab and Muslim American communities, when Dearborn resident Mohammad Hamdan was arrested in 2014.

Hamdan, who was 22 at the time, was apprehended on the allegation that he wanted to fight for a designated terrorist organization — Hezbollah, ISIS’ foe, in Syria.

As it turned out, according Hamdan’s lawyer, the Dearborn resident was targeted by of an FBI informant who actively encouraged him to join the Lebanese militant group.

“He had applied for citizenship in the United States; he’s got tattoos; he used drugs; he’s been with women,” Art Weiss, the attorney, told The AANews after his client took a plea deal last week. “He satisfies none of the criteria that Hezbollah would utilize in allowing someone to join their ranks.”

Hamdan’s mother said he had done nothing wrong, adding that he was peaceful and physically feeble.

The young man may have been troubled, but he was harmless.

Nevertheless, the FBI appeared to pat itself on the back after Hamdan’s guilty plea, saying that the case “highlights the significance of the investigative work being done” by the bureau’s Joint Terrorism Task Force.

A more publicized case emerged in February.

Khalil Abu-Rayyan, a 21-year-old Dearborn Heights resident, had plans to “shoot up” a church in Detroit, a legal complaint by the government claimed. The story went international, making headlines in newspapers across the country as well as in British tabloids.

Abu-Rayyan’s attorney, however, argued that an FBI operative “manipulated“, “seduced” and “radicalized” his client.

The Dearborn Heights man had shown signs of adopting extremist ideology online. He did tell the FBI agent, who posed as a woman who was interested in him romantically, that he bought a gun and a mask to shoot up a Detroit church.

However, the authorities found neither the gun he described nor the mask. By the time Abu-Rayyan made that alarming statement, the government operative had explicitly expressed her support for ISIS, saying she would give up her life for the terrorists. Abu-Rayyan, in turn, told her that doesn’t want to hurt anyone, and he needs help.

Preemptive prosecution

The Intercept news website has documented several similar cases where the authorities nudge suspects to a point where they can be indicted.

Intercept editor Glenn Greenwald calls the government conduct a form preemptive prosecution, “where vulnerable individuals are targeted and manipulated, not for any criminal acts they have committed, but rather for the bad political views they have expressed.”

While the FBI says it approaches and reviews each case individually based on information that may not be available to the public, civil rights advocates argue that the government is incriminating speech and targeting individuals and communities based on their beliefs.

Muslim groups worry that the highly publicized terrorism trials are contributing to the rising tides of Islamophobia and giving hate groups proverbial ammo to smear Islam.

Moreover, they also say such methods are ineffective.

“Problematic”

While some terror-related cases may fit the literal definition of entrapment, the term is subjective in a legal sense, according to attorney Steve Fishman.

The government needs to have a reason to send an informant or undercover agent to incriminate someone. That is called a “predisposition.”

When the authorities have genuine fears about a person’s behavior, they can employ such tactics.

The predisposition, in itself, could be legal. Voicing support for ISIS or Hezbollah on social media is protected by the First Amendment, but it gives the FBI a legal pretext to use undercover operatives to “get” the suspect.

Fishman does not see a problem with lawfully employing undercover agents to indict potential criminals. He gave an example of decoy children on Internet forums, who are used by the government to identify and arrest pedophiles.

However, he has reservations about the use of civilian informants who may have an existing personal relationship with the suspect.

In that sense, Abu-Rayyan was predisposed to violent extremism because he watched and shared ISIS execution videos, but during pre-trial hearings, his lawyers stressed that the FBI operative kept pushing him towards radicalization.

“Don’t do anything That will hurt u Yourself or other people (sic),” the defendant wrote to the agent, according to court documents.

In another exchange, she tells him she is willing to give up her life to ISIS.

“Your (you’re) young and confused,” Abu-Rayyan responded.

Fishman said the government should not actively encourage suspects to commit crimes.

“I have a big problem with that,” he said.

Weiss, Hamdan’s lawyer, said it is challenging to get an impartial jury in cases involving allegations of terrorism because of the prevailing anti-Muslim political rhetoric.

Fishman said those concerns are not unfounded, especially given the popularity of politicians like Donald Trump.

“You’d be a fool to ignore that there is a considerable prejudice against Muslims and against people of Arab descent,” he said.

Fishman added that fear of bias can play into a defendant’s choice to take a plea deal. He said attorneys are conscious of this anti-Muslim climate.

The new ‘war on drugs’

Attorney Bill Swor complained of grey areas of the law when it comes to entrapment. He said legal interpretations are affected by the post-9/11 political atmosphere.

According to Swor, claiming entrapment is challenging because defendants who want to make such a legal argument have to admit that they were going to commit the crime, and argue that it was entirely the government that led them to that point.

“The government takes noise or talk and puts it into action,” Swor said.

Most Lebanese American Dearborn residents hail from southern Lebanese villages, where Hezbollah enjoys overwhelming popular support.

Swor said the government would not point to a suspect’s sect or national origin in a court of law to portray him as a Hezbollah supporter.

But.

“Implicitly, in the way that the government approaches these cases, one could assume that they view the community as having a predisposition,” Swor added.

Asked how far government agents can legally go in pushing suspects to commit crimes, Swor said he hopes to find the answer to this question in his lifetime.

He referred to the FBI’s behavior in a recent case where an undercover agent was explicitly pulling the suspect towards violent extremism as “absolutely outrageous.”

“Twenty years ago, I think that would have been viewed as too far,” Swor said. “But today, in this atmosphere, it hasn’t been said that that’s too far.”

The attorney, who has represented several defendants in similar cases, warned against believing that suspects have an intention to act upon the actions they said they were going to take.

“You can go into any coffee shop, any restaurant and you hear outrageous things,” he said, adding that violent individuals often do not reveal their plans or discuss their intentions.

The attorney said the Constitution allows people to make extreme statements.

“Therefore, I don’t think it’s fair either to the community or the individual defendant to attribute an intention to act, just for hateful speech,” he said.

Despite the questionable legality of the government conduct when it pushes suspects towards criminality, Swor thinks it is unfair.

“For the government to take people who are sitting around and just talking and to encourage them and provide them with the means to do something wrong, it is just contrary to our legal traditions; and I think it is immoral,” he said.

Swor said such tactics do not make America safer.

There is a political component to law enforcement that creates an incentive to entrapment-like policies, he added.

“They do it because it gives people a false sense of security,” Swor said.

He wondered why is it in anyone’s interest to help vocal suspects turn talk into action.

“Which is cheaper, which is faster, which gets more publicity?” He asked. “Sitting and watching and spending thousands of man hours, looking into real problems or getting someone to do something?”

Swor compared the authorities’ anti-terrorism approach to the war on drugs, which he said led the government to cut corners about civil rights in law enforcement.

“The war on drugs did not reduce drug use, but people went to prison ungodly amounts of times,” he said. “What we’re seeing today with these terrorism cases is the same thing.”

|

| Jess Sundin |

Two years of spying

Earlier this year in Minnesota, three Somali American men in their early 20s were convicted of trying to join ISIS. The attorney of one of the defendants unsuccessfully argued that the government entrapped his client.

The lawyer said the informant, a friend of the suspects who was paid more than $100,000 by the FBI, pushed them to pursue the terrorist group, a local publication reported.

Jess Sundin, of the Committee to Stop FBI Repression, is all too familiar with the Bureau’s questionable methods.

Not far from where the young Somali American men were tried, an FBI agent posed for two years as a member of a leftist group, resulting in raids of the homes of several members of the organization.

Sundin was a member of the Antiwar Committee between 2008 and 2010. The FBI sent an undercover operative to infiltrate the ranks of the organization after the group’s protests at the Republican National Convention in 2008.

Sounding genuine, the undercover agent would repeatedly urge the leftist group to support blacklisted Palestinian and Colombian organizations in the name of solidarity, Sundin said.

“She would ask once and again and again what would seem like an innocent question; and it would feel like it was coming from a sympathetic place,” she said, describing the agent’s behavior.

According to Sundin, the FBI operative took special interest in coalition work, particularly with local Somali American groups.

“From her position with the Antiwar Committee, she spied on Muslims and other organizations in the community as well,” Sundin said.

In 2010, after more than two years of spying and incitement by the agent, the FBI raided and searched homes of members of the movement and subpoenaed others.

The government called on leaders of the Antiwar Committee to testify in front of a grand jury; they refused.

“They wanted any correspondence with anyone living in Colombia or Palestine,” she said.

Sundin suspects that if the Committee had fallen for the agent’s suggestions, she and her colleagues would have been brought up on terrorism charges.

“Specifically, the search warrant was searching for evidence for material support to terrorism,” she said.

Sundin finds parallels between the Antiwar Committee ordeal and recent terrorism cases. She said the authorities are trying to criminalize people for their thoughts.

“There isn’t anything normal about the idea that an officer of the government would spend years lying to citizens of this country and try to convince them of— or suggest until they take it up as their own or make seem attractive— ideas that are illegal,” she said.

“Not entrapment”

David Gelios, FBI special agent in charge for the Detroit division, told The AANews earlier this month that the bureau deals with each case individually. He added that the agency has rules to avoid entrapment.

“Frankly, if there were issues of entrapment in any thing we do, that makes it very, very difficult for the U.S. Attorney’s office to prosecute these cases,” he said. “So a great amount of effort is given to preventing any situations of entrapment.”

The local FBI chief added that a judge can decide if entrapment occurred.

“Entrapment is not defined by the public perception, based on what little they know about an investigation,” Gelios said. “It’s not based on their conclusion that there was entrapment involved, because they don’t have all the facts to make that sort of determination.”

As for the use of informants, he said members of the community who come forward with information do not necessarily have a formal relationship with the FBI.

“Some do it for a variety of motivations more formally, and those who do you could call an informant,” Gelios said. “Some are just citizens who call us with information. All of it is about providing us information about people who are potentially breaking federal laws or potentially are a threat to our national security. So I make no apologies for the fact that we depend on the public for information.”

At a meeting at The AANews’ offices in August, Gelios said the FBI conducts case-based, subject-specific investigations and does not target groups because of their religious affiliation or national origin.

(Hassan Khalifeh contributed to this report).

Leave a Reply