DEARBORN — For the last few months, all eyes have been on the city’s government and how it will respond to calls for proper representation of Arab Americans, who make up about half of its population. Many also have deep roots in the community.

As the city’s residents and officials argue over the fate of the statue of famous segregationist and former Mayor Orville Hubbard – following its removal from City Hall in 2015 and relocated to the lawn of the Dearborn Historical Museum – some community members have wondered whether the city is ready to erase exalted symbols of racism.

At the Arab American National Museum, Yasmine Badaoui recited her poem at an open mic event on Sept. 6 titled “Racism Smiles On S. Brady,” referring to the statue and the street where the Dearborn Historical Museum is located.

“The smoke stacks in the Southend, my grandfather’s grape leaves conquering a fence in the east, the mighty oaks in the west drop leaves at my feet, a bronze statue whispers the words of my grandmother: ‘Sand n****r,'” Badaoui began her poem that painted a picture of a Dearborn with an identity crisis.

Inside the main museum structure, originally a 13-building arsenal during the Civil War, photos, artifacts and living quarters tell the story of Dearborn from the mid-1800s until today. Take a tour and a noticeable lack of Arab American history comes into view.

Museum administrators told The AANews they face numerous challenges in showcasing the Arab American story, but look deep enough and you’ll find that story rooted in every corner of Dearborn’s history.

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of WWI, the museum’s main display features relics of the city’s involvement in the war and the birth of Dearborn as it’s known today. A century ago, Ford Motor Company opened its Rouge River and other plants, said Andrew Kercher, assistant chief curator at the museum.

In 10 years, this small Detroit suburb went from having a population of a few thousand Whites to a bustling city of more than 60,000 resident from all over the world. A great deal of them were Lebanese immigrants, but archival records identifies them as Syrians who lived in the Southend.

A staircase leading to the archives upstairs houses old maps, school yearbooks and detailed versions of the Polk Directory, where people often research their houses and genealogy.

But perhaps the most explicitly Arab American artifact is a medium-sized folder titled “Arabs.” It includes a collection of photos dating back to 1930, showing portraits and events like protests against the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in front of City Hall and the old offices of ACCESS in the Southend.

A few weeks ago, the museum bolstered its outreach efforts in the Arab American community by printing about 1,000 Arabic brochures about the museum, made possible by a grant through the Dearborn Community Foundation.

But even then, Kercher said the Dearborn Historical Museum faces a challenge of being positioned near the Henry Ford Museum and the Arab American National Museum. Most visitors to the city are drawn to The Henry Ford and Arab Americans are drawn to the AANM, he said.

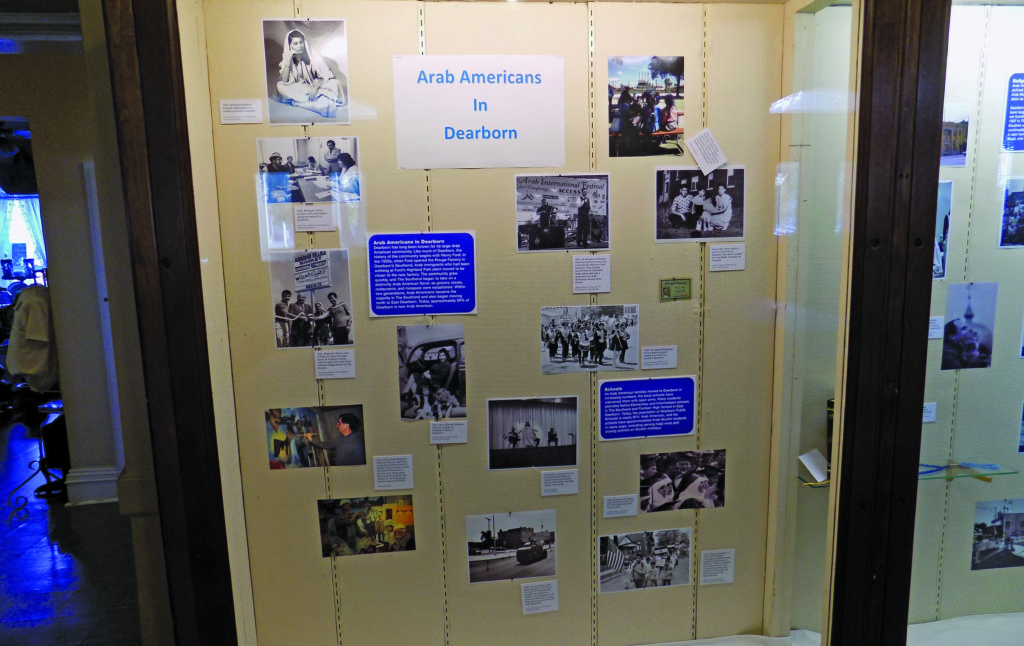

A 2016 exhibit featuring archival photos about the Arab American community in Dearborn

He added that while the Historical Museum has set up showcases in the past on Arab American history, using the collections from the Arab American National Museum, it’s had a hard time finding artifacts – not only photos – that could be donated that are unique to the story of Arabs in Dearborn.

“It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Kercher said. “Not many Arab Americans visit because there are not many Arab Americans items, and it’s hard to tell that story without the items and the volunteers from that [ethnic] group. It’s a cycle that we’re trying to break.”

He pointed to little to none Arab American museum volunteers and only one Arab American historical commissioner, Mohamed Sion.

Pointing to crumbling trimming around a museum building, Kercher added that under-funding hinders the museum from marketing and adding exhibit space. Instead museum officials have turned to holding social events, like a beer tasting party.

“We are the smallest city department by far,” he said.

Once the budget grows and space becomes available, Kercher said the museum plans to install permanent exhibits relating to what visitors mostly ask about: The museum’s history as a war arsenal, Ford Motor Co. and Arab Americans in Dearborn.

At the main building’s side street entrance, the bronze statue of a waving Hubbard greets visitors at the parking lot. It was moved from the front of the building following some contentions regarding its location, but many still see its presentation as a celebratory tribute to the long-time mayor, instead of a historic artifact.

A poll published on social media by The AANews that received a modest-sized response showed that about half of those polled want the statue completely removed and the half want it moved inside the museum.

Kercher said he believes the statue is at the appropriate place – at a museum, instead of at City Hall.

“It’s a great shame we don’t have any kind of label on it,” he said, adding that he had already drafted a write-up that’s set to be reviewed by city’s historical commission.

Jack Tate, chairman of the historical commission, told The AANews the museum has seen a “fantastic growth” in visitors over the last five years, and that it aims to be more connected with the Arab American community, including initiatives like regularly sharing archival data with the Arab American National Museum.

“Dearborn’s got a very diverse community,” Good said. “We do have to showcase that more, and that’s what we plan to do in the future.”

Leave a Reply