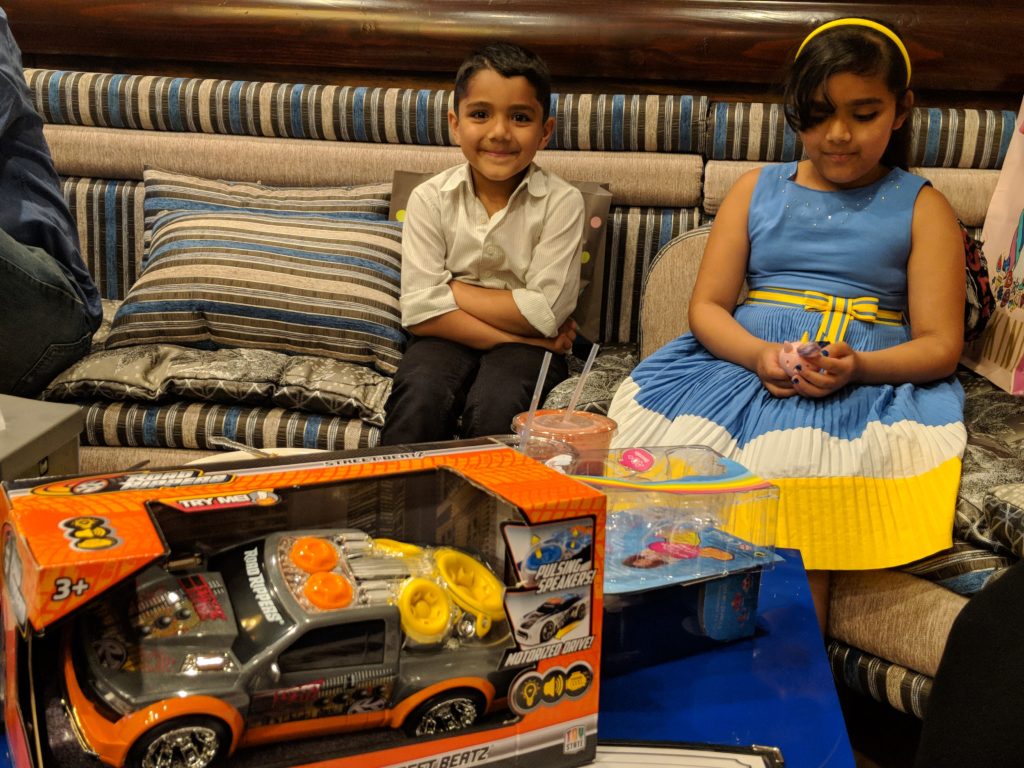

DEARBORN — Farah, a 9-year-old girl flaunting a colorful dress, proudly hands a drawing she made to a woman who’d just gifted her a toy doll.

Farah, whose name translates to “joy” in Arabic, said she loves drawing and would someday day like to teach art. Mohammed, her 6-year-old brother, sports a black bandana. He’s pretending to be a pirate and examines his new toy truck.

They seem as content and hopeful as most children, but their fate didn’t turn out like the kids they used to play with.

At an iftar dinner at a local restaurant, their parents, Akram and Diana Alchalabi, shared with The AANews their journey from a war-stricken Syria to quickly turning around dire circumstances as refugees in Michigan.

“We did it for the kids,” said Akram Alchalabi, a humble, 40-year-old man who designs and installs luxury curtains for a living.

Farah and Mohammed Alchalabi with their new toys

It’s been about a year and half since the Syrian refugee family moved to Michigan and it’s during Ramadan that Alchalabi said they’ve been able to measure how well their assimilating to their new lives.

This year’s spirit is a long way from last year’s, when Ramadan meant extra prayers and Quran reading with the kids, followed by a modest meal before bedtime.

They were lonely and strangers to everything from roads, neighbors and a system that required loads of paperwork and follow-up, Alchalabi said.

In their first few days in the state, the family rented a home in Dearborn Heights and Alchalabi quickly found a job as an electrician, but the rent cost far from what they could afford.

That’s when he met Maria Kabbani, a Dearborn resident who handed toys to the children.

Kabbani said she founded Orphans of War, a non-profit that provides basic needs to refugee children and their families in overseas camps and in Metro Detroit, in 2016 after noticing a large influx of Syrian refugees. Kabbani was at the same time researching why unaccompanied minors were never allowed to come from Syria, and found out that most of the orphans were detained in refugee camps.

She added that most families she assists have become largely sustainable, but that there was a time she visited households who “had absolutely nothing, no food to eat, no electricity.”

Kabbani said she helped find the family a more affordable home in Dearborn and hosted an iftar dinner for refugees at a local burger joint last year.

That dinner was the first time they had attempted to make friends – and an experience that changed their lives, Alchalabi said.

Ramadan in Syria is a completely different experience, according to Alchalabi. They miss the large family gatherings and bustle of people rushing to buy food from street vendors before mosques blared the call to prayer, giving permission for locals to break their fast, he said.

“When you walk the streets a 4 a.m., it’s like walking at 4 p.m.,” he said.

Alchalabi especially misses enjoying naa’em, a traditional Syrian sweet served only during Ramadan, which he has not been able to find at stores in Michigan.

But the Alchalabi family has traveled a long way since then and has come to embrace breaking their fast with neighbors of diverse nationalities. They also now know where most nearby grocery stores are located.

Farah and Mohammed, who now speak near fluent English, experienced Ramadan in Jordan, where the family initially sought refuge for four years before applying for refugee status with the United Nations and were referred to the U.S.

The children miss their grandmother’s home cooked meals and playing with their cousins in Jordan. However, their parents have found creative ways to keep the Ramadan spirit alive and make them feel more at home.

The Alchalabi family’s Ramadan tree

This Ramadan, Alchalabi said their home is decorated with lights, banners and even a Christmas tree. It’s uncommon for Muslims in Syria to put up a Christmas trees, but it serves its purpose of maintaining a festive atmosphere.

“I don’t consider the Christmas tree as a religious symbol, but a symbol of happiness for everybody,” he said.

Since last year’s somber Ramadan, Alchalabi said his family has developed relationships with refugee families like theirs, enjoyed Thanksgiving dinners and even forged close ties with Jewish neighbors.

“The beauty of Ramadan is the communal aspect,” he said. “This iftar is not about the food, but for me to be with you and share stories. Your social circle starts to grow as time goes by.”

He added he’s thankful to be working in the same trade as in Syria, where he also made a living in the curtain-making industry.

Kabbani said she’s helped dozens of struggling refugee families in Southeast Michigan, but few stand out much as the Alchalabi family.

As soon as Akram Alchalabi earned his first paycheck, he donated $100 to Syrian Orphans in order to aid another refugee family, Kabbani said. He continued to do so every month until his boss found out and began allocating extra money for him to donate.

“It took him only a month to turn his situation around,” Kabbani said. “And it took him only a month to start paying it forward.”

Proud to have been approved by the Red Cross to donate blood, Alchalabi said that last month was his first time doing so.

He said this year’s Ramadan in Dearborn feels closer to home, but is keen on taking advantage of the vast opportunities America has to offer and is determined to give his children a strong education.

“It felt reborn when I arrived in Michigan,” he said. “But whether in Syria or in America, you forget where you are, because happiness comes from inside.”

While playing with her doll, Farah looked up from her plate and smiled.

The AANews reporter Sarah Kominek contributed to this report.

Leave a Reply