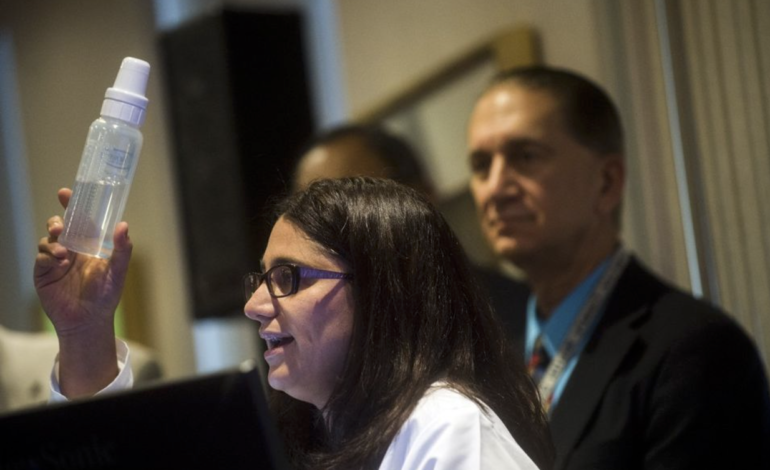

FLINT — Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, known as the primary whistleblower in the Flint water crisis, documented her personal experience of seeking proof of lead poisoning in Flint’s children in her book “What the Eyes Don’t See.”

The book not only describes her struggle bringing the Flint Water Crisis to the public, but includes formative stories from her life and upbringing that contribute to her approach in dealing with the crisis.

“It’s a book about activism, a book about resistance and so much a book about hope,” she said. “I think it’s important for Arab Americans to read this book and to recognize that it’s also very much an immigrant story.”

She said if it weren’t for the current administration’s treatment of immigrants, she might not have included so much of her own story.

“I knew I wanted to include a lot of me in there because you can’t understand who I am and what I did, my role in this crisis, without understanding my roots and where I came from,” she said, “that history of social justice from an immigrant lens.”

In “What the Eyes Don’t See”, Hanna-Attisha tells the story of her family’s emigration from Iraq to Britain, where her father received a scholarship to finish his Ph.D. in metallurgical engineering at the University of Sheffield in the late 1970’s as Saddam Hussein rose to power.

“Lady Liberty opened her arms and welcomed me into this country,” she said. “We were a family fleeing an oppressive, tyrannical, fascist regime and we were coming her for opportunity, freedom and democracy.”

Hanna-Attisha and her family immigrated to the United States in 1980 to Houghton, Michigan when she was 4-years-old; there, her father continued his education as he pursued a post-doctorate degree.

She said she vividly recalls childhood inspirations which drove her to study medicine, including the television program “M*A*S*H”, with characters like the passionate Dr. “Hawkeye” Pierce and Lebanese American Maxwell Klinger from Toledo, Ohio.

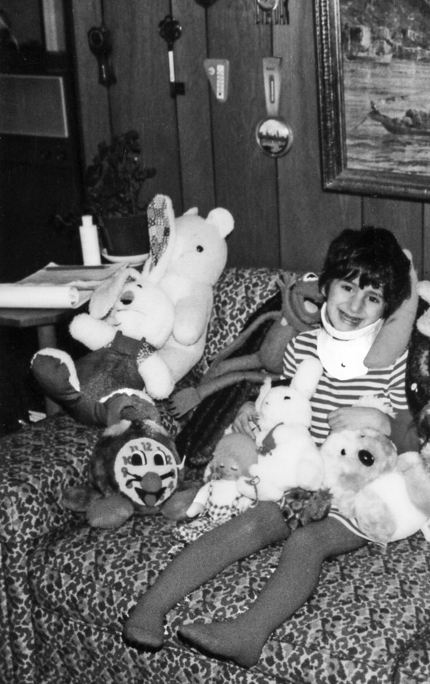

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha in a neck brace at age 5

Hanna-Attisha was seriously injured with a broken neck and fractured jaw in a car accident with her family not long after arriving in the United States, a time when they knew little English. In her book, she recalls one of her female doctors with dark skin and hair comforting her.

She said she saw a juxtaposition when, 30 years later, she was able to be the doctor comforting a little girl with dark skin.

“It became very much my obligation to make sure she was going to be okay,” she said.

She said her family, specifically her grandfather, whom they call “Haji”, shaped her beliefs and perspectives that directed her to humanitarian work and gave Hanna-Attisha her name: Mona.

“He was this absolute humanist, he loved all people,” she said. “Back home in Iraq his best friends were of every religion and sect and every different kind of class. He believed in people, the capacity and power of people.”

She said when her family relocated to Royal Oak while her father worked for General Motors, her mother helped immigrant students from the Middle East assimilate in Detroit by teaching English-as-second-language courses.

“It’s evidently in my DNA,” she said.

She said her family never kept from her the knowledge of dangers back in Iraq. In her book, she recalled her father showing her pictures victims of Saddam Hussein’s attack on Halabja in 1988, when 5,000 people, mostly women and children, were killed with chemical weapons. She said throughout her life, the image of a dead baby never left her brain.

“Like most immigrants who come here because of injustices back home, I realized how lucky I was, but I also realized what evil regimes can do to vulnerable populations and what power in the wrong hands can do to marginalized people,” she said.

Hanna-Attisha said it was her family’s exposure to experiences of injustice that gave her the drive to do work for underprivileged people.

“I think because of that realization I’ve always been maybe more awake and alert, more tuned into the injustices around me,” she said. “Because of that background and up-bringing, I’ve committed myself and my career to serving the most vulnerable populations; to giving back, but to making sure that I could use my incredible privilege and opportunity to make sure that others have that same access to the American dream that I did.”

Hanna-Attisha first began her education in environmental health at the University of Michigan before attending medical school at Michigan State University, finishing her pediatric residency at Children’s Hospital of Michigan.

She said she chose pediatrics because she believes in preventive care and advocacy.

“So much of what we do in medicine, especially for older adults is too late,” Hanna-Attisha said. “Pediatrics is at this really critical intersection of not only clinical care but also prevention.”

That’s why she said she decided to go back to get her master’s degree in public health and health policy from the University of Michigan.

“What I love about pediatrics, in that integration with public health, is the ability to advocate for kids,” she said. “We as pediatricians are the voice of children.”

“The kids ground me and inspire me,” she added. “The kids are the ones that make me wake up every day. When you love what you do, and I love what I do, it is not work.”

Throughout the book, Hanna-Attisha refers to the children of Flint as “my kids.” She said her two biological daughters, Nina and Layla, who are 9 and 12-years-old respectively, say it’s as if they have 6,000 siblings.

“It’s a privilege and a blessing to be able to care for these kids,” she said. “These children are no different than my children.”

Hanna-Attisha said she hopes her book inspires people to work in their own communities to make a difference.

“Without passion, you don’t have drive and you’re not fully committed,” she said. “Writing this book, I relived all of those emotions. I wanted the readers to feel what I was feeling and to dare them to realize this was happening on American soil; and to dare them to commit to opening their eyes no matter where they are and to take action to improve the lives of our most vulnerable children.”

Leave a Reply