DEARBORN — One day in the summer of 1915, Henry Ford and his top lieutenants gathered at a spot near Miller Road and the Rouge River to survey the flat farmland and talk about the future.

Ford, whose huge Highland Park plant was producing his world-changing Model T automobile on a revolutionary assembly line by workers earning the remarkable wage of $5 a day, had a hunch that someday he would need a new manufacturing center, with water access. So he decided to dispatch a team of real-estate agents to buy up land along the Rouge, which was then little more than a shallow stream.

Ford was born in 1863 on a farm near Greenfield and Ford Roads, but he had spent most of the previous three decades in nearby Detroit and the dense enclave of Highland Park, as Detroit was exploding into the fourth most populous city in the nation.

“I don’t like to be in the city,” Ford told a colleague. “It pins me in.”

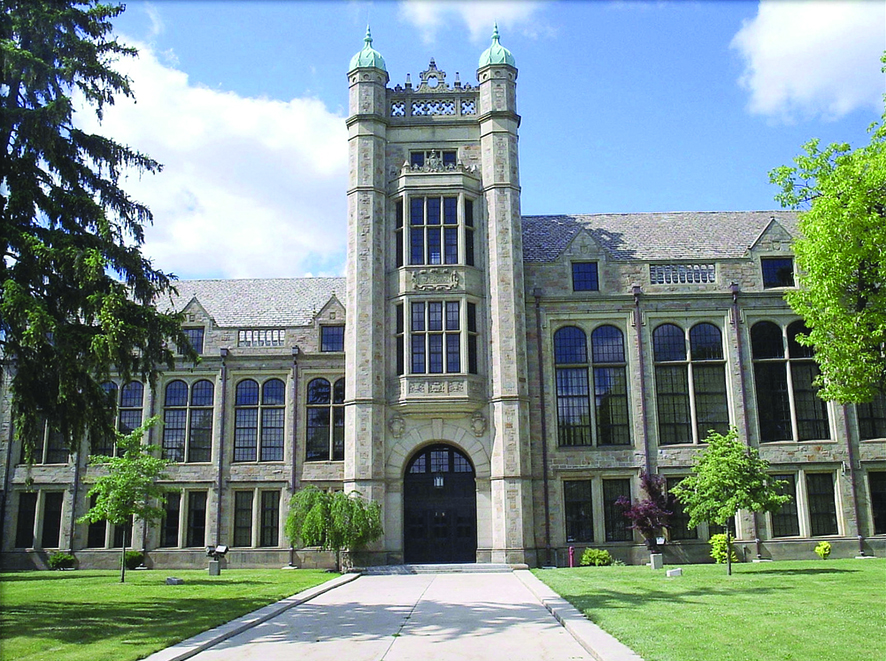

Fordson High School was built in 1928, one year before the creation of Dearborn

Construction of Ford Motor Company’s Rouge plant began in 1917. By 1927 the Rouge was probably the most important industrial complex in the world — a collections of large factories and 75,000 workers — 5,000 of whom did nothing but clean up — at which raw materials famously went in one end and automobiles came out the other. Vanity Fair magazine published arty photos of the Rouge and called it “the most significant public monument in America.”

Dearborn might have taken great pride in the plant. But the plant at that time was not located in Dearborn.

The John Schaefer Building, on the corner of Michigan Ave. and Schaefer was built 1930 and today is the headquarters of the Masri Medical Center

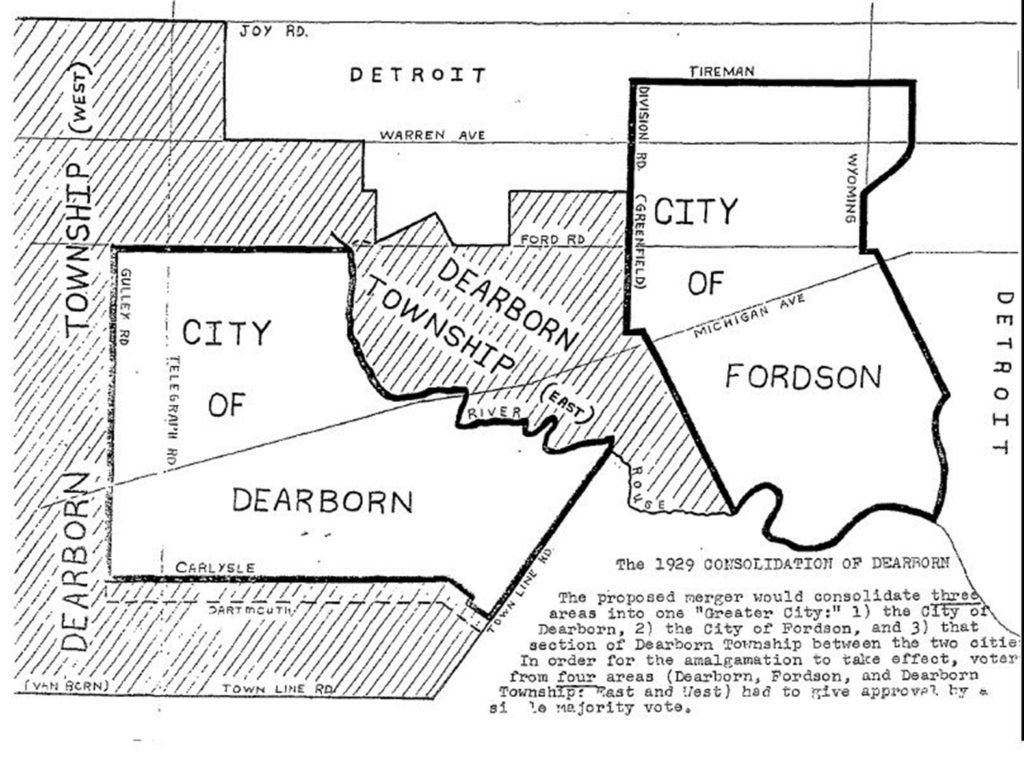

Ninety years ago, the Rouge plant was located in the city of Fordson, which just a few years earlier had been known as Springwells Township. The old town of Dearborn sat about three miles west of Fordson, whose western limits were Greenfield Road. The land between Fordson and Dearborn was known as Dearborn Township.

But that arrangement would not last long once the Rouge was running at full tilt. Starting in the late 1920’s, Henry Ford spearheaded a campaign to merge the three communities into the modern city of Dearborn. It’s not one of Ford’s better-known accomplishments and Ford tried to downplay his involvement, possibly because the politics of a merger were complicated and bound to be messy; and the leadership of Ford — by then one of the wealthiest and best-known people in the world — would have both advantages and disadvantages.

The old Dearborn City Hall, on Michigan Ave. and Schaefer, was built in 1922 and now is Artspace City Hall Lofts

Joining the 20th century

The Rouge plant jolted once-sleepy Fordson and Dearborn into the 20th century. Seemingly overnight, towns once characterized by farms and small businesses were bursting with well-paying industrial jobs, thousands of homes, more sophisticated commercial establishments and such urban infrastructure as sewers, paved roads and transit. By the mid-1920s, Fordson had become an industrial center and had grown to 26,000 residents, and housing was in short supply.

Dearborn was more residential than Fordson and less financially secure in 1927. Henry Ford had built the Ford homes south of Military and Michigan for the workers at his nearby tractor plant and the area around Michigan and Monroe was an active business district. But development in Dearborn lagged behind that of Fordson and its tax base was puny. Dearborn’s population was 9,000.

Dearborn Township, in which Ford’s Fair Lane residence was located, had only 500 residents, mostly on farms.

The idea of the merger gained steam in 1927. Rumors began circulating, and the idea acquired a name — “consolidation.”

Consolidation

A committee of leading citizens was formed. Clarence L. Parker, the committee chairman, told the Detroit Free Press that politics had nothing to do with the idea, but that officials envisioned the efficiencies to be gained in joining together and how the combined tax base could finance improvements in all three areas.

Parker and other leaders claimed Henry Ford was not involved in the movement to consolidate the three communities. But that was untrue. It was Ford’s idea. He was the biggest taxpayer in both Fordson and Dearborn and it was Ford who got the ball rolling. One of Ford’s top aides, Ernest Liebold, had summoned officials to the first meeting. Ford himself showed up at the meeting and continued the ruse that he wasn’t involved, reportedly saying, “Whoever suggested this idea…that’s a bright, brilliant one.”

The Dearborn Historical Museum is the oldest building in the city of Dearborn, built in 1837

Years later, the mayor of Fordson, Joseph Karmann, said Ford had initially approached him with the idea of the merger. If the merger succeeded, Ford offered to build a new police headquarters, fire department, hospital and office space, according to a 1979 article in the “Dearborn Historian” by Ralph G. Fader.

Karmann told another reporter that Ford had said, “Joe, why don’t you people annex the city of Dearborn and part of the township in between, where my estate is? Then I wouldn’t have to deal with three governments.”

Michigan Ave. in Springwells Township, now east Dearborn, in 1910

Merger plan faces opposition

It would have been difficult to turn down Henry Ford in 1927, especially for small town officials, even if Ford was a neighbor. As David Lewis wrote in his 1976 book, “The Public Image of Henry Ford”, Ford Motor Company by the late 1920s was receiving “more publicity and had greater prestige than any other business institution in America.”

Much of the reason for that was Ford himself, who had become a global folk hero because of his industrial innovations and quirky personality.

And the local officials did not turn down Henry Ford; they snapped to attention, jumping on the consolidation plan.

It wasn’t easy.

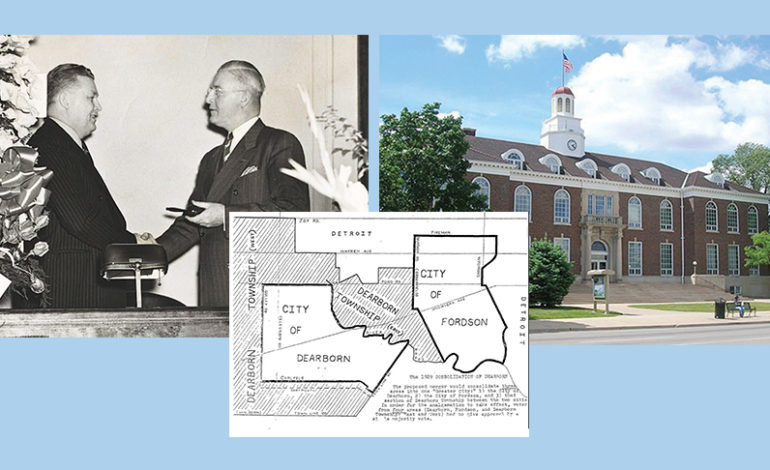

Henry Ford with his cousin Clyde Ford, Dearborn’s first mayor

A number of business leaders from Fordson opposed the plan, knowing their city services far surpassed those of Dearborn. Fordson’s taxes were also lower than Dearborn’s, thanks to Ford Motor, which paid 75 percent of the city’s tax burden. And assessments were much higher in Fordson.

Opponents in the Save Dearborn Association worried that Dearborn’s identity — forged over the previous century of settlement — would be lost in a merger.

In 1928, at a public meeting before the vote, tempers flared. Some speakers accused Ford Motor officials, who lived in Dearborn, of supporting consolidation as a way to tap into Fordson’s tax base in order to improve Dearborn.

“There has been a lot of heckling here tonight,” noted Fordson Mayor Floyd Yinger, who stood up for his town. “I am for Fordson. I believe in the city of Fordson.”

“Dearborn has nothing to compare with what we have in the city of Fordson,” said Karmann, Fordson’s former mayor. A merger, he said, “would be suicide.”

“The people of Dearborn always thought that they were too big for us, a little better than we were,” said William Kenner, a Fordson backer. “Fordson is a city of working men. The working man can think for himself.”

Henry Ford released a letter late in the campaign that received wide publicity.

“One central government would be better to direct the future development of this area,” he wrote. “Public funds should be spent in a manner that will serve public needs for a greater and longer purpose, which can only be done through a centralized administration.”

Former Dearborn Mayor Orville L. Hubbard (1903-1982), known as the most outspoken segregationist north of the Mason-Dixon line, stands defiantly in the center of Michigan Ave. outside Dearborn City Hall

New city emerges

Voting took place on a sunny late spring day, but turnout was light. Consolidation passed easily in Dearborn and Dearborn Township, but just squeaked by in Fordson, where, out of 2,861 votes cast, the consolidation forces prevailed by just 85 votes.

With the three communities destined to be united in early 1929, the next order of business was to come up with a name for the new city. Some suggestions were Dearson, Fordborn and LincolnFord.

In the end, voters overwhelmingly ratified a decision by charter commissioners to go with Dearborn, largely for historical reasons. There was little emotional attachment to Fordson, whose 1925 name change from Springwells was done to honor Henry Ford and son Edsel for what they had done for the community.

Heather B. Barrow, in her book about Ford’s impact on the growth of suburbia in the United States, “Henry Ford’s Plan for the American Suburb”, writes that Ford wanted to transform Dearborn into a model community for working people who could enjoy the best of both city and suburban lifestyles.

Wagner Place on Michigan Ave., now part of the Ford Motor complex, in a photo dated 1896

“Henry Ford’s ultimate goal was to turn it into a suburb for the masses, one fitting for American wage earners and capable of turning workers from any background into good citizens,” she writes.

Consolidation was hardly the last thing Henry Ford did for his hometown.

Several months after Dearborn, Fordson and Dearborn Township united, Ford, joined by Thomas Edison and President Herbert Hoover, dedicated Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum — now known collectively as The Henry Ford — the largest indoor-outdoor museum complex in the United States.

There was no doubt about its location: Dearborn, Michigan, U.S.A.

-Bill McGraw, a 37-year veteran journalist and member of the Journalism Hall of Fame, wrote this article special to The Arab American News.

Leave a Reply