DEARBORN – Few personalities have had a bigger impact on the civic standing and political relations of Arab Americans in Metro Detroit than longtime attorney and Dearbornite Abed Hammoud.

Hammoud’s dynamic career, with decades of professional legal experience at both the state and federal levels, reflects the social and political mobility many Arab Americans have enjoyed in the past 20 years.

Beyond having an impressive career, however, Hammoud has been one of the central figures in coalescing political power within the wider Arab American community in Michigan and promoting public service among younger Arab American professionals.

As evidenced by an energized and inspired Arab American community that is now intensely engaged in current political discourse, Hammoud’s efforts in mobilizing a previously disparate community towards shared goals have rippled out into the present political landscape in the state.

A budding legal career creates opportunities

Hammoud left his native Lebanon for France in 1985. He then immigrated to join his family in the U.S. in 1990 after receiving bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering in Lyon, France.

“The first thing I had to do was to learn English,” Hammoud told The Arab American News last week. “I did this at Wayne State University, where I also received a master’s in business administration (MBA).”

“While going to school and attending community events, I realized my love for politics,” he said. “I also realized that a lot of people who do politics also practice law. Lawyers play a great role in American life.”

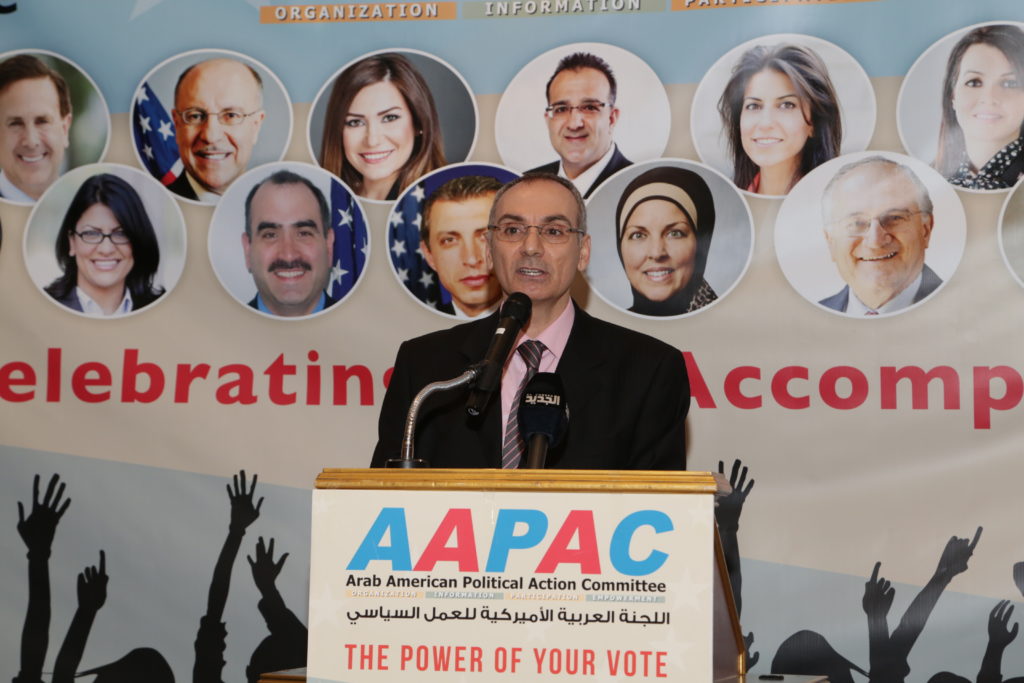

Abed hammoud speaking at one of AAPAC’s annual banquet dinners

His interest in politics and insistence from his father to pursue further education beyond his master’s degrees led Hammoud to attend law school at the same university.

He saw in law school an opportunity to learn about his adopted home and further integrate into American society.

“I had only been in the country for two years before attending law school,” he said. “I wanted to learn more about the American system and I knew law school would teach me a tremendous amount about this country’s culture, history and traditions, which it did.”

During law school, Hammoud interned at the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office.

Watching a cross examination during a high-profile murder case, Hammoud was struck by the realization that he had found his calling in prosecutorial law. After graduating from law school, he was hired as an assistant prosecuting attorney, a highly sought after and competitive position which Hammoud went on to hold for nearly 15 years.

During his years as a prosecutor, Hammoud continuously encouraged young Arab and Muslim Americans to think about public service and to seek positions in local, state and federal government instead of only aspiring to work in the private sector where they could earn more money.

In fact, at the behest of Hammoud and with his recommendation, several Arab American law students interned for Wayne County and a few of them were later hired as assistant prosecutors and were subsequently appointed to a judicial position or higher with the Attorney General and in other public offices.

Former Assistant U.S. Attorney Abed Hammoud: “I wanted to dispel the myth that Arabs and Muslims cannot hold positions as prosecutors in the federal government”

At the end of 2006, Hammoud was assigned by Prosecutor Kym Worthy to lead Wayne County’s Deed and Mortgage Fraud Unit, a task force formed by the prosecutor, sheriff and the Wayne County Register of Deeds, for which he later obtained federal grants in order to expand his team. The task force became nationally recognized and won several awards and is still in existence today.

Hammoud also suggested and drafted new laws to tackle mortgage fraud and other financial crimes. His suggestions were later adopted by the Michigan legislature in six bills signed into law in 2011. Due to an overlap in federal bank fraud and mortgage fraud cases, Hammoud’s expertise on the issue got attention from federal agencies and prosecutors.

An opening in former U.S. Attorney Barbara McQuade’s office became an opportunity to shift his prosecutorial career to the federal realm.

“It was a natural transition,” Hammoud recalled. “Working in white collar crime in Wayne County certainly helped. I always wanted to work in the federal government and contribute a diverse background, including languages that (the field) can benefit from.”

In May 2011, Hammoud was sworn in as an assistant U.S. Attorney in Detroit and was assigned to the White Collar Crime Unit.

“I wanted to dispel the myth that Arabs and Muslims cannot hold positions as prosecutors in the federal government,” he said. “I also wanted to show that even naturalized citizens can be trusted to serve their country with the utmost integrity and competence.”

Hammoud recently resigned from his post as assistant U.S. Attorney to begin a new chapter in private practice

Hammoud’s linguistic expertise and cultural knowledge of the Middle East led him to be chosen to serve as legal advisor for the Department of Justice and State Department at the U.S. Embassies in Egypt and Kuwait during the years 2016-2017.

In his eight years as assistant U.S. Attorney, Hammoud handled more than a few high-profile cases. He has recently resigned from his post to begin a new chapter in the private sector by starting his own law firm.

“It’s something I’ve been thinking about for some time,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to build a private practice that is competent and ethical. I believe providing good legal representation is also a service to people, especially those in ethnic communities. These communities aren’t always well served by attorneys who may not understand their culture, their issues and even their language.”

He did clarify, however, that his firm’s goal is not limited to serving Arabs and Muslims, but rather to serve all who are in need of good legal representation, especially in the federal or state criminal law arenas.

Mobilizing Arab American political power

After seeing a need for real campaigning and endorsement mechanisms for Arab Americans interested in political careers, Hammoud founded the Arab American Political Action Committee (AAPAC) in 1998. He first established and registered the organization and then convened a group of Arab American professionals, like The Arab American News Publisher Osama Siblani, to publicly launch the organization as a collective effort.

This was no small feat. AAPAC as a vetting and campaigning organization has had tremendous successes since its inception. AAPAC-endorsed candidates like U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Detroit) have become mainstays in American mainstream political consciousness.

Hammoud is married to Mona Hammoud. Together, they have two sons: Mustapha (25) and Mazen (24).

Prior to the creation of AAPAC, candidates had relied on local nonprofits and other groups that couldn’t officially endorse them.

“Along with this (limitation), I noticed a phenomenon that I call the individualization of politics,” Hammoud said. “Individuals would endorse candidates in exchange for personal favors most of the time, even though we had a few who were involved for the good of the community but still at the individual level.”

“I found that individualized politics was not good because it allowed politicians to reward support with personal as opposed to community-wide favors which could address and advance the cause of the community.”

Hammoud sought the creation of an organization that could do politics, “officially, openly, and collectively.”

He drafted AAPAC’s first bylaws, which were based on collective decision making and gave representative power to the membership as a whole based on the principle of one person, one vote. All issues are debated and put up for vote. Candidates are interviewed for endorsements in meetings that are open to the community.

“The idea was that with collective decision making, personal interest would fade and make way for community interest,” Hammoud said.

Hammoud and other founding members also insisted on the involvement of Arab American women in the organization. Women have held important leadership positions in AAPAC to this day.

AAPAC’s bylaws also insist on representing all Arab American ethnic and national groups.

Hammoud stands next to Detroit Mayor Duggan at an AAPAC event

In 2001, Hammoud stepped down from AAPAC’s presidency to become a political candidate himself, in an effort to challenge the political power of then-Dearborn Mayor Michael Guido. Hammoud won the primary, but lost in the general election, after the events of September 11 brought about uncertainty and panic in Metro Detroit.

Nevertheless, his mayoral bid got nationwide attention and was in no small part a catalyst for future Arab Americans to realize their own political careers.

“Running for office was not the norm in the Arab American community in this area when AAPAC began,” he said of the social climate in the late 90’s. “There were Arabs running for office here and there, but no one was expected to run and win.

“Even those prominent in the community said it was too early for us. But if you wait for someone to pave the way, then no one will pave the way. AAPAC did a lot of that work by creating a certain culture in the community where Arabs understood the political resources available to them. We realized that we could campaign as American citizens and be part of the process just like anyone else.”

Hammoud is married to Mona Hammoud and together they have two sons: Mustapha (25) and Mazen (24).

1 Comment

Bob Ghannam

September 14, 2019 at 6:19 amKudos for writing a feature on Mr. Abed Hammoud . Please keep writing about individuals like Abed so the youth in our communities can be aware of the satisfaction of working for the betterment of a society desperate for real heroes.

Bob Ghannam