History has marched on since they arrived in the middle of the last century, seeking refuge for what they thought would be a few weeks, but staying for a lifetime.

Around them the Middle East lurched from conflict to civil war to peace and back again. But for Palestinian refugees in these camps, there has been little movement over decades — only their memories and hopes can travel freely back to lost lands.

Visited by photographers decades apart, time seems to have passed at a different speed in many of the Palestinian refugee camps scattered across Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza.

Change there has been, but limited in its ambition. Canvas tents in 1948 Beirut grew up to be cinder block homes. Beaches evolved into sunless alleyways.

And young women balancing clay water pots on their heads in 1950s Gaza became the grandmothers of a generation who today have taps in their homes, but still haul bottled water home because it is filtered and so safer to drink.

A key presence in these lives is UNRWA, the United Nations agency which provides services and protection to 5.5 million Palestinian refugees. Around a third — more than 1.5 million — live in 58 registered camps.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East — its full name — was created by the U.N. General Assembly 70 years ago to deal with the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees who had been driven from their homes or fled the conflict surrounding the birth of the modern state of Israel in 1948.

One of the descendants of that exodus — Najah Abu Reyala — has lived all her life in Beach Camp, the third largest of eight refugee camps in coastal Gaza.

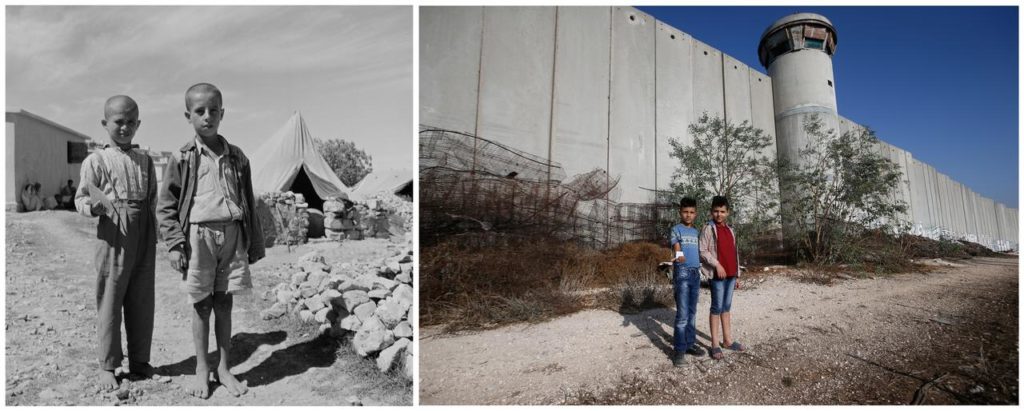

A combination picture shows Palestinian boys posing for a photo in Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, in this undated handout photo. UNRWA/Handout via REUTERS (L) and Palestinian boys posing for a photo in front of a section of the Israeli barrier in Aida refugee camp, October 19. REUTERS

A combination picture shows a Palestinian woman feeding a child at UNRWA’s re-hydration/nutrition center in Ein El Sultan camp in Jericho in the Israeli-occupied West Bank in this handout picture believed to be taken in 1960s. UNRWA/Handout via Reuters (L) and a Palestinian woman feeding a child at Sin El Sultan, September 17. – Reuters

A combination picture shows Palestinian school girls waiting in line to collect UNRWA prepared food parcels during the first intifada in the Gaza Strip in this handout picture believed to be taken in 1988. UNRWA Handout via Reuters (L) and Palestinian school girls waiting in line to collect snacks in a UNRWA-run school in the Gaza Strip, September 2. – Reuters

A combination picture shows nurses treating a child at an UNRWA health center for Palestinian refugees in Beirut, Lebanon in this handout picture believed to be taken in 1952. UNRWA handout via Reuters (L) and a Palestinian refugee girl receives a vaccination at an UNRWA clinic at Burj al-Barajneh refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon, June 23. – Reuters

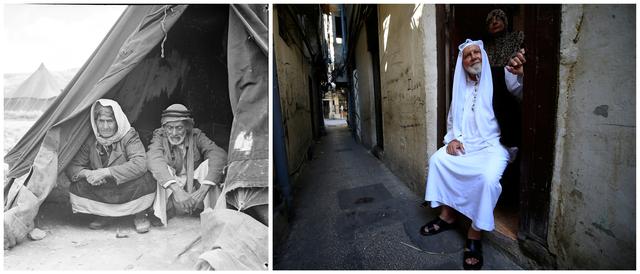

A combination picture shows Palestinian refugees sitting inside their tent in the newly formed Ein El-Hilweh refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon, in this handout picture believed to be taken in 1948. UNRWA handout via Reuters (L) and an elderly Palestinian man, with his wife standing behind him, poses for a photo inside their home at the Ain el-Hilweh refugee camp near Sidon, southern Lebanon, September 24. – Reuters

A combination picture shows a doctor examining a child in Baqaa camp, near Amman, Jordan, in this handout picture believed to be taken in 1969. UNRWA/Handout via REUTERS (L) and a doctor examining a child at a health center at Baqaa Palestinian refugee camp, September 29.

Now 61, she remembers the rudimentary conditions during her youth in the camp, where the population has grown from 23,000 to more than 85,000.

“Streets were not paved, they were sandy and dusty,” she recalled. But although the passing of the years brought more services, it also brought more tension, divisions and despair.

“Maybe they put electricity and water inside the houses, but things are far worse than they used to be,” she said. “Back then, we were more closely knit, we were more united.”

Abu Reyala and other refugees want the right to return to their families’ former lands in pre-1948 Palestine, lands which now lie inside Israel. Israel has rejected any such right of return as a demographic threat to its Jewish majority.

And many Israelis regard UNRWA — by far the largest humanitarian organization handling Palestinian refugees — with suspicion.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said that UNRWA’s longevity had served to perpetuate, not solve, the refugee problem.

“It is time (for) UNRWA (to) be dismantled,” he said in 2017, urging the U.N. to “re-examine” its existence.

Just such a re-examination is due in the coming days, with the U.N. General Assembly to vote on renewing UNRWA’s mandate.

Amid financial crisis and political uncertainty, Palestinian leaders warned of unrest if services were to vanish.

But in November 170 countries voted in committee for UNRWA’s mandate renewal ahead of the main assembly. Only two — Israel and the United State— voted against.

Although nothing is certain in Middle East politics, such an overwhelming majority is unlikely to be overturned in the final vote, the agency’s supporters say, with no easy alternative available.

“UNRWA’S detractors want a solution to the refugee problem without a political agreement,” said Elizabeth Campbell, an UNRWA official in Washington.

“And that’s a very difficult thing to achieve.”

Leave a Reply