— This article was written with generous support from the Education Writers Association’s Reporting Fellows program

There is little doubt that the Arab American community in Metro Detroit has made great headway in gaining political and economic security as it grows and evolves. Much of this momentum can be attributed to a culture of professionalization and educational attainment in Arab enclaves like Dearborn and Hamtramck.

So much so that this drive towards education has shaped the identity of the population over time. The community has grown outward from its working class immigrant roots to gain footings in the local and national political arena, medicine, law, the arts and more.

It is no doubt Arab families, like many other American families, hold education in high regards, just as its educational achievements affirm the thriving community’s hard work in building better futures for its generations. The demands of a competitive, globalized economy have made secondary and postsecondary education a need, like in any other American community.

Data tells the story

A look at some numbers highlights the community’s continuing and increasing success. It remains tough to get data on the Arab population through the census; the U.S. census does not provide an Arab racial or ethnic category, historically leading to Arabs categorizing themselves as White. But cities like Dearborn and Dearborn Heights are increasingly visibly Arab, and the American Community Survey estimates shows the heavy influence of immigration on the city’s population in the last few years.

Above: Click on the year on the bottom right hand corner to switch between yearly data. Source: Data USA

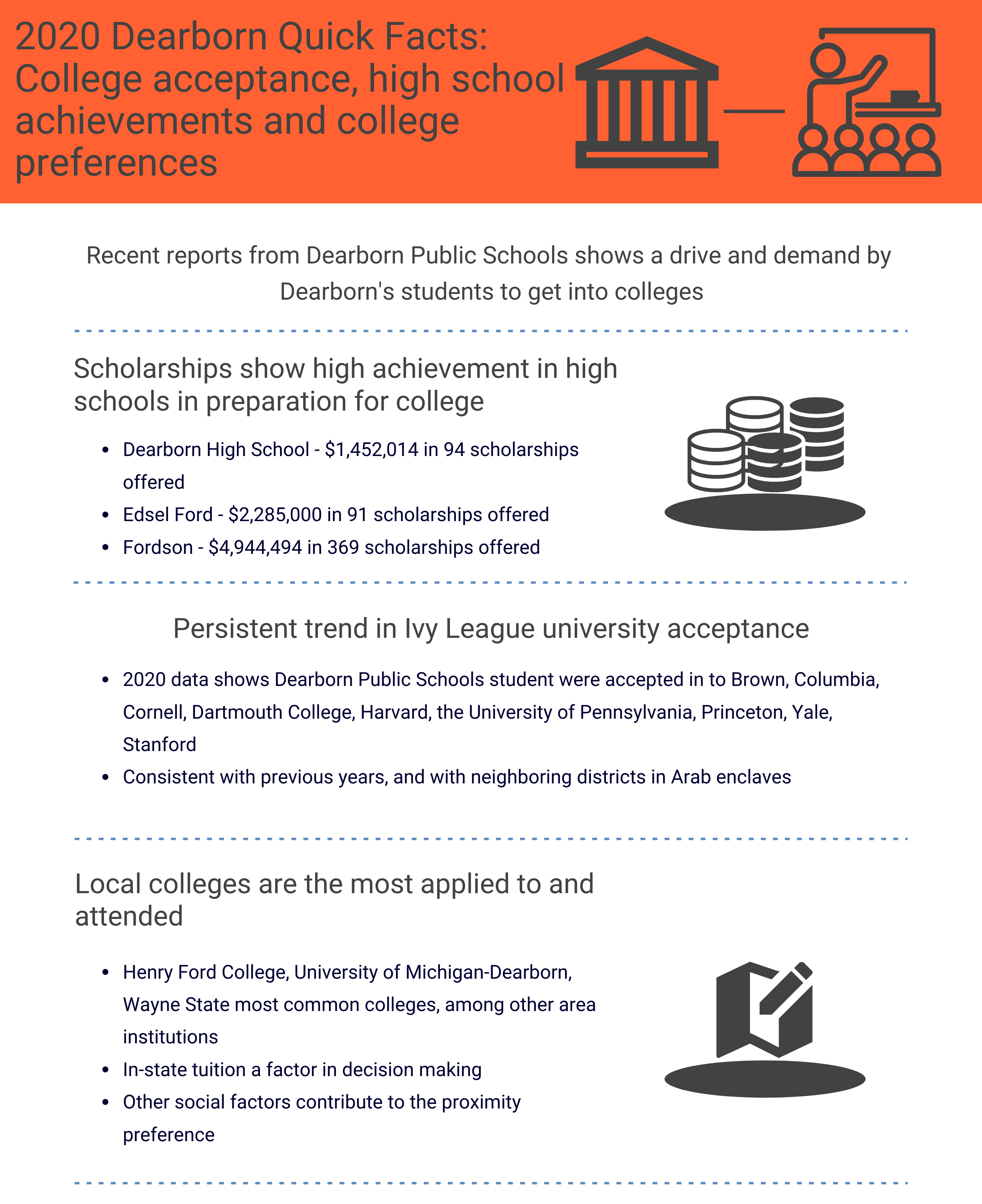

School districts where the Arab population has grown exponentially over the last few decades have shown impressive growth in statewide rankings, college acceptance and scholarships.

Dearborn Public Schools have been selected for the U.S. Department of Education’s National Blue Ribbon Schools awards five years running. Graduates from Crestwood High School in Dearborn Heights earned some $16 million in scholarships and awards in 2018 and almost $14 million the previous year.

Just in 2020, a year marked by unique educational difficulties due to COVID-19, 577 scholarships totaling some $8.8 million were offered to the Dearborn high schools and early college programs, according to numbers collected by the Dearborn Public Schools district.

A demand for a college education and acceptance into the country’s top universities has become a common phenomena in these heavily Arab populated districts. Last year, like years before, students from the district’s schools were accepted into highly competitive universities like Yale, Brown, Cornell Harvard, MIT and more.

71 percent of graduates from Dearborn’s schools enroll in a college within six months.

Dearborn schools quick facts sourced via Dearborn Public Schools. Image: The Arab American News

But the data also gives a glimpse into college preferences for many Arab American students and indeed their families. As a significantly immigrant community, the need to stay connected within the local area is a factor in deciding where to apply for college, for many students.

Many students take advantage of the area’s well known universities. Reports from Dearborn schools show most of the common colleges for graduates to enroll in are within the Metro area, including Wayne State University, Henry Ford College, University of Michigan-Dearborn or campuses a little further away like the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Eastern Michigan University and other state schools.

The costs of attending colleges further away, especially out of state, is most definitely a factor in why many students choose local colleges and Dearborn is no exception to this trend. But that pattern also speaks to often unspoken expectations that many Arab families have for college-aged children to remain in close-knit networks in the area.

Family ties, college needs

While social expectations and economic demands have produced a real need for the area’s immigrant population to strive towards education attainment, for young Arabs, especially young women, things have not always been simple.

A complicated and ever-changing relationship between the present-day needs of younger generations to pursue education has often come head-to-head with cultural and religious standards of what womanhood entails for some families, especially when it comes to the prospect of moving away from home to pursue degrees or to make future decisions based on personal needs and autonomy.

Though it is clear that second-generation men and women have broken the mold several times, expanding their academic interests or gaining real foothold in the Ivy League world, many can thank the determination of women who have had to negotiate and make their way through undue pressure to carve out an educational journey.

Those stories remain largely untold in local media accounts, though they are common knowledge and topics of conversation in the community itself. A community that has certainly evolved and made progress on issues of gender autonomy, but the persistence of young women to gain autonomy over decisions that affect them is essential to this progress.

The pressure has come in several forms. But there are often familiar details: A young Arab American woman is expected to stay close to home and often marry and raise children, either while maintaining an educational or professional career or at its detriment, if need be.

Parents may think it essential for their daughters to become homemakers as soon as they are able and can ignore the material reality of the difficulties and challenges of college, or their children’s own needs.

And most often, meeting those parental expectations means finding educational institutions close to home, thus the popularity of commuter colleges in the area.

Such is the story of a graduate student who agreed to speak about her experience on conditions of anonymity. Hailing from a strict and conservative Dearborn family, the student’s educational identity has been shaped by experiences with the cultural expectations of her parents and others, and the way she has asserted her independence in the face of them.

“Growing up, there weren’t as many women, at least in my family, that I could look to as a precedent for educational pursuits,” said the student, who graduated high school in the early 2000s. “I was a high achiever in high school, but sadly I didn’t have specific aspirations. I was a dreamer, not a planner, because I really didn’t know if I would have an opportunity to pursue my education in the future.”

In those years, she said she didn’t know if her family was or could be different. In high school, she began to notice a spectrum of strictness and diversity of what students’ futures would look like.

Late in high school, the idea of marriage was introduced to her. Being a high achiever, she did apply to schools even with this expectation.

“I didn’t have the option to just do school; and when I look back at that now, I should have been able to focus just on that,” she said. “Instead I had to make it coexist with my family’s plan to get married and honor the traditional life path.”

When it came to planning for what colleges to attend, the student was restricted geographically. Her parents, like many in Dearborn, expected her to stay in the area where they lived or where her would-be husband lived.

“I did have dreams of going away for college, but I knew that was not going to be possible,” she said. “I applied to local schools.”

Her parents supported the idea of further education, but their priorities centered around learning housework and their goals for their daughters to raise families of their own.

The student said that having to juggle school and the responsibilities of a traditional marriage did in fact keep her from exploring and pursuing educational and career passions. It was hard to make either work, though she had to for some time.

I always had this fear of being ostracized and had to step carefully, but I knew I had to do what’s best for me because I’ve done so much their way and it very rarely turned out to be what I also wanted.

“What I’ve learned from that experience, and what I would like others to know, is that at that young age you’re not an adult, by any measure, and you shouldn’t have to make adult decisions where yours and possibly another person’s future is on the line,” she said. “Maybe those were expectations that my parents were used to, but I didn’t feel right about it. And the more I learn about the world, the more I am against that concept. You shouldn’t have to make those decisions for yourself and no one should make them for you is they’ll be that life altering.”

The student pointed to a disconnect between such priorities — which in themselves can be a healthy part of life for many, but are forced on many at too young of an age — and the material reality of navigating through the modern American secondary educational system.

Negotiating these worlds and maintaining their family’s trust can also affect the types of educational fields many young Arab women choose.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing how that dynamic geared my educational preferences, but I also had to make decisions along the way that weren’t the best for me,” the student said. “They came from an escapist mentality; I was trying to escape a lot of pain.”

Decisions over graduate school were at least in some part made to seek some autonomy, while assuring her parents that the field she chose could land her financial stability, not to mention giving them the pride of a post-secondary title.

Her perseverance has led her to make some real positive changes in her life, including pursuing grad school. The student knew that for her to take this chapter of her education seriously, she would have to prioritize her needs over the cultural desires of her family.

“I always had this fear of being ostracized and had to step carefully, but I knew I had to do what’s best for me because I’ve done so much their way and it very rarely turned out to be what I also wanted.” she said. “We didn’t have common interests, we didn’t share the same world view, except for the idea that family matters.”

Now she hopes that her parents will see the outcome of her decisions and, aside from their initial objections, be happier for it.

Cultural demands shape education identity

A somewhat similar struggle played out in the Arab enclave of Ypsilanti. Layali, who chose to keep her last name off the record, went to a private Islamic school and had much of her educational future already sketched out by her father.

Layali’s father, himself an educated Arab immigrant with multiple graduate degrees, held education in high esteem. But like many other Arab parents, his children had little choice but to attend an area college.

“I knew I had to stay in the area,” she said. “The thought of an opportunity to maybe go somewhere else didn’t even arise. I went to college right behind my parents’ house in Ypsilanti.”

Layali didn’t think it worth it to seek college elsewhere, let alone a full campus experience in nearby Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan.

“It was the way my family worked; I knew I had to be home at a certain time, I knew that my dad carried his image in a certain way,” Layali said. “Going to a campus outside of town would have meant driving, on-campus living, there’s a life that’s attached to that kind of campus. I knew I wouldn’t have been able to engage.”

Layali also chose majors in college that fit her father’s desires for a very popular Arab American field: Law. Her first choice, writing and journalism, weren’t considered career-worthy to her father.

Going to a campus outside of town would have meant driving, on-campus living, there’s a life that’s attached to that kind of campus. I knew I wouldn’t have been able to engage.

But Layali’s story also shows the wide spectrum of needs and educational needs of Arab families in the region. Her father put college in front of any expectations for his daughter to get married, though that was certainly something he expected of her after that education was complete.

“Although education was held with such high regard, it still was because I would have my own degree when I marry so the expectation was still there,” she said.

Her father’s work in the community also facilitated this need. Getting a secondary education and building networks and footholds in the economy and sociopolitical fabric were seen as a way to empower the immigrant community, particularly the intra-Arab ethnic group Layali’s father represented.

“My dad was very adamant about us not getting married right away; he wanted us to get an education, but that education had to be according to him,” she said. “That was a little different from the majority of my extended family, the few cousins I have here. We weren’t even speaking about marriage until I was in college, which was quite late for a lot of (my community’s) women and the Arab diaspora community in general. It wasn’t even brought up; we brought the topic up.”

Layali said that she wishes she had been given a different perspective or a different lens of possibilities for what colleges were available to her. She also said she feels college was encouraged due in large part to a certain public image her father adhered to and that credit for her college accomplishments was co-opted by him.

It wasn’t until she pushed certain boundaries that marriage was introduced as a concept. Switching majors away from law school and expanding her social life brought up anxieties familiar to many Arab parents. Her father thought giving Layali the option of marriage to whomever she chose could be a way to quell her rebelliousness.

Layali did eventually make the tough decision to apply to graduate school out of the state and was accepted into two highly competitive masters programs, one with a generous scholarship. Though she wasn’t allowed to attend initially, her father eventually relented.

Reflecting on her unique college path, Layali said her internality behind her college decisions did leave an indelible effect on her relationship with her father, and with her broader community. Her educational identity, like many others from her generation, was shaped by negotiations between cultural expectations and the need for autonomy.

Positive shifts

“In the Arab community, there is a huge emphasis on college, equating to success,” a longtime counselor at Dearborn schools said.

The counselor, who chose not to share their name for this article over matters of trust with their students and their families, said that the need has intensified over time and that Arab students are preparing early in school for college careers and increasing competition within the community itself to get into commonly desired schools.

But the counselor also spoke of progress in terms of college decisions for her Arab students, with family input over what they should study and where waning as a major factor over time.

“I do see a lot more intrinsic motivation,” the counselor said. “I used to hear students say, ‘my parents said I need to do this’ or ‘I’m choosing a college or career because my siblings did, too.’ But now, I’m seeing students needing to excel and know what they need to do more than ever before, and they’re trying to do it.”

The counselor said part of the draw for Arab students in shooting for the local public-ivy, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, is that it carries the extra advantage of being close enough to home.

The push is definitely for education… the students and their families are all about education

Going to an out-of-state college is also cost prohibitive for many families and that cost is indeed a major factor in college preferences.

Most notably, the counselor said that though they may have heard of cases in years past where female students were asked to prioritize certain cultural expectations, this is not something they typically see.

“The push is definitely for education and I think that has progressed from a decade or two ago,” the counselor said. “The students and their families are all about education.”

The counselor said there is still a little resistance from parents when it comes to the prospects of their children moving out of state for college, but that has also evolved over time.

“Some parents may ideally want students, both male and female, to stay closer to home and try and excel at their college aspirations,” the counselor said. “But if moving means a better degree, a better opportunity, I do believe I am seeing more families that are allowing students to move away.”

Leave a Reply