By Nikhil Misra-Bhambri

Most visitors to California, “The Golden State”, are unfamiliar with the large swath of barren farmland covering the state’s entire interior. Among the hardy immigrant laborers working the farms in the interior are a group of men from Yemen who started arriving in the 1950s to flee their nation’s turbulent political situation. They endured strenuous work conditions in the vineyards, economic inequality and challenging living situations to support their families back at home. Although largely hidden among the vast farmland, these Yemenis strive to maintain a small commercial and religious presence in the San Joaquin Valley.

Neama Alamri, a historian currently working on a book on the history of the Yemeni diaspora, describes in her article titled “The Politics of Living and Dying” how the Middle East was faced with growing Arab nationalism in the 1960s. In 1967, the National Liberation Front in South Yemen declared a Marxist state and a year later, in 1968, the monarchy in North Yemen was overthrown and the Republic of Yemen was established. The decolonization in the South and revolution in the North resulted in a rapid deterioration in the region’s economy and the labor force became the nation’s largest economic export. Many young men sought work opportunities in the Gulf and the United States.

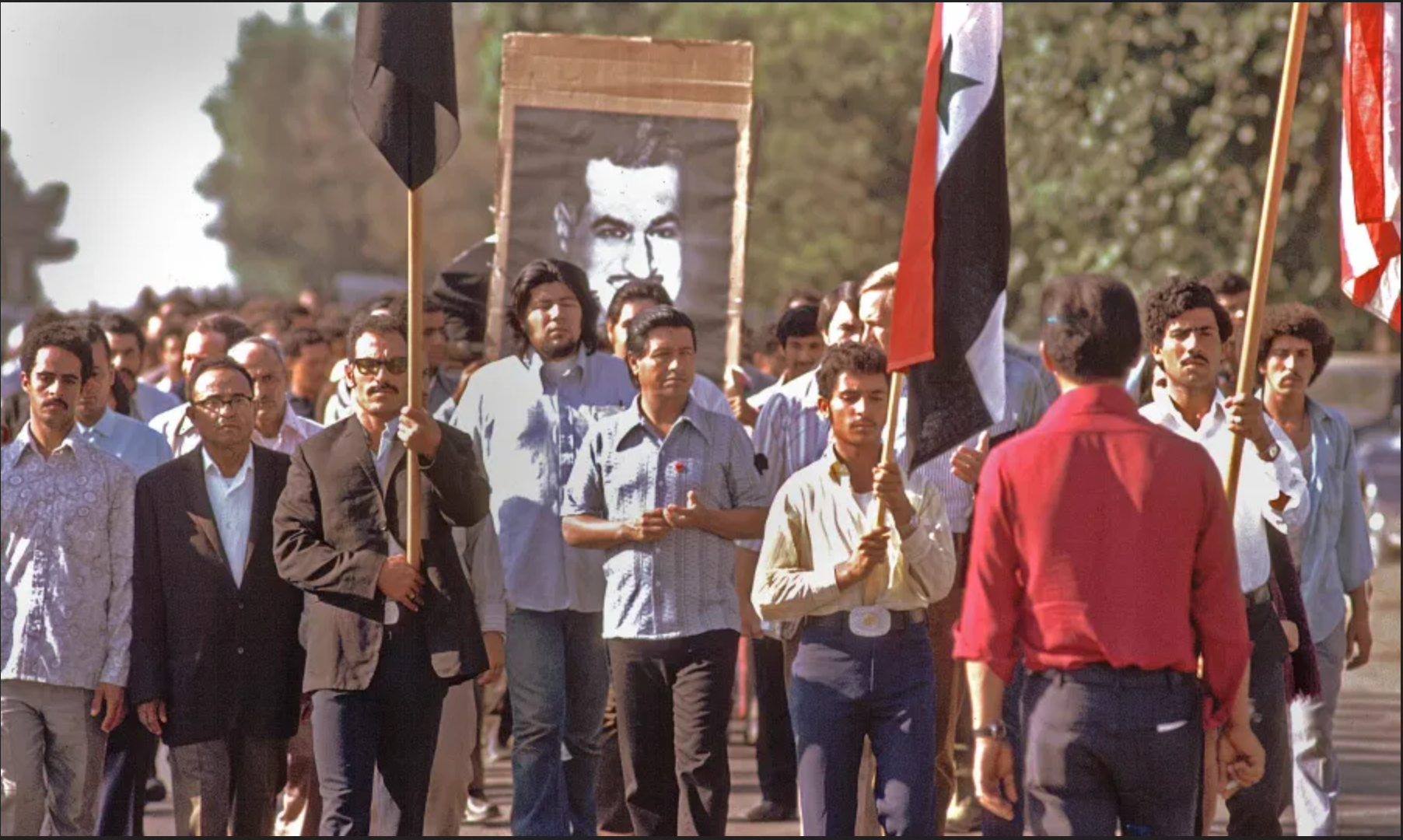

Chavez, center, marching with Yemeni activists, Delano, CA, 1973. – Courtesy of Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

A fascinating video by Middle Eastern American Resources Online (MEARO), “The Last Harvest”, shows how most Yemeni immigrants in the United States found work in Detroit’s factories, while roughly 5,000 men from the rugged Ibb region in the nation’s interior ventured out to California’s San Joaquin Valley for agricultural opportunities. Commonly regarded as the “Food Basket of the World”, the San Joaquin Valley produces 12.8 percent of the nation’s agricultural goods, including grapes, walnuts, oranges and vegetables. Drawing upon their knowledge of farming from Yemen, the strapping Yemeni men gained employment on the various vineyards and agricultural fields dotting the valley.

Mohamad Abdullah, featured in “The Last Harvest”, was a success story among the early pioneers. He came to the United States in 1956 and resided initially in Pennsylvania before he moved to Delano, California in 1962. In Delano Abdullah began working at Sunview Vineyards, one of the leading growers of grapes in California. Abdullah stated, “my hobby, you know, was the farm because I was born and used to live on a farm in Yemen. It is hard work, but I love it.” He began as a grape picker for three years before becoming a crew boss and eventually supervisor. By the end of his career, Abdullah served as a chief foreman, in which he supervised hundreds of workers, mostly Latino and some Yemenis.

Yemenis faced several obstacles as they strived to earn a decent income. In an environment of low wages, language barriers and limited access to health care and social services, Yemenis were considered more desirable workers compared to Mexicans and Filipinos, who were organizing themselves in unions to demand better work conditions

Ali Abdullah Jr., the grand-nephew of Mohamad Abdullah

Alamri explains in “The Politics of Living and Dying” that, as farm workers, Yemenis faced several obstacles as they strived to earn a decent income. In an environment of low wages, language barriers and limited access to health care and social services, Yemenis were considered more desirable workers compared to Mexicans and Filipinos, who were organizing themselves in unions to demand better work conditions. In her article “Yemeni Farmworkers in California”, Mary Bisharat interviewed various workers, most of whom earned $2.30 an hour and had a tax rate of 20 percent. Furthermore, busing to and from the barracks to the vineyards cost $3 each way.

In “The Last Harvest”, Ali Abdullah Jr., the grand-nephew of Mohamad Abdullah, remembers his days helping his family with picking and packing grapes.

“A typical day would start by getting up at 4:30 a.m. to get ready to be at work at 5:30,” A former high school teacher mentioned. “All my Yemeni students worked in the fields; they sometimes got up at 3 -3:30 a.m. to work in the fields before school. They had to often skip eating and showering before school. This dedication to school made teaching a very positive experience.”

Initially, many Yemeni laborers resided in labor camps scattered throughout the San Joaquin Valley, often miles outside a city. In his article “Yemenis in San Joaquin”, Ron Kelley explains how living conditions were extremely spartan and cramped. Sometimes two or three men shared a small room, while in “barrack” type camps, a dozen or more would stay in a larger area. Employees usually deducted money from the worker’s paycheck in order to cover expenses in the camps. Bisharat mentions how, “488 of the farm labor camps in California failed to meet the state’s housing, safety and sanitation standards in 1974.”

Ahamed Yahya Masherah’s 1972 AFW ID card, which he still carries to this day. He worked with and was a friend of Naji Daifullah in Kern County. He now lives in San Francisco. Nagi Daifullah was shot and killed August 15, 1973 by Kern County, California Sheriff’s deputies during the grape strike with Ceaser Chavez’s United Farm Workers. He has been honored by union organizers with the San Francisco Janitors. Photo: Eric Luse/The Chronicle

During these early days, Yemenis strived to retain their practice of Islam as their anchor during these difficult times. According to Bisharat, the workers “[did not] observe the fast of Ramadan because of the arduous nature of their work. [However,] they prayed five times a day in the field and attend[ed] the mosque whenever possible.” They also avoided all habits deemed haram (forbidden), such as drinking and smoking.

In response to ongoing harassment and arrests, some Yemenis joined the United Farm Workers (UFW) movement, founded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Nagi Daifullah, a 24-year-old Yemeni immigrant, was a key leader in the UFW who began his involvement during the 1973 grape farmers strike. He successfully transcended linguistic and ethnic backgrounds for his mission in uniting fellow farmworkers around a shared cause. Cesar Chavez stated, “He often served as an interpreter at union functions and gave himself fully to the grape strike and farm worker justice.” Unfortunately, his efforts on his fellow workers’ behalf resulted in his death at the hands of three Kern County police officers in August 1973. Today, in the midst of ongoing racial and economic discrimination, Daifallah’s legacy lives on as he inspires immigrant workers to stand up for their rights and demand equality.

The late 1970s were the final years of Yemenis’ hard work in the San Joaquin Valley’s vineyards. At this time, many of them moved to Michigan or went back home to Yemen to reunite with their families

Funeral ceremony for martyr Nagi Daifullah. Courtesy of Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

The late 1970s were the final years of Yemenis’ hard work in the San Joaquin Valley’s vineyards. At this time, many of them moved to Michigan or went back home to Yemen to reunite with their families. Those who remained in the valley had saved enough money from the vineyards and moved into apartments or bought homes in Delano. Today, Mohamad Abdullah spends his time between his family in Yemen and his Latino wife and children in the San Joaquin Valley. He describes in “The Last Harvest” how he used his hard-earned money to build a new, large home in Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, where he spends time with his family and friends.

Nora Abdullah, Mohamad Abdullah’s daughter, is immensely grateful for her father’s effort to pave the way for his children to live the American dream. She is quoted in “The Last Harvest.”

Mohamad Abdullah with his wife, Irma, daughter, Nora, and son, Audie

“The fruit of my father’s labor not only provided material success. The grapes also changed the lives of his children. He is very proud of the fact that he was able to send my brother and me to college. From his hard work and sacrifice, we were spared the labor of the field.”

Most of the few hundred remaining Yemenis in central California have bought convenience stores and markets scattered throughout the region. Alamri said that over the years, “Many have expanded from small corner shops to larger grocery shops selling produce. Since the 1970s, the community has been able to economically flourish through these small businesses that they are opening in the same places where many of them worked originally as farm workers.”

Delano is home to Elmers, a fast food halal burger restaurant owned by the Obeid family. The menu at Elmers reflects how Yemeni Americans have developed a taste for typical American fast food, while also staying true to their Muslim roots. One of the sons, Salah Obeid, states in “The Last Harvest”, “[my] personal favorite [burger] is the bacon cheeseburger. Being Muslim we cannot eat pork, so ours is pure beef.”

While many current generation Yemenis have high aspirations, they remain indebted to their parents for their sacrifices made while slaving in the fields. In gratitude, the children sometimes put their own dreams on hold to help their parents’ continued success in business

Kais Obied

While many current generation Yemenis have high aspirations, they remain indebted to their parents for their sacrifices made while slaving in the fields. In gratitude, the children sometimes put their own dreams on hold to help their parents’ continued success in business. In “The Last Harvest”, Kais Obeid, son of the Elmers’ owner, said, “I got straight A’s in high school and acceptance to UC Berkeley. However, I decided to [stay] here, because I wanted to stay close to my family. That is really more important to me than college. If I lose my family, I lose everything.”

Rakan Salah, whose parents own Fastway Market in Richgrove, speaks about his commitment to his family’s continued well-being.

Rakan Saleh

“Being in the store business is just work, work, work. There is not that much free time. When I was in high school, I would just go to school, get done and come back and work. I would do my homework [in the store] during evening time.”

In addition to economic success, the San Joaquin Valley’s Yemeni community strives to preserve their Islamic teachings and instill them in future generations. They were essential in founding the local masjid and religious school, Abu Bakr Al-Sadiq Mosque and Madrassa, located in Delano. The center is a popular gathering place for Yemenis during Ramadan, Eid and other festive occasions. It is frequented by the youth on weekends, where they are taught Arabic and learn about the five pillars of Islam.

Today, in the midst of their homeland’s ongoing wars, many Yemenis fear for their families. Alamri states, “Since 2015, the war in Yemen has caused the influx of Yemenis in the Central Valley to grow immensely.” An article by The World, “For One Yemeni American, the long wait to bring his family to Safety”, describes the fears of Saber Askar from East Porterville. During the first year of the Trump presidency, Askar was worried for his wife and daughters in Yemen, who had difficulty getting their American visas processed after Yemeni immigrants were banned by the U.S. government.

Abu Bakr Al-Sadiq Mosque and Madrassa in Delano, California

These few thousand men in central California were bold pioneers who had a vision to transform the lives of their families despite punishing work conditions, discrimination and economic injustice

“They cannot find enough food to eat and every week it is getting worse,” he said. “They make me bleed inside every time I talk to them. I do not know what to do. Every time I call, I am afraid they are not going to answer anymore.” Thinking back to his fellow countrymen’s struggles to attain the American Dream, Askar softly said, “insha’allah”, with the hope that his wife and children will soon be able to join him in the land of opportunity, the U.S.

“With everything that is happening politically in Yemen and the USA, Yemeni Americans are longing for history of their previous migrants and diasporic experience to contextualize what is happening now,” Alamri said. “We want to say that we are not foreign to the Central Valley, as it has been our home for decades. The history of farm workers is demonstrative for that and also illustrates contributions that Yemenis have made to California and American social history.”

The rather “unknown” Yemenis of the San Joaquin Valley are true success stories of the American Dream. These few thousand men in central California were bold pioneers who had a vision to transform the lives of their families despite punishing work conditions, discrimination and economic injustice. Although many of the youth have the opportunity to leave the valley, they have not severed their umbilical cord attached to the grapes of the vineyard. Instead, they stay and help with their family businesses. As a consequence, the Yemeni community continues to maintain a commercial as well as religious presence, as they live up to the legacy of their sojourning forefathers. Bisharat wrote, “The pride of the Yemeni and his sense of duty and loyalty have sustained him in the past and provided the goals which help him transcend his contemporary existential hardships.” The Valley’s Yemeni community continues to embody these principles.

– Nikhil Misra-Bhambri is a freelance jouranlist based in California. This article is special to The Arab American News. All photos are videograbs from “The last Harvest” video

Leave a Reply