Private First Class Peter Essa, a Chaldean American and World War II veteran, seemed to have unknowingly carried a piece of World War II with him for the last 78 years. Wooden fragments from the bullet he was shot with in the invasion of Normandy were found in his ankle two months ago after he visited a doctor because of a swollen ankle.

Essa was drafted into the war when he was just 18-years-old, having to leave his mother, father and six sisters. He was born in the United States in 1925 after his parents immigrated here from Iraq. His mom came to the United States in 1908 and his dad in 1914.

He received a letter in the mail informing him of his required service in the war. He said he just pictured himself joining the army and was unaware of the fact that they would eventually end up in active combat.

He said his family was both worried and slightly happy he was leaving home.

“I think they wanted to get rid of me, really,” he joked, knowing his sisters were getting a break from his bossiness.

Following his summoning into war, he then had to report for training along with other soldiers who’d been drafted. His first training base was Fort Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan, where he trained for two weeks before moving to Camp Van Dorn in Centreville, Mississippi. He said he was there for 11 months before the recruit training in Fort Meade, Maryland. His last training stop was Camp Shanks in Orangeville, New York, which was actually named “Last Stop USA.”

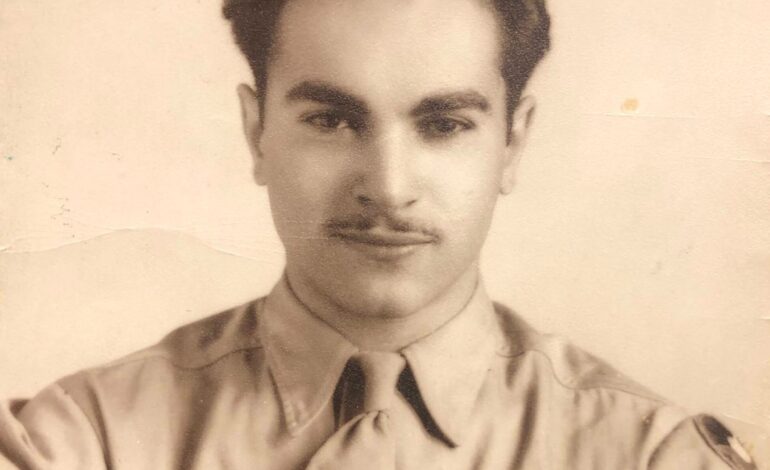

Essa pictured with his rifle during training at Camp Van Dorn in Mississippi.

Photo courtesy of his daughter, Teresa Essa

Camp Shanks was an embarkation camp that trained soldiers at their “last stop” before they were shipped to Europe for battle. Essa and the other soldiers then departed for Europe on the SS Luxembourg that he said he thought was shipping them to a new training base.

“We didn’t know there was an invasion coming, that’s all a secret,” Essa said when recalling the trip over to Europe.

Upon arriving in Europe, Essa recalled a large ship coming into the harbor near the ship he was aboard, where he saw General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of the Allied forces, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill preparing to give orders. Essa said they began to speak to the soldiers over a loudspeaker about an invasion and that’s when they knew something serious was coming.

“We knew something was going on when they said God bless you all and good luck,” he said. “We knew something’s happening.”

They were preparing for “Operation Overlord”, also known as D-Day; the invasion of Normandy, France that commenced on June 6, 1944. Essa said this was his first day in combat and unbeknownst to him, the invasion in which he would be shot and wounded.

Soldiers were transferred to smaller landing crafts that took them closer to the shores of Normandy, where German troops were stationed in the distance. Essa said that as they reached the shoreline, they were dropped from the landing crafts into water up to their necks. With their rifles over their heads, he said they trekked through the water to reach the beach.

“We’re in the water up to our neck, we’re crawling to the beach and when we got to the shore I remember we crawled quite a ways,” he said. “The enemy wasn’t there; the enemy was a little ways away firing guns and bombs and everything.”

As they crawled, he said, all they saw was ceaseless firing coming their way. They dug up foxholes to shield themselves from the enemy’s attacks as the Germans fired from and hid in the trees.

“Every time we heard a big blast, we had to get down into the foxholes, into the ground,” he said. “That’s the only thing that protects you. Dig your holes or you’re taking the chance of getting killed.”

He said they had to wait for orders to engage and finally charged into combat, where they began fighting back on Omaha Beach in Normandy. And if a soldier got wounded, he said that First Sergeant Durham told them they must keep going.

In the midst of fighting back, Essa was shot by a German wooden bullet in his left ankle. He immediately screamed for help and stated that the pain was so immense that he believed he would not make it.

“When I got shot, I thought I was killed,” he said.

Sergeant Durham carried Essa on his back to safety, where he was then taken by jeep to a field hospital and treated by the medics. Unfortunately, that sergeant was killed in combat shortly after, Essa said.

Essa recalled his experience on the jeep among other wounded soldiers and thought they would not make it to safety.

“I can’t believe I’m tied up on a stretcher above a jeep, and I can see bombs going by. So we just figured we were going to get killed.”

The medics treated him at the nearest field hospital and he said that maggots were also used to quickly kill the germs present in his wound.

The severity of his injury required him to be transported to another field hospital in England, where he was treated. He said he vividly remembers that picture of blood and bodies he saw then.

“That’s all you see is blood all over the place,” he said.

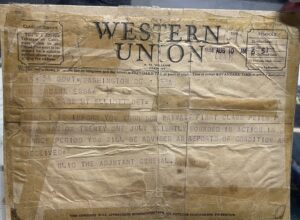

His mother received a telegram informing her of his wound and was told she would be informed of any updates.

This is the telegram Essa’s mother received informing her that he had been wounded in the war.

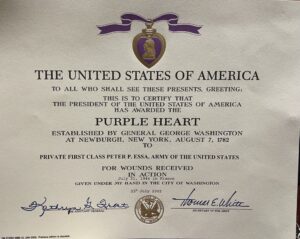

Following his treatment in England, he was then sent to Crile Military Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. Here, Essa went through a total of six surgeries and was awarded the Purple Heart. He set the scene of being awarded whilst sitting in a hospital bed and still recovering from being shot.

He was officially discharged from the war in 1945 as his injury was too severe for him to return.

Essa’s Purple Heart certificate he was awarded after being wounded in World War II.

His life post war of course looked much different than going into active combat. He used the GI Bill, which helps World War II veterans pay for school, and attended a butchers school. He then took a trip to Iraq in search of a wife. He then married a woman named Samira, from Baghdad, and moved her to the States, where they had five children.

Essa was also awarded the Bronze Star for his service and his wife recalled two soldiers appearing at their house in Metro Detroit asking for him. She said they saluted him as soon as he came to the door, and that alone brought her to tears.

78 years later

Last November, Essa said he noticed pain and swelling in his left ankle, where he’d been shot 78 years earlier. He then went to the doctor and discovered that the wound site had to be cleared of pus.

Essa said that as the surgeon was cleaning out his wound, he started pulling wooden fragments out of his ankle with utter confusion as to what what those pieces could be. He then informed the doctor that he’d been shot with a wooden bullet in World War II.

“He couldn’t believe what he was seeing,” Essa said about the surgeon’s astonishment.

For 78 long years Essa has carried a piece of the war with him from the day he was shot in the invasion of Normandy, but is fortunately now relieved of the pain that bullet cost him.

Leave a Reply