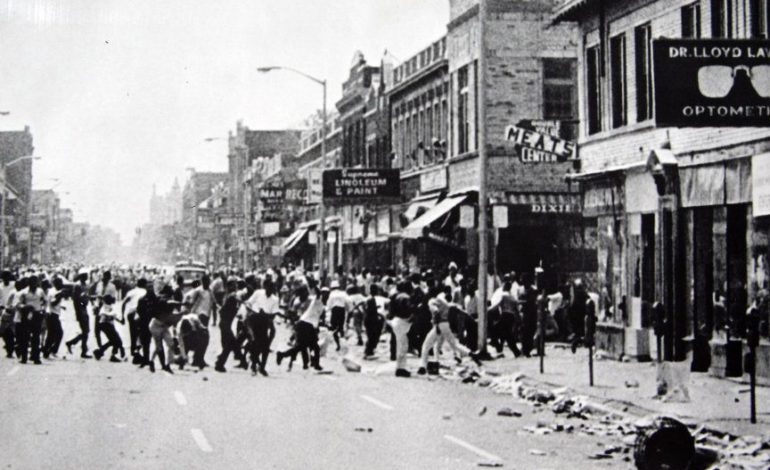

DETROIT— In the dark hours before sunrise on Sunday, July 23, 1967, no one knew that Detroit would be ablaze for the next five days , leaving countless citizens injured and 43 dead.

The summer of 1967 changed Detroit forever.

Before any looting, arson or fighting began that day, the Detroit Free Press reported that an undercover police officer went into an after-hours pub early Sunday morning. Roughly 85 customers from the bar were arrested and civil unrest began to increase around that time as angry residents poured into the streets.

Many Arab Americans lived in the southend of Dearborn and some were scattered about Detroit at the time of the uprising. Although the Arab population in Metro Detroit has risen greatly since 1967, the impact of the rebellion has been felt since then.

Business owners defend their shop with rifles during the 1967 riots

During the late 1960s, the Arab American community in Metro Detroit was at a crossroads, according to Ismael Ahmed, senior advisor to the chancellor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and co-founder of ACCESS.

“That general period was during the 1967 war [June war],” Ahmed said. “Also, a period of the fight against colonialism in the Arab world for national identity and pan Arabism. The Arab American community was made up of immigrants and Arab Americans. Arab Americans had tried for a really long time to assimilate.”

Ahmed added that the Arab American community was not entirely successful at assimilating.

“During that period we saw roots of our community,” he said. “There was lots of debate in the community about where we stood, what color we were, what does all this mean.

“For me and a lot of Arab Americans, we were affected by the period, the anti war movements, civil rights movement, urban renewal fight in Dearborn, all that had a fairly radicalizing affect which would later result in change in organization and activity by Arab Americans. It was still nascent.”

Ahmed said the 1967 civil unrest had tremendous impact on the Arab American community and that many Arab American organizations were established in response to the uprising, such as the Association of Arab American Graduates (AAUG) and ACCESS, as well as many national organizations.

“I think its really important that we help understand that this was not a riot,” Ahmed said. “It was a rebellion. They [rebellions] are about something.”

One big misconception about the uprising is that Detroit started losing residents after that event.

“People had already been leaving,” said Dr. Sally Howell, an associate professor of history at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and director of the university’s Center for American Studies.

At the ready, a national guardsman from Michigan stood by while fireman dealt with the fires during the 1967 uprising in Detroit – Photo by AP

She also said the Arab American community was at the cusp of big change with the new immigration laws of 1965; quotas were lifted and more people could come to the US to study, work and be reunited with their relatives.

“It wasn’t just the uprisings that began the change,” Howell said, adding that the structural changes and the conflict in the Middle East worked together to greatly impact the Arab American communities.

“To a large extent, the Arab American community at that time was not politically seen in the same way they are today,” Howell said. “There was no central Arab American establishment, like there is now. Arabs weren’t on the front page of the news; the conflict in the Middle East wasn’t on the front page like it is today. The Arab American community existed within the White community here. They weren’t seen as different from Whites. Some people were politically active. Some were in solidarity with African Americans.”

Howell also said that Dearborn Mayor Orville Hubbard was a segregationist and he used the uprisings as an opportunity to reinforce segregation; he wanted Dearborn to be a White city.

Edward “Ed” Deeb, an American of Syrian heritage who has been involved in many facets of the Detroit community in servitude of others for decades, witnessed the civil unrest of 1967.

“We have to understand that many of the people from Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and all Middle Eastern countries who came here, they didn’t have anything,” said Deeb, who was president of the Michigan Food and Beverage Association in 1967. “So, they opened up these stores with very little, just to eke out a living.

Deeb said the Arab American and Chaldean-Iraqi communities were able to improve after the mass exodus of the large food and beverage chain stores due to the civil unrest of 1967. The Arab Americans and Chaldean-Iraqi communities acquired the larger markets; they could improve their stores and make their companies more attractive, since the big companies had left town.

“Frankly, what we did was we encouraged all the people in the food industry to help bring Detroit back to a peaceful nature,” Deeb said.

Edward Deeb was the President of the Food and Beverage Association at the time of the Detroit uprising, and is the founder and chair of the Michigan Youth Appreciation Foundation

Deeb said companies like Farmer Jack, Great Scott, A&P, Kroger and Chatham left the city. This mass exodus of big chain stores left the balance in the place of small shops and convenience store owners; many small businesses were owned by those Arabic and Chaldean-Iraqi heritage.

At the time of the rebellion, Deeb kept a call log of problems the food and convenience stores were facing and he and some colleagues were subpoenaed to appear in Washington, D.C to share the damages that were done to the shops. He shared his plans for using this log to help improve the Metro Detroit community and he continues to use what he observed from the 1960s to help others to this day.

Deeb’s community service in Metro Detroit led him to be a recipient of numerous community service awards. He also received a Point of Light award from former President George H. W. Bush.

Deeb’s Michigan Youth Appreciation Foundation and annual Metro Youth Day event have been impactful components of positive changes in Detroit. The youth event celebrated its 35th year on July 12; it gives young Detroiters the opportunity to learn about colleges, win scholarships, play games, gain access to mentorship and more.

The 50th anniversary commemorations of the 1967 rebellion have included multiple initiatives by Metro Detroit organizations to dispel myths and share personal accounts. The Detroit Historical Museum worked for two years to collect written and oral stories from people who witnessed the rebellion; there is an online archive and the museum opened its exhibition to the public in late June.

In addition, the Detroit Free Press launched a live twitter experience for people to relive the history moment by moment to show what it may have been like in the 1960s to have social media during historical moments.

For in depth accounts by citizens connected to Detroit, including Ed Deeb, visit www.detroit1967.org

This report is a part of The Detroit Journalism Cooperative, a partnership of five media outlets reporting on the city’s future after bankruptcy with stories that have never been told before—on-air, online and in the community.The Cooperative includes The Center for Michigan’s Bridge Magazine, Detroit Public Television (DPTV), Michigan Radio, WDET and New Michigan Media, a partnership of ethnic and minority newspapers.Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, The Ford Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the DJC partners are reporting about and creating community engagement opportunities relevant to the city’s bankruptcy, recovery and restructuring.

This report is a part of The Detroit Journalism Cooperative, a partnership of five media outlets reporting on the city’s future after bankruptcy with stories that have never been told before—on-air, online and in the community.The Cooperative includes The Center for Michigan’s Bridge Magazine, Detroit Public Television (DPTV), Michigan Radio, WDET and New Michigan Media, a partnership of ethnic and minority newspapers.Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, The Ford Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the DJC partners are reporting about and creating community engagement opportunities relevant to the city’s bankruptcy, recovery and restructuring.

Leave a Reply