By Frances Kai-Hwa Wang

MI Asian

“Before it was even called urban gardening, my parents kept a garden in the backyard ever since I was a kid,” said Shane Bernardo, a life-long Detroit resident and a consultant, facilitator and speaker actively involved in food justice. “So I learned at a very early age how strongly my family identified with our cultural roots and our traditional foods, and that informed how we identify as people in the diaspora.”

As food justice activism and urban farming make strides in Metro Detroit, Asian Americans add complexity to the food justice movement and interesting connections to larger issues. Asian Americans are often mistakenly stereotyped as the model minority and assumed not to have issues resulting in food insecurity. There is, however, a wide diversity among the Asian American community in Metro Detroit and a wide range of ways in which Asian Americans face food justice issues.

Asian Americans face challenges in sourcing culturally relevant foods, chronic health issues exacerbated by poor diet and cultural appropriation. Asian Americans are also doing innovative work with food and creating solutions in gardens.

The food justice movement is often understood to include issues surrounding food insecurity, food sovereignty and ethical growing, but a particularly important challenge for Asian Americans as well as other diasporic communities in the Metro Detroit area is the challenge of sourcing culturally relevant food.

Bernardo talked of the geographical challenges he faced recently when making kare-kare, a traditional peanut oxtail stew from the Philippines with eggplants, long beans and bok choi. After going to several different retailers, grocery stores and the farmers market, he was unable to find all the ingredients that he needed to make this one dish. He finally had to drive outside of the city in order to go to an Asian supermarket before he could make a dish that was so central to his family’s culture.

“We need these foods to maintain our sense of self and to preserve our sense of culture and tradition,” said Bernardo. “Because they feed us in ways that ordinary food can’t. There’s an aspect around being nourished by one’s own cultural traditions and foodways.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School students installing a bean trellis for the King Learning Garden – Photo by Neha Shah

Bernardo came to understand the importance of being able to access culturally relevant foods and how those foods can connect across lines of ethnicity while working and growing up in his family’s grocery store on the west side of Detroit.

“We sold a lot of culturally relevant food that generally was not available in grocery stores around us,” said Bernardo. “We catered to the Philippine diasporic community that worked at Grace Hospital over on Six Mile as doctors and nurses. In the over 13 years we stayed open, I came to find out a lot of staples we held closely as cultural traditions and foodways were also shared by other people in that particular part of Northwest Detroit. So I started seeing connections with the African-Caribbean community and West African community also in that area.”

Once communities begin to make connections with other communities, food justice issues begin connecting with other issues as well.

“Once you start looking at food as a justice issue, then you start to see the interconnections between food and other systemic issues regulating immigration policy, regarding the overpolicing of communities of color, meaning environmental justice issues like pollution and water shut offs, [and] access to health care. There are so many ways that food intersects with other issues. Climate change is another huge one.”

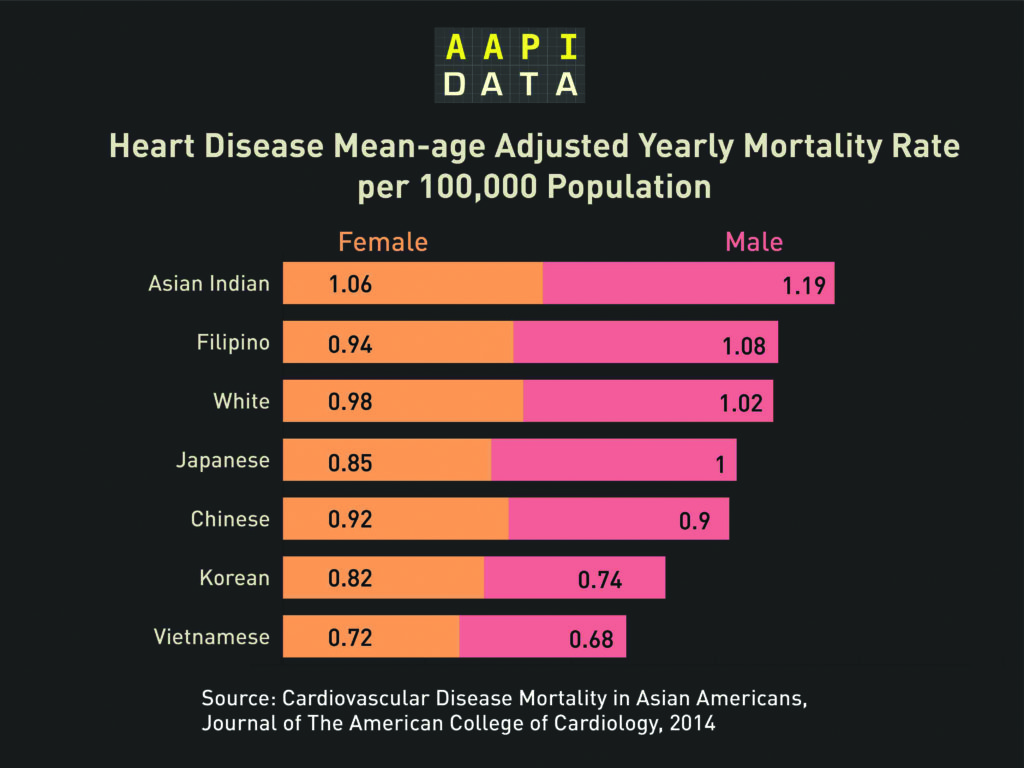

Another food justice issue particularly important for Asian Americans is the prevalence of chronic health diseases like diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease, especially among Filipino and Indian American communities. These health problems are often exacerbated by processed foods full of salt, sugar and fat, such as canned meats introduced into the cuisine by military forces. Lack of access to healthy culturally relevant foods drives both a reliance on purchasing food from gas stations and party stores as well as younger generations moving away from cultural and traditional foods.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School students painting a mural for the King Learning Garden – Photo by Neha Shah

Another food justice issue important to Asian Americans is the appropriation of Asian American food by trendy restaurateurs, which contributes to the gentrification of Detroit, driving up the costs to live in that community and eat that food.

Other Asian Americans in the food justice movement are innovating in creative ways to combine local food sourcing and sustainable growing practices with foods from or inspired by their Asian heritage such as Dorothy Hernandez of Sarap Detroit, Meiko Krishok of Guerilla Food Detroit, the Bengali American women of Bandhu Gardens and Andy Chae of Fisheye Farm.

Shane Bernardo – Photo by Melissa Jones, FoodTalksDC

There are a number of ways in which Asian Americans are a part of the food justice movement and bring their experiences to the table. At the individual level, people celebrate their culture by eating cultural and traditional foods. Many people grow their own food in backyard and urban gardens both to make ends meet and to access culturally relevant foods.

“I used to live in Hamtramck and I would often be awestruck by how many Bengali and South Asian homes would have these trellises for bitter melon and other vegetables that were synonymous with their cultures,” said Bernardo. “I also used to volunteer for Detroit Asian Youth (DAY) Project and a lot of our youth member homes would have fairly sizeable gardens. I remember one student had daikons and ducks.”

Within this context of food justice and food sovereignty, a garden is more than a garden.

“This season I will be growing a South Asian-specific garden to reclaim my heritage and culture identity,” said Anita Singh, the Youth Programs Coordinator at the nonprofit Keep Growing Detroit.

For those who want to get more involved in the food justice movement, Singh also recommends, “Listening to the community first to see what’s happening and then after some time, seeing how to contribute to that landscape.”

Community gardens are also a way to bring younger generations into the food justice movement.

At the Ann Arbor Public Schools, Neha Shah has planted a school learning garden with students for several years. She has many Asian American students and she uses the garden as a way to engage students experientially and across disciplines to learn about healthy eating, food justice, ecology, art, protecting the environment, problem solving, teamwork and more. The garden also provides produce that is shared with the school community.

“After lessons taught in my classroom and in our school garden, you see that students care about our environment more than they realize,” said Shah. “They feel connected to the earth and responsible for the environment around them. They start to realize that knowing where their food comes from is powerful. All students deserve equal access to healthy foods regardless of their class, social status and race. Those connections are vital to understanding food.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School students preparing seedlings for the King Learning Garden – Photo by Neha Shah

The garden also gives students opportunities to access the rich agricultural heritage and histories of cultures around the world, including their own heritage and history.

“There are many cultural traditions and rich history that Asian Americans give to the world,” said Shah. “There is an agricultural history that needs to be told. Traditional food and farming knowledge can be accessed and passed down from generation to generation keeping the traditions and stories alive. Sharing that with people is important. Food sovereignty and land loss exist everywhere and affect people of all colors.”

The sustainable garden is a microcosm of what is possible as more people bring their different backgrounds and approaches to the food justice movement.

“The industrialization of our food system is harming our bodies, our land and environment, and our communities. Everyone has the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods. People need to have a say in where their food comes from, how it is produced, and how the systems in place are practiced,” said Shah. “The diversity of people planting the seeds and harvesting the foods to keep alive cultural traditions and nourish communities around the country is growing. Preserving that is what will provide a true change in our current food system.”

Shah encourages Asian Americans to get involved, “There are hundreds of community-oriented projects across the greater Detroit area. You can volunteer on farms, community gardens and school gardens. There are wonderful organizations like Food Corps, Edible Schoolyard, Slow Food USA or our local chapter Slow Food Huron Valley, USDA, Michigan Farm to School and so much more. There are wonderful classes at any level of higher education institutions. There are conferences and workshops. There are the local food summit and community forums and coalitions. U of M has a food literacy for all course available for free for the public currently this semester. There are many options. Just get involved! Don’t talk about it. Do it!”

About this series

New Michigan Media (NMM) is the collaboration of the five leading minority media outlets in the region. The New Michigan Media Newspapers have a combined estimated reach of over 140,000 weekly, and include The Latino Press, The Michigan Chronicle, The Jewish News, The Michigan Korean Weekly and The Arab American News. For the past three years, NMM has also been a member of the Detroit Journalism Cooperative (DJC), the unique collaboration between some of the leading media outlets of the region, which includes The Center for Michigan’s Bridge Magazine, Detroit Public Television, Michigan Public Radio, and WDET. Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the DJC aims to report about and create community engagement opportunities in Detroit and the region. The article you are reading is part of the DJC project of this year and will appear in all the NMM member newspapers, as well as with the DJC partners.

Leave a Reply