By Mohamed Mohamed

“It was like a dream.”

That is how my maternal grandfather, Abu Ahmad, described his memories of our village near Safad in the Galilee in the northern part of Palestine, after I had curiously asked him about it as a kid. He told me it was cradled within a lush, beautiful landscape, where cherry and apple trees grew in abundance. The cucumber, tomato, and other plants did not need irrigation, because the ground water and rain in the area provided more than enough for them to grow on their own.

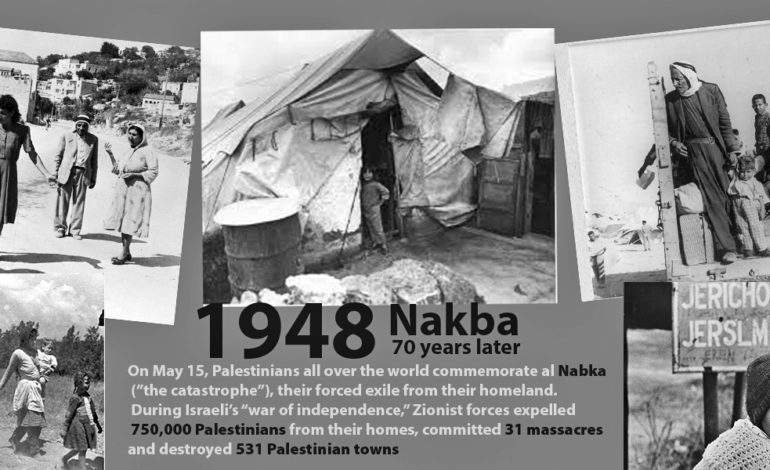

In 1948, when my grandfather and more than 750,000 other Palestinians and their families were expelled or fled from their homeland during the Nakba (or “catastrophe”) at the hands of invading Zionist forces, he was only 11-years-old. I suspect that his description of our ancestral village as a “dream” was a mixture of nostalgia along with the blurring of his memory.

On the other hand, my paternal grandfather, Abu Kasem, had a much darker story to tell. He was 24-years-old in 1948, and his recollections were much clearer and more aware of the tragedies that he and his family had to live through.

He used to constantly remind me of the names of his father, his grandfather, great-grandfather and the rest of the at least eight generations of fathers before him that he could recall. He was not speaking in a pleasant and sentimental way, but rather in a way to remind me that despite our family’s solid roots there for hundreds of years, he, his brothers and his father were the ones to carry the burden of being forced to abandon everything, while still carrying the keys to their homes in vain.

He always told me the same story of the moment that he and his family realized they needed to leave. My grandmother was busy making kibbeh, a Levantine dish made of bulgur (cracked wheat) and minced lamb, when my grandfather anxiously barged in and told her they had to leave immediately.

He heard about massacres of unarmed Palestinian civilians in neighboring villages such as Ain al-Zaitoun by Zionist Haganah terrorist forces, and he was fearful for his life and the lives of his family members. This feeling of terror was worsened by the fact that one of my grandfather’s cousins was executed in a nearby village by the invading Zionist forces. To this day, his body has never been recovered and we do not know where his final resting place was. A neighbor of my grandfather’s sister also disappeared and was never found.

Needless to say, the ground meat for the kibbeh was abandoned and left to rot in the kitchen; and my grandfather always grimly joked about how he was in the mood for this dish on that day and how he was not even able to enjoy that last meal in his home.

My grandparents quickly took my aunt Khadijah, who was an infant and their only child born in Palestine, collected whatever belongings they could carry and gathered their flock of sheep (which, along with farming, were the primary source of their sustenance). They fled north toward Lebanon and ended up travelling by foot more than 40 miles to the city of Saida. My grandfather, as well as the rest of our family, still had hope that they would be able to return soon.

Unfortunately, this aspiration quickly turned into a fantasy. After the defeat of the Arab armies in 1948, it became clear that my family, along with hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, would not be able to return to their homes. Furthermore, some of the people who did attempt to go back were killed by the Zionist occupiers. My great-grandfather was a little bit more fortunate. He did try to go back, but upon his return he faced numerous attempts of intimidation and threats to his life, so he eventually had no option but to flee back to Lebanon.

As my family’s devastating new reality became clearer, so did the imminent poverty they would face. Eventually, my grandfather was forced to sell his entire flock of sheep in order to have some amount of money available to keep them alive. In the southern city of Saida in Lebanon, they lived in tents for almost four years, which is why these communities are called refugee camps. They found a small source of relief when the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) built them (and many other Palestinian refugees) a small, one-bedroom zinc-covered barracks home. At this point, it became obvious that they had lost everything and were unlikely to get it back.

Sadly, this was not the last of the suffering my family endured as a result of Israeli aggression. During the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, in its campaign against Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) militants, Israel inflicted massive collateral damage against civilians. Many of my male family members, including uncles and second cousins, were taken prisoner by the Israeli occupying army. Most of them were tortured physically and mentally. To this day, my second cousin, who now lives in Tripoli in the northern part of Lebanon, refuses to go to Saida in the south, due to the trauma that he experienced while held captive by the Israelis. He has a constant paranoia that if he goes to the south, he will be captured and tortured once again.

My grandfather was not captured by the Israelis, but what he suffered is arguably worse. In its invasion of Lebanon, Israel formed an alliance with the right-wing Lebanese militias fighting Palestinians and provided them with weapons, training and other assistance. During the invasion, my grandfather’s home was torched by these militias, which, as in the case of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, were given the green light to do so by the Israelis. Yet again, he lost his home and his entire possessions.

More than a decade later in the early 1990s, my grandfather had a rare opportunity to visit our village through a program run by the U.N. He was able to go back for a heartbreakingly short four-week stay and connect with some of the few family members who managed to stay in Palestine. I cannot begin to imagine the immense pain that he must have felt as he departed back to Lebanon, probably knowing that he would die and never see his homeland again. Sure enough, he passed away only a few years later.

My grandfathers and their families were the ones who had to live through the dispossession, despair and devastation that the Nakba inflicted upon their lives, but, unfortunately, it did not end with them. Through his education and hard work, my father was able to make it out of Lebanon and avoid much of the violence of the Lebanese civil war and Israeli invasion, and he ended up immigrating to the United States. That is why I am here today and, admittedly, I am fortunate that I did not have to experience as many of the consequences of being a Palestinian refugee.

With my great privilege as an American citizen, I decided to try to visit my ancestral homeland a decade ago, thinking that I would be successful. However, I quickly realized that Israel has no respect even for the citizens of its greatest ally and protector, the United States. After hours of extensive questioning by several Israeli officials upon my entry, one of these interrogators had the nerve to ask me what I was doing there. At that point, I was infuriated, and since she had previously mentioned to me that she is originally of Polish origin, I asked her what SHE was doing there. Even though my family had lived in our village in Palestine for more than eight generations, she somehow felt that she had more of a right to be there than I did. This, of course, did not matter to her and, eventually, I was denied entry into my homeland.

Despite this encounter, my experience is unique and privileged. To this day, generations later, most of my aunts, uncles, cousins and other relatives continue to live in the squalid refugee camps of Lebanon and Syria. They face a bleak life with little to no economic opportunity. In Lebanon, my relatives lack some of the most basic rights that we take for granted. In Syria, they are living amid a devastating civil war and many of them have tragically been displaced and are going through another refugee experience. For them, even 70 years later, they are not much better off than how my grandparents were during the Nakba and they only wish they could be in their homeland.

This is my family’s story; but, sadly, most Palestinians who were forced into exile in 1948 have gone through similar, if not worse, experiences. Fortunately, Palestinians have remained steadfast in the face of Israeli oppression and injustice. Seventy years of displacement and repression have been unable to break their will and resilience.

That is why, as Israelis continue to murder people in Gaza who are protesting for their right to return to their homeland, it is more important than ever for Palestinians and their supporters to reaffirm this right. Israel might think that eventually, the newer generations of Palestinians will forget and abandon their struggle, but that would be a huge mistake. Whether in Gaza, the West Bank, in historic Palestine, in the refugee camps of neighboring countries or in the diaspora throughout the world, Palestinians will never forget.

Mohamed Mohamed is the executive director of The Jerusalem Fund and Palestine Center. The views in this brief are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Jerusalem Fund.

Leave a Reply