DEARBORN – Between 1995 and 2012, thousands flocked to the capital of Arab America for a taste of their homeland’s culture, where nostalgia for music and food alike would meet their match at the Arab International Festival.

It was a kind of celebration one could only experience in a city in which nearly half its residents are of Arab decent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and the Washington, D.C.-based Arab American Institute.

It has been called the largest gathering of Arab Americans.

The three-day festival drew in about three times Dearborn’s population of nearly 90,000, as Arab World superstars and Mediterranean food vendors featured a newly settled community rich and proud in its culture and ambition.

However, the dramatically different socio-political climate post-September 11 and President Trump’s election have marred efforts by the highly concentrated Arab American community to celebrate as loudly and publicly.

Groups with anti-Arab and anti-Muslim declarations began to visit too frequently and protests turned the festival into a costly liability.

“We need to think about how we would ensure that we have full control over the event and how we can prevent groups from turning it into a circus for their platform” – Hassan Jaber, ACCESS co-founder

But while hate groups continue to threaten the festival’s viability in Dearborn, Arab Americans in Texas, Oregon, New York, and elsewhere are hosting festivals attracting nearly 10,000 visitors and aimed at showcasing all types of entertainment and local food vendors, “while allowing the community to learn more about the Arab culture and to address misconceptions and stereotypes that are still prevalent in today’s society”, as Massoud Khayyat, who does marketing for the Arab American Cultural Society, put it.

As Dearborn’s Arab festival once offered some of the culture’s best to the region, many community members have raised questions about bringing back the Arab cheer while the community basks in post-election successes amid politically tumultuous times.

Fay Beydoun, director of the American Arab Chamber of Commerce, which ultimately became the festival’s organizer and decided to shut it down, told The AANews that the chamber is currently in talks with major stakeholders about a renewed Arab festival in Dearborn.

Stakeholders include local organizations and sponsors to host a festival that employed the best practices it could to help prevent “radical protestors.”

“We understand the importance of the festival and what it means to the community,” Beydoun said. “But we also have a responsibility to protect attendees and provide a safe environment.”

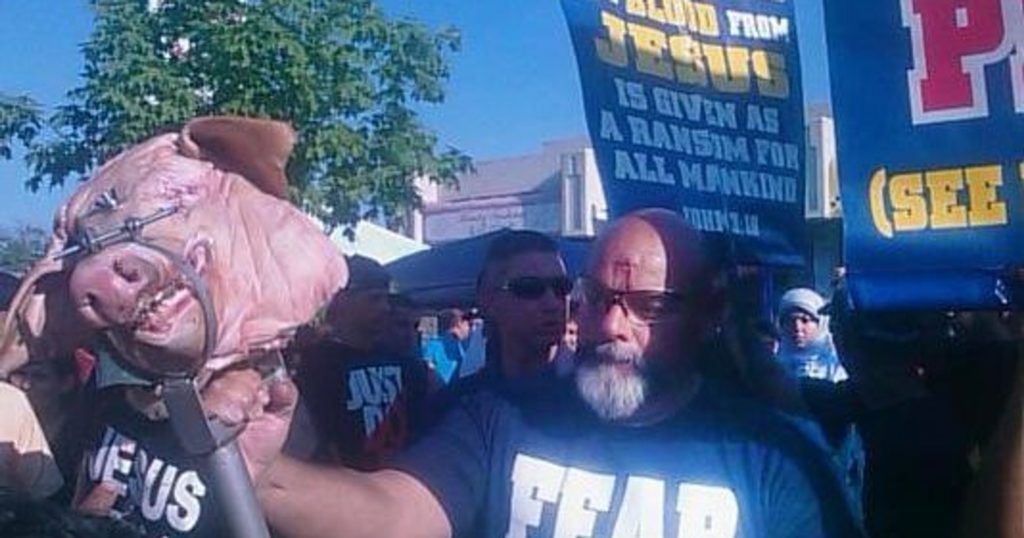

Evangelical protesters at 2012 Arab International Festival in Dearborn – Photo by the Detroit Free Press

Beydoun alluded to a controversial incident during the 2010 festival where Christian missionaries were arrested for heckling attendees while recording their reactions. They were charged with disturbing the peace, but were later acquitted.

In 2012, another Christian group brought a pig’s head mounted on a stick and carried explicit anti-Muslim messaging, resulting in violent verbal and physical exchanges.

Beydoun added that the festival was caught in between too many lawsuits and an increasingly high insurance cost of about $55,000.

“[The festival] could no longer financially sustain itself,” she said.

But the festival was initially not only a celebration of culture, but also a means for the city to attract shoppers to Warren Avenue, where most Arab immigrants opened their shops, according to Ali Jawad, founder of Leaders Advancing and Helping Communities (formerly the Lebanese American Heritage Club).

That’s why, with the help of the Warren Avenue Corridor Authority Commission, Dearborn promoted the festival as a means to promote restaurants and other businesses along the avenue, he said.

The event also brought in more than 200,000 visitors from across the country, many of whom stayed at hotels in the city.

Video grab from the 2012 Arab Festival in Dearborn

The LAHC partnered with ACCESS on organizing the festival’s major debut in 1995. It was a major hit, as attendees were peeking through fences to get a glimpse of Lebanese singer Walid Toufic, the night’s featured entertainment.

“The idea was to promote our culture in the right way,” Jawad said. “But after Sept. 11 and the incidents, it started to lose value. The merchants didn’t want it anymore.”

Besides, he added, many Islamic institutions have since opened on Warren Ave., suggesting Belle Isle or other places in Detroit as better venues for a future festival.

Today, Dearborn is working on a redevelopment plan for the Warren Ave. corridor.

That’s why Mayor Jack O’Reilly has been “very eager” for a comeback of the festival, said Hassan Jaber, co-founder of ACCESS, the largest Arab American community non-profit.

Jaber said the mayor has had conversations with department heads about playing a role in putting on a successful event and that there is a focus on ensuring the same safety “mistakes” wouldn’t happen again.

“We need to think about how we would ensure that we have full control over the event and how we can prevent groups from turning it into a circus for their platform,” he said.

Jaber added that from the beginning, the mostly Arab business owners saw the festival as an asset, which is why ACCESS teamed up with various local organizations, including the LAHC and the Arab American Chamber of Commerce, to “celebrate community, heritage and culture.”

It was an opportunity for community members to “take pride in who they are and identify the festival as the ‘go-to’ event of the year.”

With the partnerships came exponential success, making the festival a popular national event and Warren Ave. a thriving business hub.

A girl climbs a ladder at the 2010 Arab International Festival in Dearborn

But then, the community organizations’ priorities shifted after the Sept. 11 attacks.

“There was this relentless campaign against the community, the festival and our institutions,” Jaber said. “The festival became a target for hate groups.”

Jaber said ACCESS ultimately took a step back to focus on strengthening social service and civil rights campaign efforts. The Arab American Chamber of Commerce became the main organizer of the festival, before deciding not to host the event again in 2013.

Ismael Ahmed, co-founder of ACCESS and senior advisor to the chancellor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, told The AANews he doubts whether its “worth it” to host a festival drawing in about 300,000 people on Warren Ave., considering the difficult logistics.

Ahmed said the festival’s history dates back to the mid-60s, when the Arab immigrant community was just settling in Dearborn’s Southend. It was born out of discussions between ACCESS and the Southeast Dearborn Community Council. Ahmed credits the SDCC for “saving Southeast Dearborn”, after suing the city for wanting to demolish homes to build an industrial park.

It was during a time when Dearborn’s make up included many Italians, Eastern Europeans and Latinos, and the festival drew in more than 20,000 people over the weekend.

As the festival grew, it became community collaboration that included the Islamic Center of America, attracting about 30,000 people at its peak.

At one point, southern Christian groups were driving hundreds of volunteers to assist with the festival. But once other Christian groups began to repeatedly attack the festival, the city “became uncomfortable with the consequences” of being tied up in court.

At the same time, Ahmed said many community institutions like ACCESS and the LAHC began prioritizing offering scholarships and social services and fending off attacks by the Trump administration and the heated political climate.

“Both organizations became very active in the work they do and just didn’t have the energy [for the festival],” Ahmed said.

Photos courtesy of the Arab American National Museum

For a few years, the Arab American Chamber recruited merchants, brought in many vendors and hosted the festival, while ACCESS instead put on its Concert of Colors festival. That festival brings in about 30,000 over a weekend and is hosted in partnership with the Detroit Institute of Arts, The Michigan Science Center, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Detroit Historical Museum, among other venues.

ACCESS also organizes an Arab American tent, which features music and food, during the Dearborn Homecoming event.

A group of Arab and Chaldean activists also organizes an annual Arab and Chaldean Festival in downtown Detroit’s Hart Plaza.

However, all past organizers interviewed said they didn’t recognize those events as substitutes for an Arab festival.

The question is, how long will it take for the most highly concentrated community of Arab Americans to celebrate their heritage and milestones as proudly as they did before outside forces began to define them?

Leave a Reply