A CIA document recommended that the “U.S. should consider sharply escalating the pressures against Assad” through the orchestration of “simultaneous military threats against Syria.” Three years later, that same conviction appeared in a memorandum that “explores alternative scenarios that could lead to the ouster of President…al-Assad in Syria.”

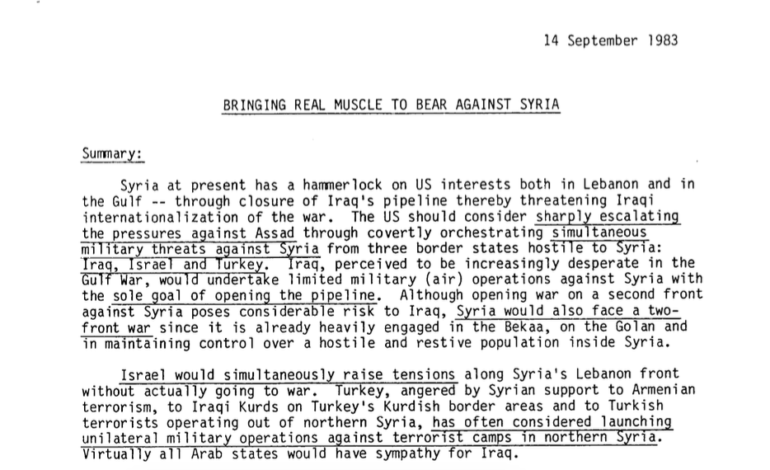

These aren’t excerpts from Hillary Clinton’s email server nor are they CIA documents from 2011. Rather, these are excerpts from memorandums from 1983 and 1986 detailing the United States’ political prospects in Syria, entitled “Syria: Scenarios of Dramatic Political Change” and “Bringing Real Muscle to Bear Against Syria.”

Forced regime change had been a template of U.S. policy in post Cold War Middle East. While the most notorious of these incidents involved the deposition of democratically elected, progressive Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mosadegh in 1953 in a CIA coup, Syria set the template for Middle East regime change four years earlier when President Shrukli al-Quwalti was overthrown in a CIA-supported coup.

The U.S. had aspirations for a U.S.-sponsored pipeline that ran from Saudi Arabia to the Mediterranean, and Syria had been an obstacle throughout its construction, especially under al-Quwalti, who opposed the pipeline.

The 1983 document also showed that the foreign commitment towards the pipeline had not waned, nor had its dedication to instigating proxy conflicts for its sake. Even then, the “opening of the pipeline” was expected to “be a sharp blow to Syria’s winning streak” and its “prestige and authority would sustain significant damage.”

The document also outlined the U.S.’ desire to counterbalance Syrian influence via Iraq, Israel and Turkey. In rousing three bordering states against Syria, the “orchestra[tion] of a credible military threat against Syria” would possibly, “induce at least some moderate change in its policies.”

Iraq was encouraged to poise itself to war against Syria to divide its attention during its then-involvement in Lebanon. Israel was recommended to “welcome the chance to humble Assad”, while Turkey’s existing contention with Syria was seen as an opportunity to sustain geopolitical containment without much work or interference on that front.

Yet the four decades of opposition to the Assad dynasty had failed to result in any regime change. Additionally, the U.S. approach to Syria engendered a considerable amount of nuance during this stretch of time.

“U.S. policy shifted from hostility-but not regime change-in the 1980s to cooperation in the 1990s,” said Daniel Neep, assistant professor in the Politics of the Arab World at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.

At the time, the Reagan administration remained engaged with the Syrian regime, maintaining a relationship that reflected a tense Cold-War approach where bitter contention against the Soviet Ally was met with tense trepidation in an approach that sought to contain the fragile balance of power.

As foreign policy realists, U.S. officials were exemplary in maintaining their regional interests over focusing on making friends. The 1990s rang in a comparatively more cooperative period with Syria, marked in part by then-Secretary of State James Baker’s frequent meetings with Assad as priorities shifted from containing Russia to curtailing Iraq in the advent of the Gulf War.

Neep added that between 2001 and 2003, Syria and the U.S. “saw cooperation in the War on Terror” before “a dramatic worsening of relations after the U.S. invaded Iraq.” Syria, despite maintaining its 1979 designation as a state sponsor of terrorism, was a partner in military intelligence sharing after the September 11 attacks.

Of the most treacherous instances of the U.S.’s complicit collaboration with Syrian military intelligence was evident through the case study of Maher Arar, a telecommunications expert and Canadian national who had fled Syria 15 years prior to his unfortunate 2002 detainment.

It was during this time that the curious feature of U.S.-Syrian collaboration in torture was evidenced by Arar’s detainment without charge in a Syrian prison, where he was tortured for 10 months in a three by six foot cell.

Arar also claimed that the interrogations in Syria mirrored those he received upon detainment at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York.

Nonetheless, numerous U.S. officials continued to seek military involvement against Syria, such as John Bolton, the undersecretary of state (and later U.S. ambassador to the United Nations) during the administration of George W. Bush, who accusing Syria— as well as Cuba and Libya— of seeking to acquire or being in the possession of weapons of mass destruction.

State Department intelligence official met Bolton’s alarmist claims with disagreement, dismissing his accusations as exaggerated.

Nonetheless, U.S. relations with Syria soured following the post 9/11 period of relative detente after yet another pretext of international coalition building waned as it had after the Gulf War. Bush cited ties to terrorism as a reason for slapping sanctions on Syria in 2004, returning to business as usual in re-instating a decades-long hawkish stance against the regime.

A more aggressive pursuit of regime change followed Bush’s complete cessation of diplomatic ties with Syria in 2005, with the U.S. continuing to fund opposition groups though to the 2011 Arab Spring protests. Months before the 2007 elections, “election monitoring”, public opinion polling and secret funding of opposition parties were to be spearheaded through the National Salvation Front, according to a proposal from late 2006.

Lord Palmerston, a 19th century British prime minister, described nations having permanent interests rather than permanent friends. The U.S., in its approach to Syria, embodies this cynical realism of over seven decades of intervention, where a bitter ongoing extension of cold war hostility was punctuated only by brief bouts of counterterrorist collusion before resuming to another chapter of austerity.

Rinse and repeat.

Leave a Reply