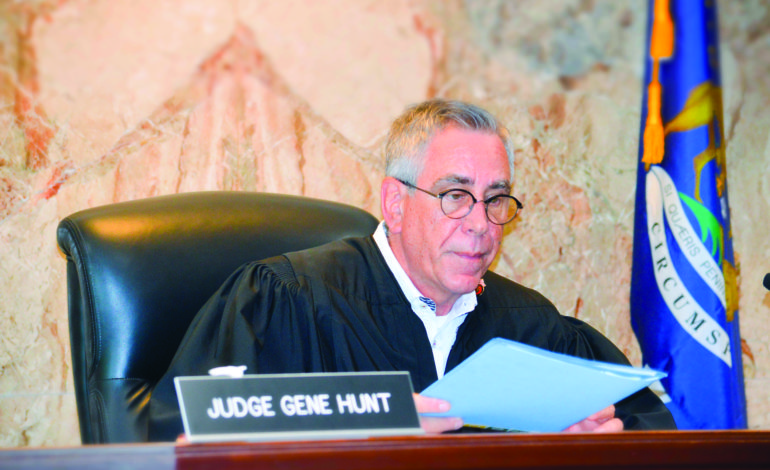

DEARBORN — In the chambers of newly minted 19th District Court Judge Gene Hunt, music from counter-culture America echoed off walls adorned with signed portraits of The Beatles, of his children and Fordson High School football teams he used to coach.

It had only been 112 days since Hunt was invested as a judge, yet he appeared confidently at home.

Hunt, 62, is no stranger to the Dearborn court and others in the area, having been a defense attorney for more than three decades before fighting for the seat in a fierce 10-month campaign that won him 50.4 percent of votes last November.

On May 17, the high-spirited, introspective judge reflected on the cases that appeared before him that day. He was in the middle of a two-week rotating shift to hear all misdemeanor cases, while judges Sam Salamey and Mark Somers tried civil and criminal cases.

That day’s docket included cases involving individuals charged with driving with a suspended license; possession of marijuana; larceny and teenagers caught up in a fist fight.

Although each defendant who sat in the courtroom’s well (the audience’s seating area) appeared undoubtedly anxious, Hunt’s unostentatious command of the courtroom dissolved most of the tension.

Although each defendant who sat in the courtroom’s well (the audience’s seating area) appeared undoubtedly anxious, Hunt’s unostentatious command of the courtroom dissolved most of the tension.

Hunt’s handling of ruffled defendants appearing before the bench demonstrated they are not merely case numbers to him, but individuals with a story and accrued circumstances that led to their presence in court.

While hearing the scheduled afternoon cases, Hunt carefully considered prosecutors’ recommendations; referred to charges as “allegations”; ensured rights and fines were understood and lent a sympathetic ear when warranted.

In finding common ground between the court and some individuals at the podium regarding the payment of penalties, for example, Hunt divulged his judgement – not as a means for punishment, but a commitment to helping people “get back on their feet.”

Almost all were African Americans, except for one White and one Arab American man. In fact, Hunt said most misdemeanor cases he administers involve Blacks.

In making his rulings, he considers the gravity his decision weighs on the individuals and families before him. He also bears the ultimate responsibility of being able to use his discretion in imposing judgments that affect the lives of others.

The eighth person to appear before him that afternoon was a White man arrested earlier that day following a traffic stop, because he had accumulated outstanding fees and failed to report to probation. He received probation after having driven with a suspended license and having been in possession of marijuana about five years ago.

The man, having just been in jail, told Hunt he’d greatly struggled in finding a job and reliable transportation to pay off the fines. And it seemed every time he would get behind the wheel, he would find himself in a jail cell. He said this cycle preventing him from rectifying his drawn-out predicament.

The man also revealed that he’d previously served a 10-year prison term for the attempted murder of the man who’d tried to rape his sister.

However, he also said he’d recently been offered a job at a relative’s new landscaping business. Hunt took the occasion to give the man another chance – a deserved opportunity for everyone, he later told The AANews in his chambers – and worked out a plan to eventually eliminate the fines.

Earlier that day, Hunt heard the case of a commuter who couldn’t pay a traffic ticket he’d received years ago, and who’d accumulated $10,000 in driver responsibility fees.

According to Hunt, about 80 percent of cases he’s tried that involve driving with a suspended license result from individuals who could not pay a traffic ticket or even afford insurance. Some even struggled to pay rent.

To his initial surprise, a growing number of fines were being paid in February. Hunt soon realized it was because people were receiving their tax refunds and had the resources to pay.

Payment of fines is the second common reason why people end up in Hunt’s courtroom. By contrast, the gravest problem facing the community is opiate addiction –abusing prescription drugs that subsequently results in habitual misbehavior.

Later in the afternoon, a third wave of defendants awaiting a verdict took their seats. They consisted of Arab American high school students and their parents. Some of the teens were charged with theft from a local shopping center; some had gotten into a fist fight and others had crashed their parents’ cars.

Hunt took time to review their files and ensured the kids’ story corroborated the reports. In each case, Hunt asked what their grades were like and requested they submit their final GPA results to him at the end of the school year.

Back in his chambers, Hunt stressed the importance of education and securing an incentive for troubled students to try harder in school and using the opportunity to exercise discipline. He said that’s better than requiring them to go through several days in a work program, although he did order a few of the teens to participate.

Back in his chambers, Hunt stressed the importance of education and securing an incentive for troubled students to try harder in school and using the opportunity to exercise discipline. He said that’s better than requiring them to go through several days in a work program, although he did order a few of the teens to participate.

Hunt said that during his years as a lawyer and public defender, his job had always been to advocate for and find ways to help his clients in the way they would have done themselves, if they were as familiar with the law.

His current job is comparable; the difference is his duty as a judge to enforce the law.

In making his rulings, he considers the gravity his decision weighs on the individuals and families before him. He also bears the ultimate responsibility of being able to use his discretion in imposing judgement that affect the lives of others.

That is why it’s vital that judges and police officers, who also use discretion, transcend internal biases, he said.

With conviction, Hunt added that although he thought he would struggle in making fateful decisions, it actually is “all clear” to him. He abides by two basic standards: That a decision helps an individual and that the law is respected in doing so.

“Every person comes in front of me on the same set of feet,” Hunt said. “But it’s more important to get them help, not punish them.”

In the courtroom, Hunt faces the challenge of upholding mandates and legislation set by a government that enacts blanket laws, and a sense of moral obligation to be in the service of those are tried before him in his hometown.

Hunt, a pragmatic idealist, strived that day to be a champion of the people in his community — which is where he said the justice system’s commitment should be — in an age where the powerful often readily persecute the weak and underprivileged.

“I will remember that there is no case too small or too trivial,” Hunt proclaimed after he took the oath of office during his investiture in January. “I will keep in mind that to the people before me, these cases are not small and trivial to them.”

It seems Hunt has kept that promise throughout his first 100+ days in office.

Leave a Reply