DEARBORN— Can you imagine a borderless planet? Where people are free to roam from one region to another? Where knowledge is easy to access and everyone’s desire to travel can be satiated without barriers or lines at airport security?

Or can you imagine your daily routine of family time, work, dinner and prep for the next day of work being interrupted by war and military personnel filling the scene outside of your window?

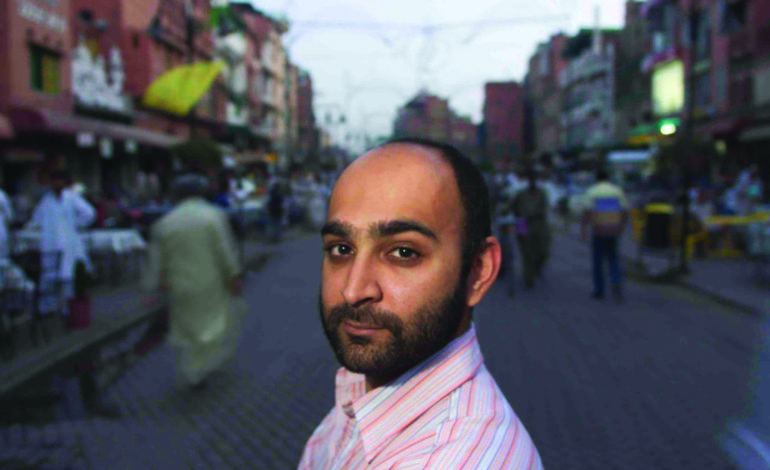

Novelist Mohsin Hamid has written about migrants and empathy in his latest book, “Exit West”, which follows a couple in their love story and their travels as refugees.

Hamid visited UM-Dearborn to discuss “Exit West” and have a candid conversation.

He was born in Pakistan in 1971 and moved to California with his parents, so his father could complete a PhD program at the University of California.

“I was clearly quite shaken by this experience; I was a talkative kid,” Hamid said. “Words were pretty central to what I was.”

Hamid didn’t speak English when he arrived in the States and he said that after one incident where his English-speaking neighbors couldn’t understand him, he quit talking. For 30 days, he seldom spoke. Instead, he watched a lot of television.

“A month later I began to speak and my parents were surprised to find I spoke English in an American accent,” he said. “I had absorbed TV for one month, and that is all I needed.”

At the age of 9, Hamid and his parents moved back to Pakistan, where his parents realized Hamid had forgotten how to speak Urdu.

“Urdu became my third language,” Hamid joked, referring to the ironic fact that he’d forgotten his native language during his time in the States and had to relearn it.

He added that though he did well in school, he always felt his English skills were better than his Urdu.

Once Hamid was 18, he moved back to America, where he attended Princeton University and then went on to graduate studies at Harvard Law School.

While studying in the U.S., a college roommate pointed out that he spoke differently to his mother than he did to the roommate.

Hamid recognized that he had been trying to blend in to wherever he was living.

“I thought when I was younger that I was basically a foreigner everywhere,” he said.

Through Hamid’s experiences of living back and forth between Pakistan and America, and also London, it wasn’t that he was foreign, but that everyone around him was foreign, too.

Hamid said that a daughter with all brothers or a gay person in an all straight family may feel foreign.

“The notion of being somewhat foreign is somewhat universal,” he said. “There is something we can all connect on.”

He said “Exit West” talks about the concept of the migrant apocalypse and refugees. He also said some people reference refugees by saying they haven’t paid their dues and that they want free stuff. But Hamid said he feels such people have a misunderstanding of refugees’ predicaments.

Hamid said a refugee may have left their parents, best friends, acquaintances, familiar food and music, as well as architecture and even familiar smells.

“What more can you ask of people who have given up everything except their lives if that’s all they have?” he asked.

Hamid said he moved to London in August 2001. After the 9/11 attacks the following month, he felt the New York and America he’d known was gone.

Post-9/11, when he would enter the U.S., Hamid would encounter secondary security screenings, which would inconvenience his travels.

“I started to realize that it was a process,” he said. “I was never denied access to the U.S.”

One time, he was pulled off of his plane in North Carolina. The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agents apologized to him and said a new employee was working when he went through who was unaware that he needed to be screened. The agents conducted an extremely fast screening so Hamid wouldn’t miss his flight.

In 2014, Hamid wrote an article published in The Guardian about why he believes global migration is a fundamental human right.

In one section, he said he believes that in the future the scale of migration will be unlike what has been seen in the past, and issues such as climate change, disease, state failures and wars will push people to move.

“If we do not recognize their right to move, we will be attempting to build an apartheid planet where our passports will be our castes, and where obedience will be enforceable only through ever-increasing uses of force,” he said.

When an attendee at the UM-D event asked why Hamid wrote love stories, he brought up suicide.

He said the fundamental prediction about being human is that no person will get out alive and that there are two approaches a person can respond to this realization of mortality.

“Spoiler alert, it isn’t going to work out for anyone,” he said.

Hamid said one response is that a person might turn away from the future and sink into a political and cultural depression.

“If you think that there’s a fundamental symbolic act of our time, it is the suicide bomber or the suicide shooter in America,” he said.

He said he believes the suicidal impulse is a manifestation of society today.

A love-based approach is the second way to respond. Hamid said it’s where a person who experiences love, and cares about something outside of themselves, will find the notion of death less depressing and no longer a “be all end all of life or rather it is part of the story.” This approach is one of the reasons why he writes about different types of love.

Currently, Hamid resides in Lahore, Pakistan, in a house next door to his parents. He said every morning his children play with their grandparents before school, and this is what motivates him to live in Pakistan.

“I’m a man who is committed to a profession, to a marriage with my wife, whom I’ve been with for 14 years,” Hamid said. “But when it comes to geography, I’m a little bit of a wandering eye. I come into a nice looking city and I think Amsterdam—yes! This could be something.”

If you want to read one of Hamid’s books, visit www.mohsinhamid.com

Leave a Reply