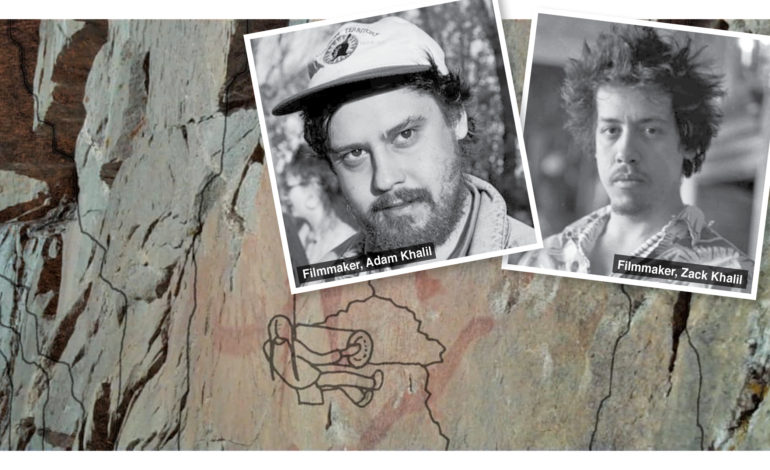

BROOKLYN, NY — “We say we’re Ojibtian.”

Adam Khalil and his younger brother Zack use that term when referring to their maternal indigenous Ojibway roots, and their paternal Egyptian heritage.

Khalil’s mother is Native American, and his father is Egyptian.

Khalil, 29, grew up in Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula with his mother and brother after his parents divorced. In his early years, he moved around with his brother and parents. By the time he was 9-years-old, he’d lived in Cairo, Boston and London.

Khalil, who now lives in Brooklyn, has always identified strongly with his Ojibway roots.

“It’s something I actually feel kind of cut-off from,” he said of his Arab ancestry, since he didn’t know of any Arab Americans living in Sault Ste. Marie, and his father had chosen not to live there.

Despite this feeling, Khalil said he still felt very strongly about his Egyptian heritage growing up.

“I had this weird ability to code switch between passing for White, passing for Ojibway and invoking my Egyptian identity as I pleased.”

After the 9/11 attacks, Khalil noticed the negative views in his community about Arabs and Muslims, so he, his mother and brother decided to host an Egyptian meal for their friends to illuminate their understanding of Arabs.

Khalil has been connected to his Egyptian heritage through his studies and beliefs in politics and art. He’s also seen parallels on both sides of his family.

He said that he saw similarities in storytelling.

“Ojibway storytelling and Egyptian storytelling are pretty similar,” he said. “It’s like slightly exaggerated.”

He’s seen other similarities, too.

“Hospitality and kinship networks are similar,” he said. “Middle Eastern hospitality is intense. Killing you with kindness, for real. And Ojibway stuff has the same vibe. If you’re hungry and you’re around someone, they’re gonna feed you.”

He also said both cultures have a sense of altruism.

Growing up, Khalil enjoyed watching films, and his travels as a child sparked an interest in the world outside his town.

After high school, he received a millennium scholarship and chose to attend Bard College in New York.

He was undecided about what he wanted to do while at Bard, so he chose to take a break and move to the west coast. He attended City College of San Francisco and ultimately learned, firsthand, about film from filmmaker Craig Baldwin.

He eventually returned to Bard College and discovered that the school was known for its film studies program. In 2015, he did the cinematography for a film called “The Native and the Refugee”, in collaboration with Matt Peterson and Malek Rasamny.

For the film, he spent time with the film team in Jordan, Lebanon and the West Bank.

He said he discovered more parallels between his Egyptian and indigenous ancestries on that project.

He also commented on the interesting concept of manifest destiny and Zionism.

“Which is almost like a spiritualist version of colonialism,” he said.

He said that he learned that some Native Americans went to Lebanon to fight with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) during Lebanon’s civil war.

While touring Palestinian refugee camps, Khalil and his team played films for those living there.

“People were like, ‘We didn’t know the red Indians were still fighting, we didn’t know they existed anymore,'” Khalil said. “It was neat to expose that history that has been suppressed internationally.”

Khalil said that a big thing for him as a Native American, and also others who identify with indigeneity, is sovereignty, and to be able to deal with other countries on a nations to nations basis, as opposed to having to go through the prism of the United States government.

“We were in the West Bank for three weeks and there was this ritualized violence,” he said. “Every day, school lets out at 3 p.m., kids start throwing rocks, 3:30 the IDF opens the big blue door and they’re shooting with rubber bullets and tear gas and then the big truck comes out. We were shooting [filming] the entire time.”

He said that seeing the necessity for political violence shook him. He said he’d asked people there why they throw rocks and the response was, “If we don’t, we don’t exist.”

Khalil has come to the conclusion that public colonialism is still very active.

He and his brother are working on a film called “Empty Metal”, which is set to come out early next year. The film raises questions surrounding political violence, a topic that Khalil said came up often during the process of “The Native and the Refugee.”

He said “Empty Metal” might appear cathartic, and that it raises questions about what it means to pick up a gun and what subsequently happens. It also examines what it means to be an ally or an accomplice.

Khalil was recently in Ypsilanti and Grand Rapids, where he screened his latest film, “Inaate/Se”, which was filmed in Sault Ste. Marie and concerns the history of the Ojibway in that community.

For more information about Khalil, visit www.inaatese.com.

Leave a Reply