The Oslo Accords 25 years later.

As Palestinians prepare to lower the flag over their shuttered mission in Washington, no one can predict when they’ll return to the city where just a quarter of a century ago a diplomatic triumph was celebrated on a sunlit White House lawn.

Hosted by then-President Clinton, Palestinian and Israeli leaders came together on Sept. 13, 1993 to sign the first of the Oslo Accords, designed to be the foundation of a permanent peace deal within five years that would create two states, side-by-side.

PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat (R) gestures to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (3rd R), as President Clinton (2nd R) stands between them, following their handshake after the signing of the Israeli-PLO peace accord, at the White House in Washington September 13, 1993. Also in picture is Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres (L). REUTERS/File photo

The three men who would win the Nobel Peace Prize the next year — Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres of Israel and Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat — did not live to see peace in their time.

Now, with relations between President Trump and the Palestinians, who see him as an unquestioning ally of right-wing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, at a breaking point, the Oslo deal seems like a relic from a bygone age.

Support for a two-state solution fell to 43 percent among Israeli Jews and Palestinians in one opinion poll, the weakest in almost two decades

As if to drive home the flaws inherent in Oslo’s original Declaration of Principles, 25 years later it’s the very issues that were postponed for later resolution that now dominate the headlines once again.

They include the status of Jerusalem — claimed by both sides as their capital — the fate of millions of Palestinian refugees from wars dating to 1948, Israeli settlements on occupied land that Palestinians want for a state, mutually acceptable security arrangements and the issue of agreed borders.

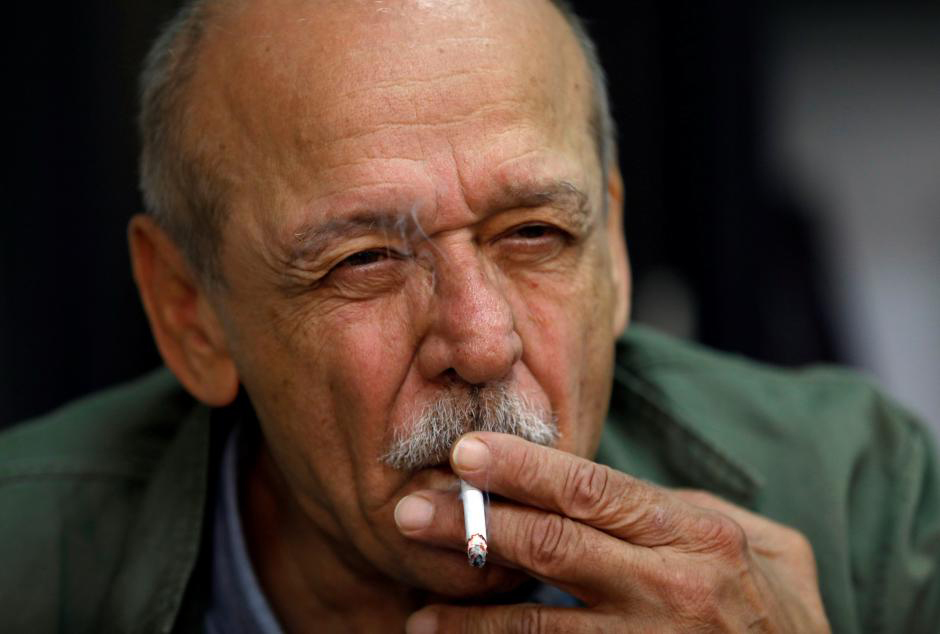

Yasser Abed Rabbo, 73, former official of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), smokes a cigarette during an interview with Reuters, in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank September 9. -REUTERS

“I believe now that Oslo is dead,” said Yasser Abed Rabbo, who was among the tiny circle of Palestinian politicians entrusted by Arafat with the secret that Israeli and Palestinian negotiators had begun meeting in Norway in 1992.

Now 73, Abed Rabbo concedes his side made mistakes. Now, few even talk of a peace process. Last month, support for a two-state solution fell to 43 percent among Israeli Jews and Palestinians in one opinion poll, the weakest in almost two decades of joint Palestinian-Israeli survey research.

“We should not mourn a ghost,” Abed Rabbo said. “We should have a new strategy — not to abandon the right of self-determination for the Palestinian people, not to abandon the right to build our own independent state, but to try to find ways and means to reach that goal different from the ways and means that we have used in the past.”

But Yossi Beilin, one of the Israeli negotiators in the Oslo talks, said the parameters of a final agreement are well-known.

“It shouldn’t take too long, once the right people are in their positions, to cut a deal,” Beilin, 70, told Reuters.

“Trump is not a game-changer — he is a spoiler … but he will not be there forever,” Beilin said. “And I believe that it is eventually, as it was in Oslo, up to the parties. If we and the Palestinians want to make peace, we will make peace.”

The early hope of peace shattered quickly after Rabin and Arafat awkwardly shook hands on the South Lawn.

Two years later, Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli ultra-nationalist opposed to peace policies that had already been tested by the massacre of 29 Palestinian worshippers by a Jewish settler in the West Bank city of Hebron, and by suicide bombings by the Hamas and Islamic Jihad militant groups that killed 77 civilians and soldiers in Israel and the occupied Gaza Strip.

Over the years, peacemaking became mired in accusations of broken promises on both sides and more attacks by Palestinian militants; and continued settlement expansion, movement restrictions, arrests and military incursions by Israel.

At the end of 2017, the United Nations said there were 611,000 Israelis living in 250 settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, both of which were captured by Israel in the 1967 Middle East war. Most countries view those settlements as illegal. Israel disputes this.

Israeli-Palestinian peace talks collapsed in 2014. Trump has pledged a “deal of the century” to end the decades-old conflict.

Trump recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital led the Palestinian leadership to boycott Washington’s peace efforts

For his part, Netanyahu has said that any future Palestinian state must be demilitarized and must recognize Israel as the state of the Jewish people — conditions that Palestinians say show he is not sincere about peacemaking.

And Palestinians fumed when Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December and moved the U.S. Embassy there from Tel Aviv in May.

Both steps have led the Palestinian leadership to boycott Washington’s peace efforts spearheaded by Jared Kushner, Trump’s senior adviser and son-in-law.

Further moves saw the Trump administration withhold hundreds of millions of dollars of aid to the U.N. refugee agency dealing with Palestinians and to hospitals in East Jerusalem; and the order to close the Palestine Liberation Organization’s mission in Washington, which opened in 1994.

In Gaza, ruled by the Islamist Hamas since 2007, two years after Israeli soldiers and settlers withdrew, one of the group’s senior leaders, Mahmoud Al-Zahar, said the Oslo deal was not a peace pact but “100 percent surrender” for the Palestinians.

Lucy Bar-On, a 60-year-old Israeli nurse, said the failure to move forward along the peace path charted by the interim agreements only emboldened hardliners.

“They won,” she said. “The extremists on the Israeli side and those on the Palestinian side.”

Leave a Reply