By Nimri Aziz

Perhaps the most agonizing experience for a family, for any bystander, even for humanitarian professionals, is a double tragedy —a death or calamity where they are refused access, where they are forced to helplessly witness suffering, unable to offer succor. This is surely what faces millions of able-bodied Syrians today. It affects Syrians within the stricken nation along with their faraway relatives and friends.

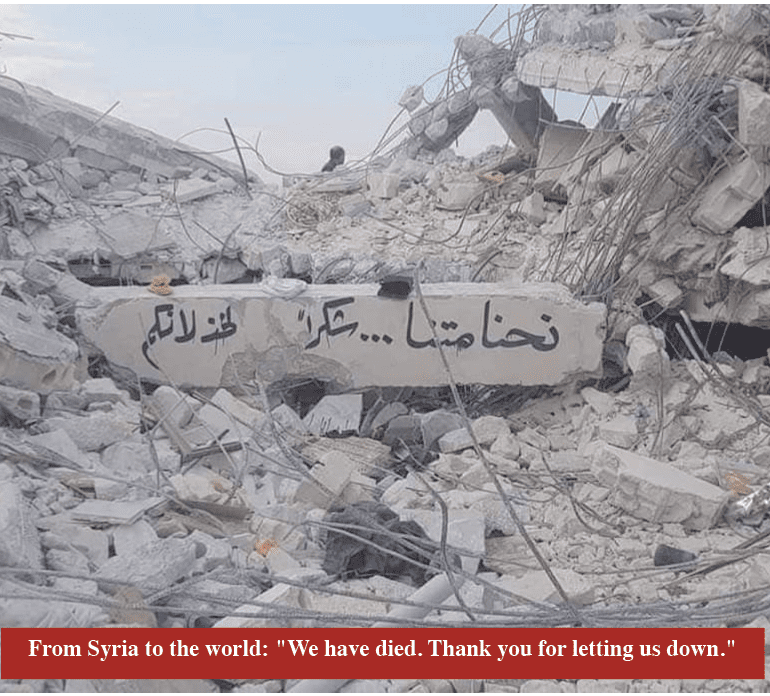

Anyone seeing suffering is involuntarily driven forward – to assist. Yet Syrians globally, those most affected by the agonizing images and stories emerging from the earthquake sites, feel both immobilized and shy behind their tears and frustrations. It’s not any threat of personal danger in a war zone that inhibits them from joining the rescue. It’s the international embargo against Syria.

Given the strict measures imposed by the U.S. and its allies on the Syrian government, even those eager to arrange help are hesitant to gather urgent support at such a critical time. This includes me, unable during the past decade to even send a gift to my close friends.

From my longtime association with Syria, and from regular talks with people residing there, I keep abreast of the toll the war and blockade are taking. I know economic and health conditions well. I know how, month after month, rising food prices mean more citizens go hungry. I know that medicines are in desperately short supply, whereas Syria was once an exporter of pharmaceuticals. I know that the rich farmland of Northeast Syria, breadbasket of the region, is under U.S. occupation, making its wheat crop inaccessible to Syrians. I know too that Syria’s oil from that same NE region is commandeered by foreign companies under U.S. military protection. I know that most young men are now outside the country; the same for doctors who may manage to find a country to use their talent and training. (Syria, once celebrated for its high medical standards, had had a surplus of doctors).

I know that no foreign exchange is permitted with Syrian banks, so that anyone wanting to send funds to a family left behind cannot do so. I know that Syrian homes have electricity for barely a few hours daily because the electricity system is in disrepair, unfixable without imported parts. I know that Lebanon, which had been helping thousands of Syrian families, can hardly continue this because of its own economic collapse. Humanitarian aid from Iran too has dwindled due to its domestic problems. Whoever can leave do, risking the flight to neighboring countries, including Turkey, then venturing further afield. For over 12 years their absence has drained the nation of its professionals – writers and artists, filmmakers and pharmacists, scientists and social workers, teachers and IT experts. What is more, the country is regularly bombed by Israel.

These conditions are disturbingly and piteously similar to those ravaging Iraq throughout the 1990s, a saga I myself chronicled. That nation was shredded by years of embargo, leading up to the U.S.-led military assault and occupation in 2003.

Whether or not the destruction following the February 6 earthquake is as extensive in Syria as in Turkey is irrelevant. Urgently needed assistance to Syria is being held up or inhibited, largely by cumulative U.S. embargoes imposed during almost 20 years of its hostile policy towards the country. Algeria, one of the few nations supportive of Syria, has pledged $15 million in aid, noting that this gift is “to the brotherly Syrian people, in solidarity.” Algeria will have to overcome U.S.-created hurdles to ensure needed supplies get to Damascus. Meanwhile a United Nations aid convoy to Syria was evidently assigned only to “the rebel-held areas” (no questions raised about that!) where the much-heralded White Helmets operate. As far as we know, relief from 74 nations reportedly rushing supplies and technical assistance to Turkey might not be shared with devastated parts of Syria administered by Damascus (and thereby embargoed).

But that may change. On Thursday, February 9, the U.S. Dept. of Treasury, the agency that stringently monitors compliance with U.S. policy embargoes, announced that it would suspend some sanctions for relief that’s directed toward earthquake issues. Doubtless there will be close monitoring, with bureaucratic delays. And individuals eager to send aid directly to family or to particular charities in Damascus could face time-consuming formalities. We don’t yet know whether this temporary U.S. license permits Syria’s embassies and consulates to work with American donors to funnel relief aid to the country. And will organizations and individuals be able to transfer funds from abroad directly to Syrian banks? That is unclear, too.

Syrians have a long and unassuming tradition of charity. They also are among the most economically successful of immigrants, wherever they reside. They will, if allowed, prove, like New Jersey doctor Souheil Saba, they’re ready to join others leading aid efforts from abroad. (Although Saba will reach Damascus only by road from Beirut, after flying there via Istanbul.)

How one decides which Syrian charities will be authorized and which banks cleared to receive funds will consume precious time. Syrians and their supporters eagerly wait for instructions and clearances. Like their Turkish counterparts, they must now turn all efforts to the injured, homeless, hungry and cold survivors.

Leave a Reply