By Zeinab A. Lecanu, special to The Arab American News

From a childhood marked by loneliness and want, Wayne State President M. Roy Wilson forged an extraordinary life of accomplishment and acclaim. His accomplishments include the presidencies of four universities, dean of two medical schools and deputy director of one of the National Institutes of Health’s 27 centers and institutes.

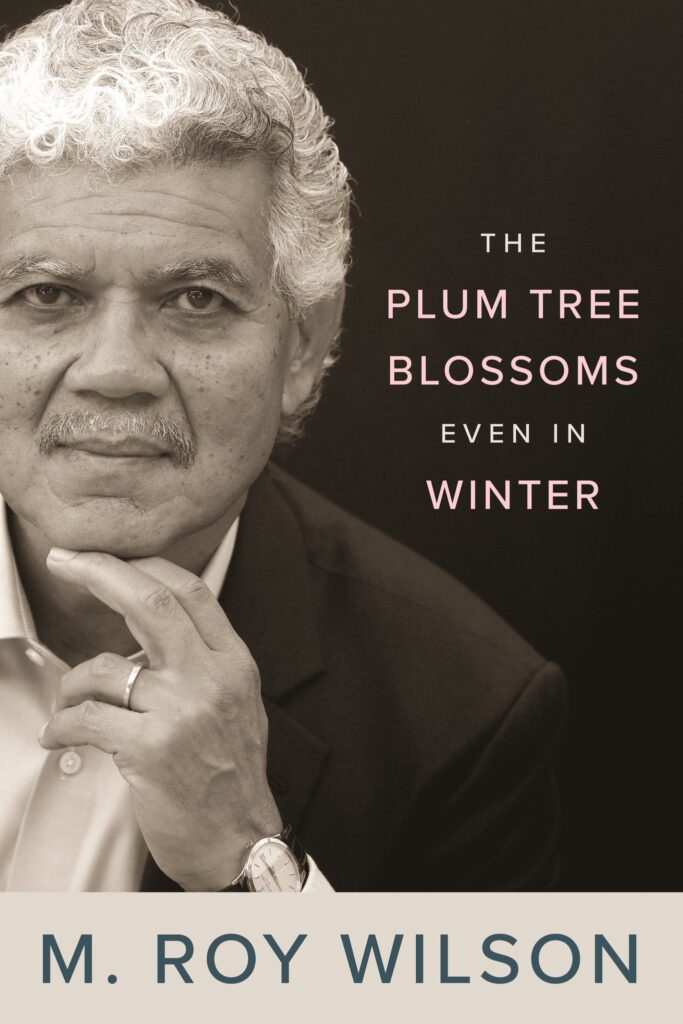

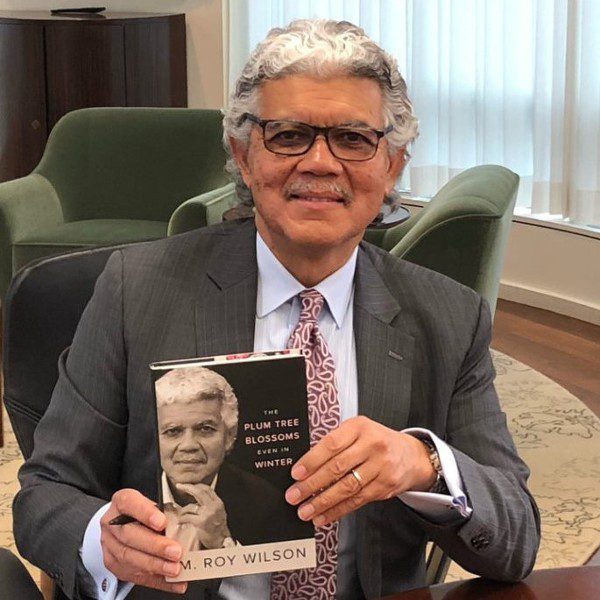

Through this inspiring and deeply personal story of struggle and success, published under the title The Plum Tree Blossoms Even in Winter, Wilson shares insights gleaned through his life experiences, many of which helped others reach their highest potentials. In his office, on a windy afternoon day, he welcomed The Arab American News to talk about his touching book.

- The title of this memoir was inspired by an early childhood memory when you attended the cherry blossom festival with your mom in Japan. You chose the symbol of plum tree because it does “bloom in the coldest, dreariest month of the year.” Have you ever wished to have a cherry tree life instead? I mean have you ever wished if you were born, let’s say, to a mainstream middle/high class American family?

It’s a good question. You know when you’re going through challenges and difficulties it’s easy to think that you want something else, but I have to say that my experiences and the challenges that I had to go through, I think, made me a better person and someone who’s able to empathize and understand others with difficulties at a much more human level, particularly as a higher education leader. So that when situations sometimes arise, where let’s say a minority student experiences something, I can personally relate to it because of my own experiences and then I handle that situation differently than a person who hasn’t had those experiences.

So I feel that ultimately I became stronger, more empathetic and more understanding of others. I will also say that I am very cognizant of the fact that there are other people who had undergone some worse situations than me; at least I had two parents and a lot of people don’t have one or both parents, so I don’t want to make it seem like my story is the worst story ever. There were some interesting aspects to it and that’s why I wrote the book.

- In chapter 3, you talk about how you rejected, as a child who lived his first years in Yokohama and later in Sayama, to be “Westernized.” But at some point in your life you had to choose your identity as a Black male; was identity a matter of choice for you? Why didn’t you align yourself with an Asian American belonging?

Two major influences I think; the first is when I left Japan and I think it’s probably first or second grade, I can’t remember that, I went to Youngstown. My dad’s family was Black and the neighborhood was all Black, so I was surrounded basically with African Americans and so unlike when I was in Japan my everyday interactions were with African Americans. That’s what I came to know, going to church with grandma.

The second part of it, when I went back to Japan and I was old enough to play basketball and be competitive. People I hang out with were the G.I.s; we were in an Air Force base that did not have a lot of Black teenagers to play with, but I didn’t really identify with people who were my age, I just hang out with the G.I.s and my identity as a Black male really became more solidified.

- Aimé Césaire, the greatest francophone poet, talks about Negritude as “not being a philosophy, neither metaphysics, nor a pretentious conception of the universe. It is a way of living history within history.” What’s your personal understanding of the African American heritage; a social/political struggle for equality? A need of unity with the Black Diaspora?

I think that as an African American, and from a historical perspective, it all goes back to slavery. I don’t think that Blacks throughout the world have the same experiences. I remember one time I was in Africa and I went to a small village that was supposed to be not a kind of a touristic place, but rather a place to see what everyday Africans do and I remember feeling being out of the place; everyone is looking at me and I am a foreigner here.

That’s when I realized that people in the United States who talk about going back to Africa and this kind of stuff, not only to visit but “to connect with their roots?” Yes, they don’t really understand how our experience here in this country is so unique that we don’t have a lot in common with the Blacks in Africa, we really don’t. It’s a very different experience. So everything as African Americans is tied up to the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow laws and all that.. All our identities are connected to that.

- Growing up in an unstable family frame, you developed survival skills at a very early age. After reading the book I am amazed how a person who endured all this suffering could possibly get to the highest social rank. You mentioned the influence of your high school teacher Ms. Stephan, who introduced you not only to a lot of books and writers but also to the Dolce Vita like French cuisine and wine. Did this special connection inspire you to be a leader in higher education?

Indirectly yes, but not directly. I think my relationship with Ms. Stephan or her biggest influence on me was that she made me feel that I was special and I had an obligation to do something to improve society; that it wasn’t enough to do something like I will make a lot of money or have a lot of fun and that I had to do something to improve society. She made me feel that I had the skills, maybe not the skills at that time, but I had the talents that were there somewhere to do so.

And so I didn’t think I was going to go (into) higher education; I didn’t go to college saying I want to go to higher ed., but as things transpired I gravitated to two areas in which I could do something to help improve society and people’s life; one is medicine and the other one is higher ed.

So indirectly I was drawn into something that has a greater social value than just going to work and getting the paycheck, living in a big house and going on vacations. I was really blessed in my career that I was able to do medicine and higher ed. How more can you wish for?

- This memoir is very touching and inspiring because you decided to talk about the positive and negative sides in your life. But talking about our personal life requires a real courage, the courage to expose vulnerability; “memories warm you from inside, but they also tear you apart” according to Haruki Murakami. President Wilson, why did you decide to not wear a mask? I mean you could “polish” a lot of events as some celebrities would do.

You know a part of the reasons of writing the book was cathartic. I thought that there was a story to be told and once I started writing it, it started coming out. You’re talking about wearing a mask, but I thought that maybe throughout my entire career I did wear a mask. Because of the way I presented myself, because of my education, my knowledge of things like wine and so forth, people have made assumptions about me. When they found out that my dad was in the military they thought he may have been an officer and I never said that. I never lied and said my dad was a general or anything like that, but I never went out of my way to correct people’s assumptions, so in a way I was always wearing a mask.

And one of the things that Wayne State has done for me, and I mentioned this in my announcement where I said that I didn’t want to renew my contract, I specifically said in there that a leader is most effective when he or she can find his or her voice and I felt that Wayne State gave me my voice and for that I am very grateful. What I meant by that is that in a lot of institutions that I led before I couldn’t be totally genuine because their values and mine didn’t totally line up.

And this is true until now; there are so many institutions, particularly in the south, where I couldn’t come out with a lot of statements like promoting diversity and things like that. I would’ve been in trouble. Here I speak truthfully and genuinely about things that are my values and know that I was also speaking for the university and that gave me the courage to be genuine and unburnished because I felt that what’s Wayne State is. It accepts all people from minorities and immigrant populations. And so in writing this I just felt comfortable in being truthful.

Initially, to be honest, I was not going to write this before I was finished with the presidency, not before I retired; I didn’t want to reveal a lot of things and I thought I would be judged. It wasn’t that I did it because I had a change in heart; I did it because I just had the time because of the pandemic. But when I started doing it I realized it was actually the right time to be able to be this exposed because it may have more impact than when I am no longer the president.

- You will be known as the president who greatly improved Wayne State by constructing the Pistons arena, renovating the students center, adopting a 10 years facilities master plan, opening the Mike Ilitch School of Business and other major projects, in addition to achieving the nation’s most-improved graduation rate—a 21-point improvement—from 2012 to 2018. How do you see the future of the university in the few coming years?

So, I was committed and passionate about what I do. You know the buildings and all that is great, but what I am probably most proud of is the improvement in the graduation rate that touches people and gives them opportunities when they finish their study.

Because of my own background, I am very passionate about higher ed. to make sure to create opportunities. My world experiences certainly made me a more effective president; I would also say that having cancer and thinking that I only had a certain time to live made me a more effective president because I treated everyone differently than before.

- President Wilson, I know you said in your book that a reporter asked you about your feelings about being the first African American leading Texas Tech. For some reason comparing you to President Obama is inevitable. Maybe it’s the dream of a post-racial society as you describe it. Do you think that America will achieve this dream one day?

Yes, I am optimistic, but I think there are challenges. In many ways racism in this country has gotten even worse; it’s more open than it was 15 years ago. Whether some of it is a reaction of having a Black American president I don’t know, but there is more open racism. Some of it has to do with President Trump, actually, so that worries me a little bit.

On the other hand, more people and more institutions are accepting the legacy of slavery and racism with more active anti-racist policies. It’s not enough just to say we should treat everybody equally, I think you have to be consciously anti-racist; and I think a few years ago this term was not very well known, but now it’s very common and there are organizations and books to talk about being anti-racists, and a number of different academies.

There is a conscious effort of being anti-racist by many organizations for the first time — as an example the better funding of Black schools. There is a lot of effort going on and I think if we want to reach a post-racial society, we’re not going to reach it by saying “I treat everybody the same, I don’t see race.” Well, that’s the problem; you have to see race and you have to treat people differently because of race and you have to confront the issues. I am optimistic but we have to work intentionally.

- Wayne State has a large number of minorities’ students; you state in your book that it’s “the most diverse university in Michigan and among the most diverse research universities in the country.” What do you say to students of color and especially Arab Americans since this interview will be published in Arabic for Arabic speakers, too?

I would say is that the strength of this university and this country is the diversity of its people and that their presence here in the university and in this country is something that makes this country the greatest of the world — the idea of accepting immigrants and promoting diversity regardless of some immigration issues. We’re not like Japan, for example, an isolating country. So whatever minorities you belong to, you’re important to the fabric of this nation and you should persevere whatever the challenges are.

- My last question is that if you have the power to go back to your childhood, what would you like to tell the boy M. Roy Wilson?

That’s a good question and you know in my book I talk about the last words my mother told me: “Roy you must forgive, you must forgive!” And how I pondered what she meant by that and I think what she was getting at is that I had a lot of anger inside. And so maybe if I could tell the little Roy Wilson something it would be to let go, let go the anger. People have faults, they aren’t perfect; let go!

Leave a Reply