DETROIT — Palestinian cartoonist Mohammed Sabaaneh came to terms with his heritage as a child, which forever changed the orientation of himself and his work and shaped, from an early age, his activism.

“[When] I was 6-years-old, I asked [what was] the name of my country,” Sabaaneh said.

His mother replied, “You are from Palestine.”

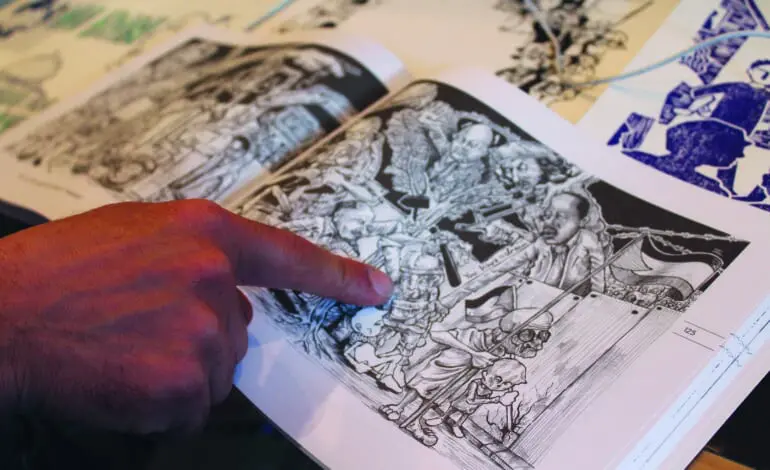

As part of his book tour, “White and Black: Political Cartoons from Palestine”, showcasing a comprehensive collection of his cartoons and artwork, Sabaaneh has visited numerous venues around the U.S. to educate and engage audience members on the decades-long plight of Palestinians under the Israeli occupation.

His Detroit presentation, before a crowd at the Bottom Line Coffeehouse, accompanied Chicago-based artist and zine-maker Leila Abdelrazaq in her discussion of her 2014 graphic novel, “Baddawi.”

Born in 1979 and raised in Kuwait, Sabaaneh completed school in Jordan, to which he moved during the first Gulf War in 1991.

There, Sabaaneh felt as if he started a “new life.”

He found work as a portrait artist and began to do portraits of Palestinian martyrs.

He attended a march during the second intifada, also known as the Al-Aqsa intifada, where he was accompanied by his friend Zacharia.

Upon arriving at the checkpoint, a frightened Sabaaneh learned that the Israeli soldier was targeting the students.

Later, on his way back from the protest march, an unwelcome surprise greeted him via a radio announcement.

“I heard from the news we learned they lost a student and they mentioned the name of my friend Zacharia,” he said.

As the severity of the Intifada intensified, the families of local martyrs began to ask the portrait artist to draw commemorative portraits of their lost ones.

A 13-year-old boy, whose brother was killed by an Israeli soldier, even asked Sabaaneh to draw his portrait should he be killed.

A 13-year-old boy, whose brother was killed by an Israeli soldier, even asked Sabaaneh to draw his portrait should he be killed.

“That question shocked me,” Sabaaneh admitted in his recollection. “Why don’t our kids have dreams or futures?”

He said he told the boy he would have a better future than his brother and would go to school and university and get an education.

It was not to be. Three weeks later, Sabaaneh learned that an Israeli soldier killed the boy, who was trying to carry out an act of vengeance for his brother.

Sabaaneh then did his portrait.

He transitioned into an editorial cartoonist for Palestinian daily newspaper al-Hayat al-Jadida, one of only three Palestinian newspapers currently in circulation.

In 2010, Sabaaneh visited the U.S. as part of a convention for the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. There, he got acquainted with many American artists, included working on a project in joint partnership with an artist who would use art and drawing to psychologically help orphaned and homeless children.

In 2013, Sabaaneh faced an arrest upon returning to Palestine from Amman. An Israeli soldier stopped him and searched his suitcases, then put him in detention.

Having made prisoners the subject of his drawings, he felt that he became “one of his cartoons.”

Moved to a detention center, he was held in a small, rough cell for three weeks. He used art as psychological support, just as he had done with the student in the U.S.

During interrogation, he stole a small paper and pencil and started to draft ideas for cartoons that he developed once he was moved out of the prison.

Drawing sketches that touched on events and themes around the world, with these sketches and themes forming the basis for his next exhibition in 2014, “Cell #28”, named after the same cell in which Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti was held.

Moving his exhibition through Spain and Jordan, he met numerous cartoonists worldwide, drawing inspiration and exchanging ideas from both the people and pieces he encountered.

Some of his cartoons, abstract depictions of crowded chaos, were inspired by artist Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica”, drawn to depict the devastating effects of Nazi rule.

“That’s why when I went back to Palestine, I did my Guernica,” he said, referring to a piece that combined the calamity and intermingling of symbols and elements with the underlying theme of catastrophe endemic to life under occupation.

Many of the Palestinian characters in his drawings, from political prisoners to civilians, are drawn without mouths. This represents how the Palestinians have been rescinded of their voice in the systemic denial of their rights.

“We have been prevented from telling our own story,” Abdelrazaq agreed, in stating the intent behind telling her father’s narrative of life in refugee camps.

The artists, like other Palestinians wielding the power of the pen as their medium of activism, agree that the steadfast expression of their culture and identity poses a threat to the Israeli occupation.

Both the artists seek to showcase the Palestinian resistance as an act of agency while giving an accurate depiction of the struggles of martyrs, activists, their families and communities.

“There was a realization,” Abdelrazaq said, “that while these stories seemed common in Palestine, there wasn’t a lot of understanding outside Palestine.”

Intertwining narrative elements with art, Sabaaneh spoke to the dual roles he’s assumed as an artist who utilizes his talent in a journalistic medium.

As his involvement in a Palestinian newspaper has shown, Sabaaneh said his job is to “report to the people what’s happening inside the Israeli jail.”

He added, “I will use my art to convey what is happening to the prisoners inside the prison to people around the world.”

Leave a Reply