SEATTLE— Palestinian American architect Rania Qawasma was planning her thesis proposal halfway through her distance learning master’s program in sustainable design at Boston Architectural College (BAC) when she realized she needed to omit her original idea after spending a day with and listening to the concerns of resettled Syrian refugees in Seattle.

SEATTLE— Palestinian American architect Rania Qawasma was planning her thesis proposal halfway through her distance learning master’s program in sustainable design at Boston Architectural College (BAC) when she realized she needed to omit her original idea after spending a day with and listening to the concerns of resettled Syrian refugees in Seattle.

Qawasma had initially thought of designing a housing complex that would accommodate refugee families, but realized that the simple details that everyday Americans disregard are essentially some of the biggest challenges these refugees face coming in.

“I know the housing development idea is a good one and it’s still in my mind,” she said. “But I needed to do something right away to ease their transition here.”

Refugees come in not knowing that the lifestyle is totally different than what they’ve experienced in the Middle East and there’s no one to explain that to them.

Qawasma had come to the realization about her thesis idea when volunteering at a picnic for refugees in August 2016. One mother told her that she’d dumped water on the kitchen and bathroom floors to clean, not knowing that there were no drains. Another woman said the smoke detector went off while she was cooking— scaring the whole family. She didn’t have the exhaust hood on.

Another family broke its garbage disposal, an appliance they’d never seen or used before.

After deep contemplation, Qawasma decided to go with what her gut was telling her and began drafting a “neighborhood guide.”

“It’s a way for them to learn about things around their neighborhood easily, in graphics, in the least amount of words,” she said.

At first, Qawasma was worried that her thesis would be viewed as unfitting in the architecture field— one that’s usually connected to structure rather than the activity within it.

“But my theory, which was supported by many professors in the department, was that architecture has the physical side to it and the other side— the operation,” she said. “When you design a building, you need an operation manual that teaches people how to use the [structure] you’ve designed.”

Qawasma’s thesis advisor, Eric Corey Freed, an architect based in Portland, also approved the plan. From there, she organized the challenges refugees face or may face along the way into nine categories. She also studied urban iconography, infographics, travel and language guides— producing the perfect transition manual called “This Is Home.”

Her book won the top BAC sustainable design award in May.

Each of the categories is designed to help the refugees adapt to the internal and external facilities available for them, Qawasma said.

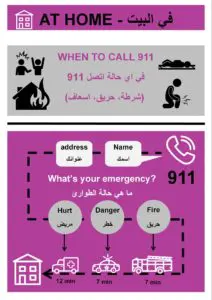

The first category, “At Home”, teaches refugees the significance of memorizing their home address and the order it’s written or said— number, street, city, state and zip code. It also describes safety measures that need to be taken inside the home, like calling 911 in certain cases of emergencies or how to carefully use the devices they’ve newly encountered.

The shopping section provides major store logos and information on the difference between each store and the products they offer.

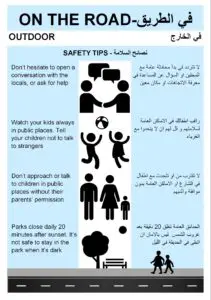

The third section, “On The Road”, explains the driver’s license application process as well as the rules and safety about all types of transportation. The finance segment teaches about debit cards, credit cards, how to open a bank account and how to write a check.

The remaining categories provide information on metric conversions, healthcare, national holidays, contacts and services.

Qawasma wrote the book in English, but with Arabic translations, so that refugees understand or catch on the new language.

She provides the book for free to them. However, if an organization orders more than 50 copies, it has to pay the publishing cost.

Qawasma customizes copies based on the states refugees live in. So far, she has sent hundreds of books to Washington, California and Maryland, and has received requests from organizations in Arizona, Minnesota and New Jersey.

The book has also been translated into Farsi, Spanish and Dari.

While she was working on it, she teamed up with a Zurich, Switzerland organization called Architecture for Refugees that inspired her to launch her own American chapter in Seattle.

“The more I talked to people here, the more I felt the urge to start my own because people want to help here, but don’t know how,” she said. “There isn’t any kind of knowledge or awareness about the refugee issues in the U.S.”

Qawasma will be serving as its founder and her first two events will take place in September at the Seattle Design Festival.

“Both workshops will be introducing the design community to refugee issues and talking to them about the different ways we can help integrate refugees into our communities,” she said.

Qawasma noted that her project started as a small entity that transformed into one that could change lives, so she encourages people to take that first step, no matter how trivial their ideas may seem at first.

Leave a Reply