“The first thing to do is establish what we actually want to do with the money, how much is needed, what issues we want to address and come up with solid plans. Those plans have to be very detailed and exact.” – Dave Mustonen, Dearborn Schools communication director

DEARBORN — As communities scramble in search of the best methods to keep their schools safe, Dearborn’s education and city officials say measures that could curb violence have always been a top priority, but they have no plans to make school buildings safer in the long-term.

Youth and officials debate course of action

There have been about 20 shootings at schools in the U.S. this year alone, but the one that sparked the most outrage and political action wasn’t the last.

After a 19-year-old former student at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida opened fire in the building shortly before the school day ended on Feb. 14, killing 17 and injuring 14 more, school administrators, law enforcement, parents and especially students across the nation have been on high alert and preparing for the worst — knowing all too well that there aren’t enough measures to stop another troubled individual with a weapon from entering a school.

In Dearborn, the school district and police have largely stood by students’ demands to ensure incidents of gun violence don’t break out at any of the district’s 30 elementary, middle and high schools, and the college it oversees.

The city’s youth made their expectations clear during a vigil held five days after and a massive walk-out staged on the one-month anniversary of the Parkland massacre. Federal, state and local officials have also participated in town hall meetings to address school safety, making clear that more guns in schools should not be part of a solution.

Funding is key

In order to make Dearborn schools more immune to a shooting and implement concrete safety measures, the district first needs the funds to update the many of the buildings’ infrastructures, according to school administrators.

Between 2020 and 2030, about a dozen of the district’s schools will turn 100-years-old, Dearborn Public School’s Communication Director Dave Mustonen told The AANews.

The district’s operations department has determined that about $160 million in maintenance and repair is needed to update the schools, including upgrades to roofs, boilers, electrical and plumbing systems, as well as installing additional cameras and securing entrances.

“School are designed differently nowadays,” Mustonen said. “Their needs are different and the way we use the buildings are different.”

However, those funds aren’t easy to come by, as residents would need to vote for a bond that may increase property taxes.

The earliest a bond could appear on a ballot is this November, but Mustonen said the school administration first needs to organize a “citizens committee” that would make recommendations based on evaluations of building conditions, which would be presented to the board of education. From there, the board would start to develop a comprehensive plan for the bond, which would require the approval of the Michigan Education Department, before it could appear on the ballot.

He added that the administration is still in the stages of sending invites to community members and organizations to form the committee.

“The first thing to do is establish what we actually want to do with the money, how much is needed, what issues we want to address and come up with solid plans,” Mustonen said. “Those plans have to be very detailed and exact.”

The last time the district upgraded security at some schools was the result of a bond that passed in 2014.

Fadwa Hammoud, a trustee on the Dearborn Board of Education, told The AANews the district does not have the funding to make the necessary changes to secure all access points for all its facilities, but she has ensured that the “infrastructure discussion is always on the table.”

She criticized a failed past initiative that would have addressed the Dearborn School District’s student overcrowding problem by constructing a new high school that would have cost around $100 million, and urged parents and administrators to prioritize issues that need immediate attention, like safety.

Making Dearborn schools safer

Money aside, the debate surrounding procedures and equipment in making school safer has become as charged as the gun rights debate itself.

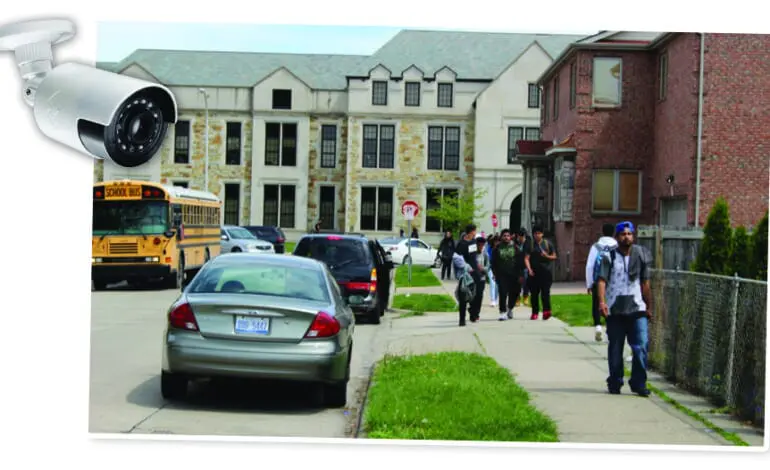

Mustonen and Hammoud said there have been talks to eventually install an enhanced camera at every entrance and hallway in every facility, some of which would be fed live to the Dearborn and Dearborn Heights police stations and to patrol vehicles nearby.

Another much-needed transformation would have visitors buzzed in at a school’s main entrance. They’d then have to pass by the main office, which would be located between a double door system.

But those initiatives have been on the district’s wish list since shortly after the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, Dearborn Schools Superintendent Glenn Maleyko told The AANews.

“We don’t have current funding to hit ideas mentioned, but we are interested in pursuing them,” he said.

Mustonen, Hammoud and Maleyko all said they would not endorse the use of barbed wire fences, metal detectors and arming teachers to keep intruders away.

“We are not the TSA [Transportation Security Administration],” Maleyko said. “There is no funding for that and we don’t want that.”

Hammoud stressed the value of investing in programs that strengthen education in the classroom, especially when teachers suffer low pay wages, and developing better teacher-student relationships.

“They are not only teachers, but counselors, bank accounts, cooks and baby sitters for students,” she said. “To add that extra responsibility to arm them is not only disturbing but outraging. The only weapons our teacher should be armed with are the books and knowledge.”

On April 12, Democrats in the Michigan House and Senate proposed a $100 million package for schools that would go toward hiring more social workers and school resources officers and upgrades for security measures like cameras and panic buttons on phones that could warn an entire school of an active shooter.

Later that week, Gov. Snyder announced a new school safety plan, which proposes $20 million to help schools upgrade security and calls for a permanent Safe Schools Commission to review plans each year.

How safe are Dearborn schools today?

Niche.com, a school and neighborhood rating platform, puts the Dearborn School District as the 36th safest (out of 552) in Michigan.

The latest shooting at a school in the city was on Jan. 26, when students from another school district fired shots at the Dearborn High School parking lot during a basketball game, but nobody was injured.

Mustonen said the school district added card-access systems in every building and devised emergency management plans about three years ago.

Maleyko said that each school, apart from the school board, has its own crisis team that meets twice a month and has been working closely together with the police to review and cooperate on emergency management protocols, which are sent to teachers.

The teams are given specific scenarios and review reenacted “table top exercises” at all buildings. Mustonen said a mock shooting is scheduled to take place at one of the schools on June 19.

The human element

Although the district might not have the funds to make every entry point secure and add more cameras, Maleyko said the district holds the human element to ensuring safety in high regard.

He said district officials mainly rely on counselors, social workers and resource officers and local community organizations to maintain deep relationships with students to prevent violence at the schools.

The district employs 36 social workers, with two more in the hiring process, who discuss and work together on cases referred to them by teachers, according to Roula Bazzi-Gates, a Dearborn Schools social worker. The training they receive includes best practices in dealing with trauma and positive behavior intervention support.

Dearborn High School, which has about 2,100 students, employs three social workers.

“We have a very big caseload and it would be great if we could add dozen or more social workers,” Mustonen said.

In addition to a couple of security guards stationed at two of the high schools, seven school resource officers— specially trained armed Dearborn police personnel— patrol the schools, thanks to a federal grant awarded to Dearborn Police three years ago.

According to Dearborn Police Chief Ron Haddad, police officers make a total of 600 to 800 unannounced visits to schools every month, a policy that began two weeks before the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting on Dec. 14, 2012 in Newtown, Conn. that left 20 dead.

Scott Casebolt, the principal at Edsel Ford High School, told The AANews safety is something he thinks about every day, especially since the Parkland shooting.

While school’s security system isn’t the most advanced, Casebolt said the schools rely heavily on the vigilance of students, staff and resource officers, and their cooperation with one another, to ensure safety.

Casebolt said staff constantly walk the halls to ensure doors are shut throughout the day and resource officers have developed close friendships with students who often point out problems or uncomfortable situations that arise with their peers, which are then referred to social workers.

He said the high school has held three lock down drills this year, underscoring to students how to react during an active shooting situation: Avoid the shooter, deny access and defend themselves.

Students have an opportunity to give feedback.

Teachers are also able to communicate their classroom’s attendance to administrators and some students have voiced the need for a deadbolt lock system on classroom doors, Casebolt added.

Kevin Caggins, a Dearborn school resource officer, told The AANews the seven resource officers, supplemented by 20 to 30 patrol officers who perform periodic checkups, are there only as a preventative measure and attested to the strong relationships they have with students.

“It’s been a very successful partnership,” Caggins said. “It’s impossible to quantify what we do, but it’s a game changer.”

Leave a Reply