DETROIT — Wayne State University’s Department of Communication presented research Tuesday Nov. 27 that examines the effects of the Trump administration on North American Muslims.

At the presentation, Dr. Stine Eckert of WSU’s journalism program introduced three doctoral candidates and contributors to the studies, Jade Metzger-Riftkin, Sydney O’Shay-Wallace and Sean Kolhoff of the Department of Communications.

Eckert, a former Al Jazeera producer, said her previous studies incited an interest in Muslim identity; and though many studies based in number-based research found how Islamophobic rhetoric causes an increase in hate crimes, she wanted research based in conversation.

“As I developed this project the Trump campaign came along,” Eckert said, “I didn’t plan for that; nobody did. It happened to be in this time that we started this research. So it kind of just fell into my lap to then ask more specifically, in this moment of heightened concern, particularly for people who claim that as part of their identity, what does that mean?”

She said the study covered the time period of the latter half of the Trump campaign, the election season, before his inauguration and into the first 100 days of his presidency.

“Arguably 2016 was a new sad peak of Islamophobia a decade after 9/11,” Eckert said. “We covered this entire time.

“We were especially asking, ‘what does that experience look like?’” she added. “When this experience happens, what do you do? And what does that look like, face-to-face and online?”

Eckert said around two thirds of participants were between the ages of 18-23, but did reach to mid-50s, and were from “many different backgrounds”, including people from Lebanon, Bosnia, Europe and many others.

“We felt we had a pretty good range of people sharing their experiences with us,” she said.

“Responses to Islamophobia were directly related to how people experienced instances of Islamophobia,” Kolhoff said of the study’s findings. “Unfortunately we had a wide array of experiences people could have, ranging from micro-aggressions all the way to blatant acts of racism.”

He said face-to-face instances of Islamophobia often featured discussion of the locations where they occurred; and people most often responded to Islamophobic situations by educating those who mistreated them and by behaving as an example of Islam.

“I could be the first Muslim they’re meeting,” a study participant said. “I could be the only Muslim they know. I need to be the best possible representation of Islam I possibly can, because there’s like one slip-up and they’re like ‘oh, all Muslims do this.’”

According to Kolhoff, participants sometimes talked about going back and educating others, trying to do what they can to change non-Muslims’ perceptions of who Muslims are.

Kolhoff said the face-to-face instances seemed to be a clear result of the 2016 election, and most were unavoidable. He said people often responded by ignoring comments.

“Overall they were situations that they couldn’t completely get away from,” he said. “They wanted to respond angrily or forcefully, but they knew if they did whoever saw that would then get a bad perception of who Muslims are.”

Metzger-Riftkin said about 75 percent of participants in the study reported “consistent” experiences of Islamophobia online.

“It was almost an inundation,” she said. “It was the frequency with which they spoke about it online.”

She also said participants reported educating, ignoring comments or avoiding certain social media platforms they thought contained more hate speech.

“But online just looks a little bit different,” she said.

According to Metzger-Riftkin, tactics that appeared online didn’t appear elsewhere.

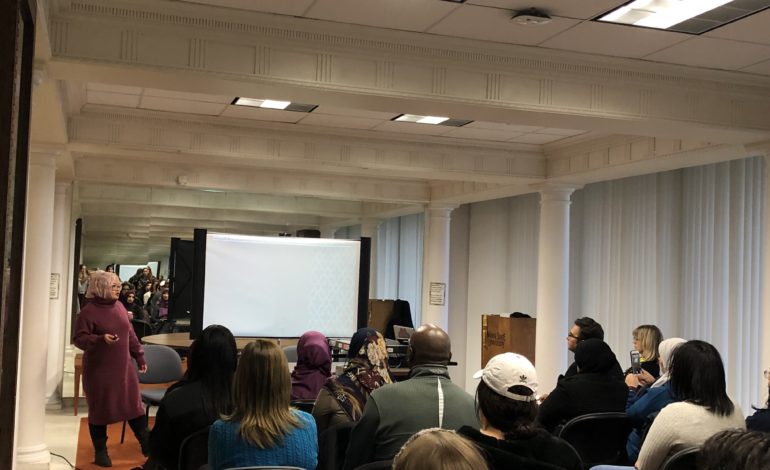

Jade Metzger-Riftkin presents study results at Wayne State University, Tuesday Nov. 27

O’Shay-Wallace, who is in the midst of writing her dissertation, shared preliminary results Tuesday of her research on Muslim identity.

“The first phase really is trying to get a broad-stroke picture of social media use within a specific minority population,” she said. “I wanted to see how exactly the Muslim population operates [compared to] the general U.S. population.”

She said first she needed to establish a base-line to find out what kind of online platforms North American Muslims use and how often. This preliminary study included 435 participants identifying as Muslim, 69.7 percent of whom were women, 30.3 percent men, with ages ranging from 18-72. Ethnic identities of participants varied, with most identifying as South Asian, 20.2 percent Arab or Middle Eastern, 16.6 percent Caucasian and 9.9 percent African American, totaling 13 different categories.

“It’s really one of the most diverse culturally, ethnically diverse populations in the U.S.,” she said.

O’Shay-Wallace said the first survey found Muslim women are less likely to engage in self-disclosure online, while converted Muslims were more likely to engage in such disclosure.

Overall, this preliminary study found Facebook was the most-reported used social media platform for Muslims at 51 percent. Participants rated Instagram as second, Twitter third and Snapchat fourth.

Leave a Reply