Being an American doesn’t mean that one should surrender his or her identity and culture. Let us be proud Arab Americans.

The Arab Spring somewhat rectified Nasser-era nostalgia that pined for a strong pan-Arab identity that complemented, rather than contradicted, the rich diversity of Arab speaking peoples.

The strong sense of self-fostered character solidified into a political identity that rejected the neocolonialism and imperialism that had threatened Arabic political agency.

Numerous scholars, including Amin Maalouf, Edward Said and Albert Hourani, gave voice to this identity in their pluralistic and scholarly articulation of a liminal and cross-cultural “Arabness.”

These intellectuals, having influenced thought and communicated their cultural perspective across media and across nations, as dual French and American nationals, gave merit and voice to the world citizen that was also— proudly— Arab.

In recent times, we have shied away from this identity in lieu of alternative titles slightly more palatable to a modern-day Orientalist social climate.

This is observable in our willful use of the designation “Middle Eastern” people, rather than “Arab.”

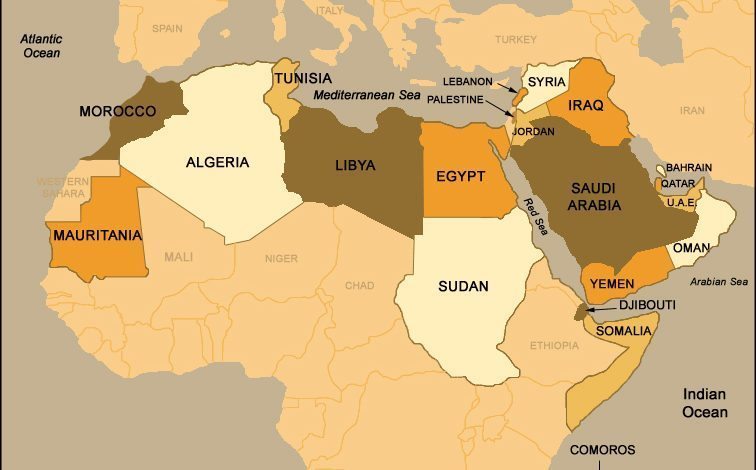

“Middle Eastern” is a regional title that includes numerous non-Arab nations, such as Iran, Turkey and Israel. Its use often dilutes and threatens the rich cultural and linguistic identity of the Arab people.

Yet numerous individuals, groups and organizations have dropped “Arab” in lieu of “Middle Eastern” or “Muslim” in their titles.

In his 1988 paper, “The Middle East, In Whose World?”, given at the Oslo conference that year, Hassan Hanafi highlights the inherent Eurocentrism of the term. He disparages the expression as a construct of old British colonialism that reinforces political power dynamics that Arab self-determinism should reject.

“The expression Middle East is an old British label based on a British Western perception of the East divided into middle or near and far, which are two relative concepts having Britain as a referring point,” he wrote, stressing the need for internally projected self determination from “its own label. It is called the Arab World.”

In a political climate muddied by sectarianism and civil strife, it is more imperative that we reaffirm and reclaim our title that speaks to the unity, while still respecting the cultural, ethnic and religious plurality, of the Arab people.

For hundreds of years throughout our history that is, unfortunately, far too often ignored, religious pluralism was the norm, not the anomaly, for people in the Arab and Muslim world.

Yet the politicization of the region in light of conflicts in the latter part of the 20th century, namely in the aftermath of the 1979 Iranian revolution, invited religion to become a primary identifier of people in the Arab world— a newfound concept of self-identity that also resonated with Arabs in the U.S.

However, just as Arabs have historically celebrated the nuances of their identities and cohabited numerous cultures and civilizations, Arabs today, while proud of their identity and history, reject self-imposed isolationism in their ongoing pursuit of establishing networks of solidarity and support with members of all different ethnic backgrounds and groups.

They stand with numerous other cultures to comprise the rich American mosaic that finds its beauty in its distinct and pronounced multiplicities.

The United States is a mosaic of nationalities, cultures, religions and creeds, not one homogeneous people. Being an American doesn’t mean that one should surrender his or her identity and culture. Let us be proud Arab Americans.

Leave a Reply