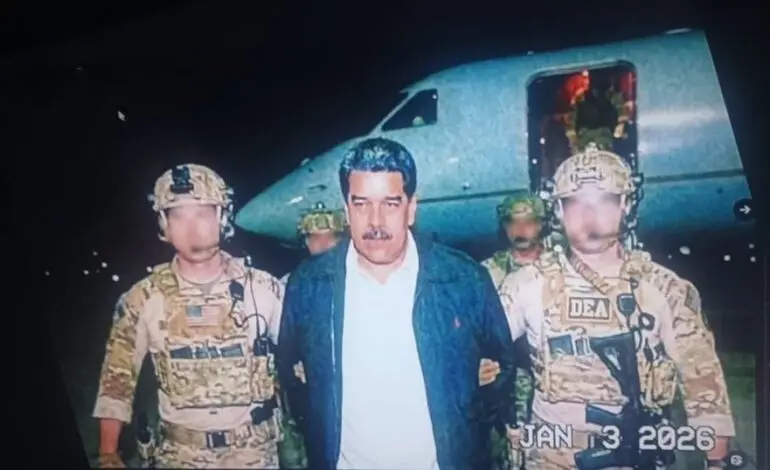

President Trump might be popping corks, toasting “one of the most stunning, effective and powerful displays of American military might and competence in American history.” Celebrations, however, are premature. In reality, the assault on Venezuela and kidnapping and transfer of President Maduro to stand trial in U.S. court are by no means a victory. On closer scrutiny, more questions than answers are apparent.

Several issues must be considered.

The deadly U.S. military attack and kidnapping rings the death knell for the structures of international law and diplomacy created in the aftermath of the two world wars.

The disturbing lesson is that powerful nations can impose their will and get away with it. This has long been understood by Israel which, with U.S. blessing, has been committing murder and mayhem and imposing its will on its neighbors with impunity. Other nations may now decide to follow suit, rendering obsolete the United Nations, international courts and international law.

The deadly U.S. military attack and kidnapping rings the death knell for the structures of international law and diplomacy created in the aftermath of the two world wars.

On the domestic political front, the president has unilaterally committed the U.S. military to attack another country without congressional authorization, as is required by the U.S. Constitution. Such approval wouldn’t make the actions in Venezuela legitimate, but without notifying Congress Trump’s actions are doubly egregious. The administration’s argument that this isn’t a war, but enforcement of a criminal indictment, is rendered bogus after weeks of bombing Venezuelan ships and positioning a naval armada to enforce a blockade.

President Trump isn’t the first U.S. leader to act in contravention of international law. But previous presidents have couched their actions with high-minded rhetoric to mask their aggressive intent. Trump has outrageously and straightforwardly stated his imperialist goals, while he and members of his cabinet use threatening language more suited to gangland bosses than leaders of a democratic nation.

Without pretense of restoring democracy to the country, the president made clear that the U.S. has acted to “take back” Venezuelan oil facilities, nationalized a decade and a half ago. Recently seized oil tankers, he claims, will be used to repay the U.S. for lost oil revenues. The president declared that “we will run the country” and that the newly installed interim president “will do what we want” or face a fate worse than Maduro.

A murkiness clouds the entire undertaking. What’s the end game? The president says that the U.S. will run the country until it’s fixed — presumably meaning after U.S. oil companies control the country’s vast oil resources with the Venezuelan government acting like a client state.

Trump will need to either dig in deeper, putting his leadership at risk, or do what he has done before, announce victory, change course and/or create a new crisis to distract attention from yet another failed policy gambit.

The early smooth-going of this misadventure may not last. Venezuela has governing institutions and Maduro’s party has control over the military and a sizable militant armed support base. How does the U.S. seek to impose its will on these structures that are ideologically opposed to American domination? So far, threats of more U.S. military strikes and/or of violence against government figures to force compliance are the only proposals.

Without committing U.S. troops over an extended period of time, accomplishing compliance is unlikely. This raises the final question: Will the president be able to sustain U.S. public support for this entire affair? If Venezuelan resistance emerges, the answer is most likely “No.”

Some analysts have compared the Venezuelan affair to Iraq. Comparisons can be made, but only to a point. For example, when the U.S. first invaded Iraq, President Bush had support from both Democrats and Republicans. The Bush administration had been making the case for a connection between Iraq and Al Qaeda’s 9/11 terrorist attacks. They argued that deposing Saddam and establishing a friendly government could be done in a few months, requiring only a limited deployment of U.S. troops, and little cost, with Iraqi oil covering the war’s costs. That, of course, was not the case. As the war dragged on with rising casualties and costs, public support eroded.

In the case of Venezuela, polls show that initial U.S. public opinion is already divided on the administration’s actions, with only 40 percent in support and 42 percent opposed. While there is a deep partisan split, independents are two-to-one opposed. Should it become necessary to station U.S. troops in the country, or should there be casualties — American and Venezuelan — opposition will undoubtedly grow. Then the president will need to confront nervous congressional Republicans who will see disaster in the polls. He will need to either dig in deeper, putting his leadership at risk, or do what he has done before — announce victory, change course and/or create a new crisis to distract attention from yet another failed policy gambit.

– Dr. James Zogby is the founder and president of the Washington based of the Arab American Institute (AAI)

Leave a Reply