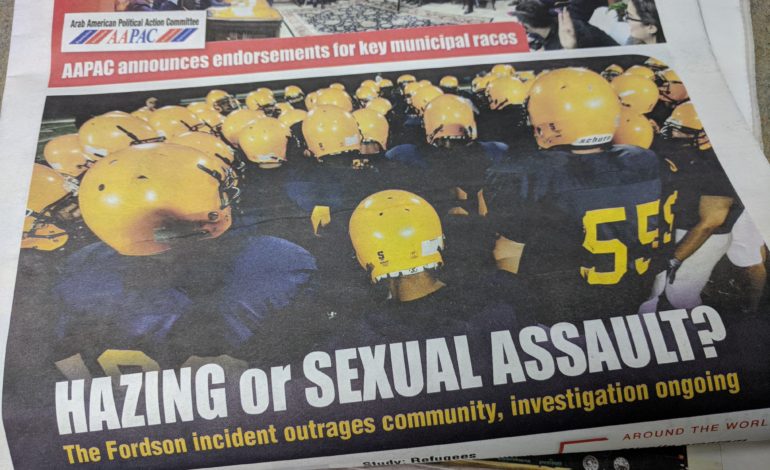

The Fordson High School football team caused an uproar after making headlines two weeks ago when a few of its junior varsity players were busted in an alleged hazing scandal that some students argue was a sexual assault.

The administration called it a “rogue hazing” incident and Superintendent Dr. Glenn Maleyko confirmed that it was not rape.

He said in a blog post that the stories are all rumors and inaccurate.

“I can confirm it was not an incident of rape,” he said. “These were students involved in behaviors that we will not tolerate in this district.”

Soon after, students and parents gathered to protest outside Fordson High School.

But did they ask themselves what they were protesting for? Were they protesting the quick measures taken by administration or the investigation itself?

The district, in collaboration with police, is doing its job— to determine the truth. Therefore, instead of using mere rumors to assess the incident, residents should be patient. Once the investigation is complete, they can protest all they want— it’s their right and our right as a community to know the truth and protect our children. Whether it’s hazing or sexual assault, it’s an intolerable act that needs to be dealt with and to be labeled properly.

According to a study conducted by YouGov, an international Internet-based market research and data analytics firm, one in five Americans undergoes hazing in high school.

Earlier this year, the Associated Press uncovered about 17,000 official reports of sexual assault that spanned a recent four-year-period by students in grades K-12— boys making up the majority of participants and victims.

That means the incident at Fordson, whatever it may be, is not an isolated one, but rather a norm that we as a community need to put an end to in our schools. What better way to do so than through educative programs and through the insight of professionals who have studied similar cases and treated them?

We published an article last week titled, “The Fordson incident: Hazing or sexual assault? While school district, community and police look for answers, here are some professional perspectives.” Some residents felt it magnified the issue because it discussed in detail reasons for and outcomes of acts of hazing and sexual assaults in schools, from sociological and psychological perspectives. It also asked if our institutions, parents and the community are doing enough.

That’s not exaggerated, but rather interpretive reporting— which other than facts, offers context, analysis and the possible outcomes.

Critics need to understand that the incident had already become an issue when the school informed the public, when police got involved, when social media user spread stories and rumors, when students and parents gathered to protest outside Fordson High School soon after news broke and when the district— according to last week’s article— found a need to “coordinate sessions with some university athletic programs that have dealt with these types of incidents” to educate students further and stop potential episodes from happening.

Regardless of the reasons listed, it is an issue that must be displayed front and center because a student got hurt by other students in our own community. When one member is harmed, the whole community should stand up for him or her and should not sweep an inexcusable act under the rug or try to play it down.

The main point of the article, which is clearly evident when read, was to raise awareness— not to tarnish a culture or school district’s reputation.

Sociology Ph.D. candidate Salam Aboulhassan said in last week’s article, “You ignore it by protecting [the institution]. You’re led to believe that because of this one incident, now the whole school has a reputation and is a bad school, when that’s not the case.”

This is exactly what the critics are doing, instead of dissociating an incident done by an individual or two from an ethnicity, culture, religion, community or an institution. They fail to treat it as an individual act and want to silence a victim or potential victims for that reason.

As Aboulhassan and longtime psychologist Dr. Hoda Amine said in the article, undoing mentalities that silence a child for cultural protection, supporting him or her and raising awareness starts in a family setting before a community and its institutions.

“Parents need to talk to children about how power works, because they have very little control over themselves,” Aboulhassan said. “…There needs to be clear conversations within families about if someone treats you inappropriately that you shouldn’t fear speaking out.”

“They have to love their children unconditionally,” Amine said. “They have to let them know that it is not their fault and that they can face it together— it [shouldn’t be] the world and them against their child.”

This is the only way to get past this incident— learn from it, strengthen the victim and any possible victims, teach the perpetrators a lesson and call for community action.

What’s important is not a name or reputation, but rather the end result— our children’s safety.

Leave a Reply