DEARBORN — Rabih (Rob) Darwiche had a childhood similar to many other east Dearborn kids. He was 6-years-old when his family moved here from Lebanon in 1989. He lived like any other kid and went to McDonald Elementary and from there to Lowrey.

Though Darwiche had a perfectly ordinary childhood, being the youngest of his seven siblings, and had a loving, Muslim family, he would go on to suffer from drug addiction from his teenage years to his early 30s, a scourge that has led to great tragedy for far too many families in his town, the state and the country.

He was 12 the first time he had come across marijuana and was 15 when he first used. The cozy, insecurity-numbing euphoria of that first time led to continued use, unbeknownst to his family. This kicked off what Darwiche called “my Career in Lying” because the more consuming his habit became, the more he had to lie to conceal it, for the end goal of sustaining his drug use without any hindrance.

He was into sports and played football in high school, but the marijuana affected him to where he didn’t play his junior year. He was also looked at differently by his teammates and was alienated.

This was only the beginning. Soon, an opiate dependency came into the picture.

Fix to fix

Darwiche injured his knee playing basketball at age 19 and took Vodocin for the pain. His body developed tolerance to the drug, meaning once his prescription was no longer available, he suffered from withdrawal.

“Once I got off the drug, I thought I had the flu, but it turned out to be withdrawal,” he said.

The irony is that he was prescribed further drugs, specifically Suboxone, to deal with the withdrawal and its physical discomforts. But once all those prescriptions were cut off, he, not even 20-years-old at the time, went through 65 days of withdrawal. For comparison, heroin usually has 12 days of withdrawal.

The restlessness, insomnia, anxiety and the never-ending flu-like symptoms of his withdrawal steered him toward illegal street drugs. By this time, he needed the substances, not for any pleasure whatsoever, but to ward off pain and to keep his drug-tolerant physiology at normal functioning levels.

I have 22 nephews and nieces, and I was the warning, the black sheep of the family. But I was also addicted to escape. It was my Career in Lying.

“Now there’s little to no pleasure in consuming the drug. It’s never the same as the first high,” Darwiche said. “Everything after this is what we (the recovery community) call ‘chasing the dragon.’”

He dropped out of school, went from job to job and had nothing going for him. The addiction proved to be a mental disease and wrought a collapsed self-esteem, crippling social anxiety and loneliness that broke him down in heart and soul. There was no hiding the problems that piled up and his family had long figured out his struggle anyway.

“I have 22 nephews and nieces, and I was the warning, the black sheep of the family,” Darwiche said. “But I was also addicted to escape. It was my Career in Lying.”

Lying to his family, to himself, running away from the problem. Darwiche lived hopelessly from fix to fix, unable to come out of a self-feeding disease that took his twenties away from him. There were times of relief, such as when his family decided to send him back to Lebanon. It was a chance to get away and —for a moment — it did look like he would finally recover.

“Over there, I even had an operation done on my teeth,” Darwiche recalled. “All that smoking, and the addict’s bad hygiene, ruined my teeth. When I came back home, my sister was like ‘hey, look, you’re okay now.”

But after returning to the same environment where his addiction had taken root, it wasn’t long until Darwiche would relapse. He chased the dragon; lied; escaped. He overdosed four times by the time he was in his early thirties. He moved between detox centers, jail, then back to the same environment, over and over again.

“I was a frequent flyer, is what it’s called,” he said.

A long road to recovery

Darwiche described how unforgettable it was when one day he returned home from the detox center.

“I remember sitting in my room with cigarette burns on my skin, on my pants, on my bed.”

And on May 3, 2016, at the age of 33, potentially facing nine years in prison, with a suspended license, possible kidney failure and a damaged liver, Darwiche surrendered. He moved into a three-quarter recovery house on July 8.

“The first night the power was out,” he said. “The beds in the rooms upstairs had bugs. It was 98 degrees. We were 14 men trying to sleep in a small living room.”

But his time there was short-lived. He got into a fight with a roommate and ended up on the streets, homeless.

To come out and admit his powerlessness over his drug problem – the first and most important of the 12 steps – was Darwiche’s turning point and brought better things along the way. He met Ali Sayed, the founder of Hype Athletics and its subsidiary SAFE Substance Abuse Coalition, from whom Darwiche got a custodial job.

“The very bottom of Hype’s totem pole,” as put it.

His late father had dementia at the time and had mobile impairment and incontinence. Scrubbing public toilets opportunely gave him the strength and humility to help his dying father.

“There was perspective in the job,” Darwiche said. “It also made me think of my mom ,who cleaned up after us every day. I would become the greatest toilet scrubber if I had to.”

It was about being given the chance to build up again, to recover both his health and the relationships he had lost to his substance abuse.

During one of his job shifts, Darwiche happened to stumble upon $150 and there it was: An invitation to chase the dragon: “But no. I called up my boss and told him about the money.”

This would officially be Darwiche’s retirement from his “Career of Lying.”

“I ended up giving away the money,” he said. “It was my first donation.”

Staying clean

Darwiche endured and stayed clean. Eventually, he was even offered the opportunity to make his own drug interventions. It was becoming time for him to gift recovery to others because, as he says, “to keep what we have, we give it to somebody else.”

Newcomers to recovery are both the hope and reminder for the substance-clean that recovery is always possible, but so is relapse and return. It is a process that never ends and must constantly be struggled and strived for. Addicts aren’t recovered per se, but recovering.

And Darwiche has been recovering for six years. The office at Hype Athletics he was interviewed in for this article was the same office he was interviewed in for his janitorial position. He sat on the opposite side of the desk.

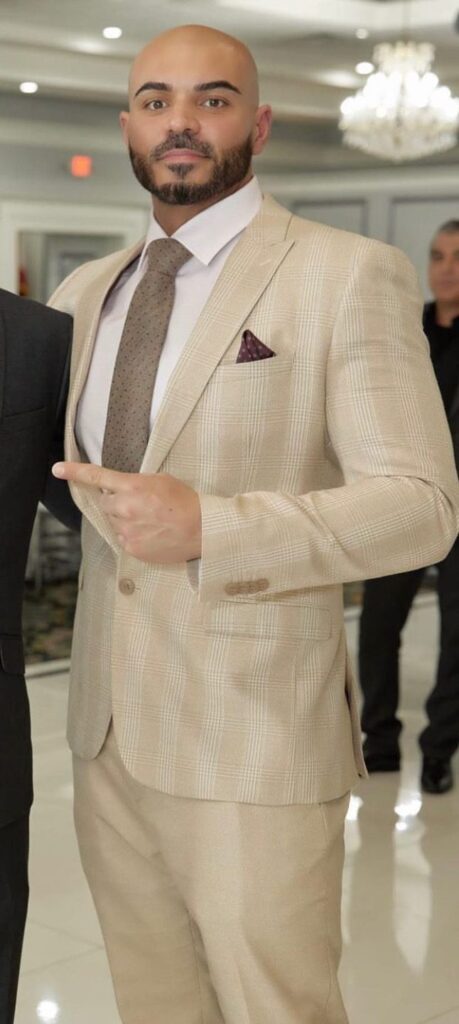

He has an infectious positivity. He narrated his experiences with great eloquence. With his golden bald head, well-groomed peppered beard, marble-white teeth and jacked upper body, you’d think he had never touched any kind of drug. When he was addicted, he couldn’t comprehend never using, but now he can’t comprehend ever using.

On the desk was his folder filled with old water-damaged papers. These are all his signature forms for treatment centers, court papers and other documents relating to his drug history. On one of these were about a dozen names in blue sharpie with their phone numbers. Darwiche knew these individuals. They also had drug issues. Only some are still alive.

It’s all part of the bigger game. Teaching these kids to stick together and watch out for each other. Addiction is a disease that does not discriminate and can afflict anyone.

On the off-chance that someone with a drug problem reads this and is willing to take the first step, Darwiche has something to say:

“Pick up the phone like I did then, call the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority for detox and residential treatment. If you have private insurance, turn your insurance card around and call the number. Then after, call me if you want. Maybe we can have coffee together and speak recovery for a better way of living. Do not feel any guilt, shame. You’re loved. We love you.”

Darwiche gave a speech at the Islamic Center of America for Ashura awhile ago. He read:

“Today I am spiritually fit. My passion is in helping others and serving. I have my driver’s license, have no felony, no ticket in six years. Hamdulillah. I am the general manager at Hype Athletics in Wayne. I’m also the director of operations at SAFE. A life coach, a personal trainer, peer recovery coach and have facilitated 200 drug interventions. Right now, I am running for City Council in Wayne.”

Darwiche said he believes the most important form of intervention is to begin with youth. There is a reason why SAFE Substance Abuse Coalition works under Hype Athletics youth programs.

“It’s all part of the bigger game,” Darwiche said. “Teaching these kids to stick together and watch out for each other. Addiction is a disease that does not discriminate and can afflict anyone. I am telling my story and my experience, so it can be a lesson for others, so that they don’t have to suffer the same consequences.”

—Hassan Abbas contributed to this article.

Leave a Reply